On April 23 at 9:09 p.m. local time, residents of Aguas Zarcas, a small town in Costa Rica, saw a large “fireball” in the sky.

The reported fireball was a meteor about the size of a washing machine. As it entered Earth’s atmosphere, it broke apart and rained hundreds of meteorites in and around the small town, including a two-pound rock that crashed through the roof of a local house, smashing the dining room table below.

While meteorite falls happen around the world on a regular basis, early reports indicated that this meteorite belongs to a special group called "carbonaceous chondrites" that are rich in organic compounds and full of water.

“Many carbonaceous chondrites are mud balls that are between 80 and 95% clay,” said Laurence Garvie, a research professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration and a curator for Arizona State University's Center for Meteorite Studies. “Clays are important because water is an integral part of their structure.”

From these early reports, the race was on to collect samples and bring them back to labs around the world for scientific analysis.

“These had to be collected quickly and before they got rained on,” Garvie explained. “Because they are mostly clay, as soon as these types of meteorites get wet, they fall apart.”

Fortunately, meteorite collectors had five rain-free days in the region to collect samples from the fall. About 55 pounds of meteorites (collectively the size of a large beach ball) have been recovered so far.

As of last week, ASU has acquired several meteorite samples from the Aguas Zarcas fall, which were donated by meteorite collector Michael Farmer. Farmer traveled to Costa Rica immediately after the meteorite fall to purchase and collect the meteorites from residents of Aguas Zarcas. A private donor has also provided funds for ASU to purchase additional meteorite samples from this fall.

ASU leads classification of Aguas Zarcas meteorite fall

Once Garvie had the donated samples, he rushed back to the lab on ASU’s Tempe campus to run the analyses needed to determine the classification of the meteorites. He is now leading an international classification effort.

“I was in the lab by 5 a.m. the next morning after picking up the samples to get them ready for the initial analyses,” Garvie said. “Classification of new meteorites can be like a race with other institutions, and I needed ASU to be first so that we’ll have the recognition of being the collection that holds and curates the type specimen material.”

ASU’s Center for Meteorite Studies has a specialized curatorial facility for meteorites, one that rivals many other international facilities. In particular, ASU has nitrogen cabinets for storage of particularly air-sensitive meteorites where the nitrogen atmosphere preserves the meteorites and stops their degradation.

“If you left this carbonaceous chondrite in the air, it would lose some of its extraterrestrial affinities,” Garvie explained. “These meteorites have to be curated in a way that they can be used for current and future research, and we have that ability here at ASU.”

For the meteorite classification process, Garvie is working with Karen Ziegler from the Institute of Meteoritics at the University of New Mexico. In her lab, Ziegler analyzed the samples for their oxygen isotopes, which helps determine what characteristics this meteorite shares with other carbonaceous chondrites.

Garvie is also working with ASU School of Molecular Sciences’ Professor Emerita Sandra Pizzarello, an organic chemist known for her work with carbonaceous chondrite meteorites. Pizzarello’s analysis is helping to determine the organic inventory of the sample, which may provide insights into whether these types of meteorites provided the ingredients for the origins of life on Earth.

Ultimately, the meteorites will be approved, classified and named by the Meteoritical Society’s nomenclature committee, an international team of 12 scientists who approve all new classified meteorites. This approval is the first and most important step of an in-depth scientific analysis.

Nature has said, 'Here you are!'

Because of their water-rich composition, carbonaceous chondrites can provide insights into how we may be able to extract water from asteroids in space as a resource beyond Earth.

“Having this meteorite in our lab gives us the ability, with further analysis, to ultimately develop technologies to extract water from asteroids in space,” Garvie said.

Garvie and his team, as well as scientists around the world, will be analyzing these meteorites — for years to come — for new insights about water extraction from meteorites as well as insights into the origins of the solar system and the organic process.

“Nature has said ‘here you are,’ and now we have to be smart enough to tease apart the individual components and understand what they are telling us,” Garvie said.

Carbonaceous chondrites

The Costa Rican meteorite comes from an asteroid that was an early planet (planetesimal) that had water and organic materials. “It formed in an environment free of life, then was preserved in the cold and vacuum of space for 4.56 billion years, and then dropped in Costa Rica last week,” Garvie explained.

By happenstance, the last carbonaceous chondrites meteorite fall of this significance happened 50 years ago in 1969 and was curated by another ASU professor and founding director of ASU’s Center for Meteorite Studies, Carleton Moore, who is now an ASU emeritus Regents’ Professor. The meteorite fell to Earth near Murchison, Australia, in 1969 and is one of the most studied meteorites in the world.

