ASU’s beloved late albino rattlesnake Hector left a lasting impression