"Carbonaceous chondrites are relatively rare among meteorites but are some of the most sought-after by researchers because they contain the best-preserved clues to the origin of the solar system,” center Director Meenakshi Wadhwa said. “This new meteorite represents one of the most scientifically significant additions to our wonderful collection in recent years.”

The other ASU connection with this recent Costa Rican meteorite fall is that the samples closely resemble what scientists are discovering on the OSIRIS-REx mission to the asteroid Bennu, on which ASU has the Phil Christensen-designed Thermal Emissions Spectrometer (OTES). This instrument is making mineral and temperature maps of the asteroid Bennu, which is thought to be composed of a remnant carbonaceous chondrite planetesimal.

Sample on display and open to the public at ASU

Samples from this meteorite fall, and many others, are on display for the public on the ASU Tempe campus in the Center for Meteorite Studies collection on the second floor of the Interdisciplinary Science and Technology Building IV.

ASU’s Center for Meteorite Studies is home to the world’s largest university-based meteorite collection, with over 40,000 individual specimens representing more than 2,100 distinct meteorite falls and finds. The collection is actively used for geological, planetary and space science research at ASU and throughout the world.

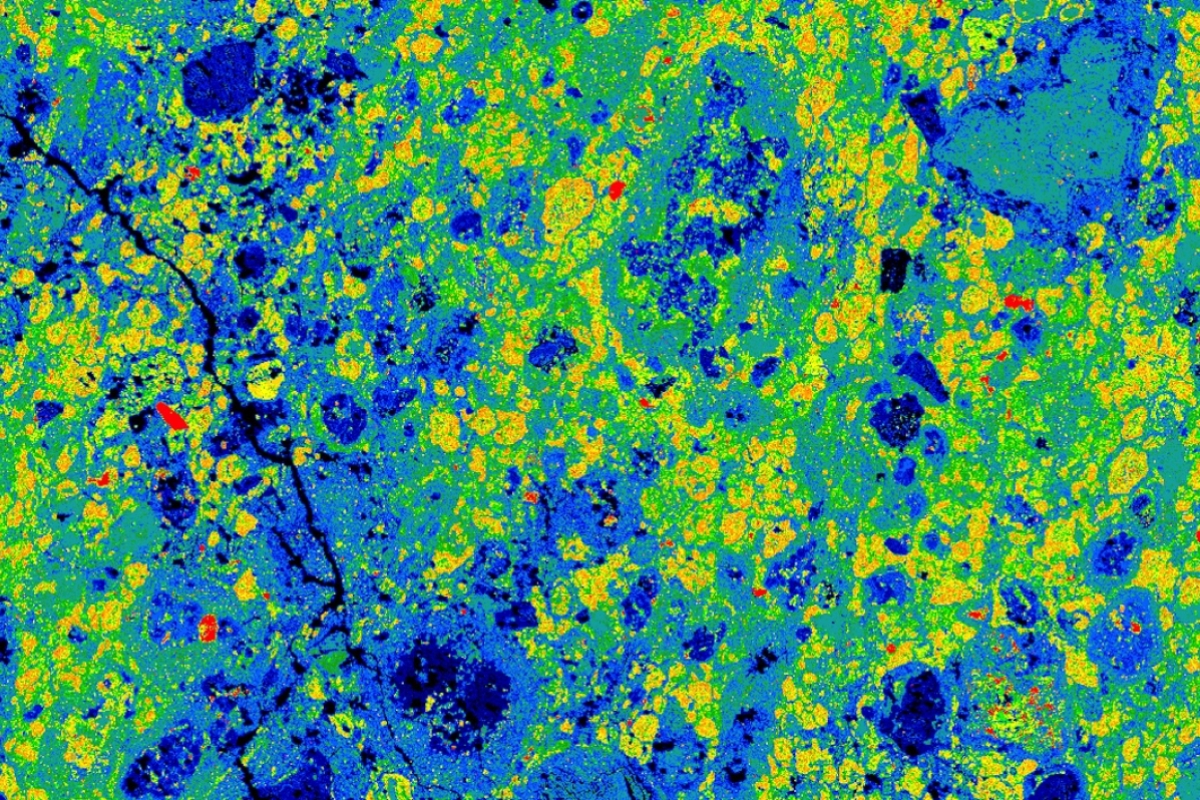

Top image: Aguas Zarcas meteorite samples, donated to ASU’s Center for Meteorite Studies by private collector, Michael Farmer. Photo courtesy of ASU

More Science and technology

Hack like you 'meme' it

What do pepperoni pizza, cat memes and an online dojo have in common?It turns out, these are all essential elements of a great cybersecurity hacking competition.And experts at Arizona State…

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive — under pressure.One such innovation is the newly released tomato variety…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper fish. Nearby, children chase bubbles and move to music, while…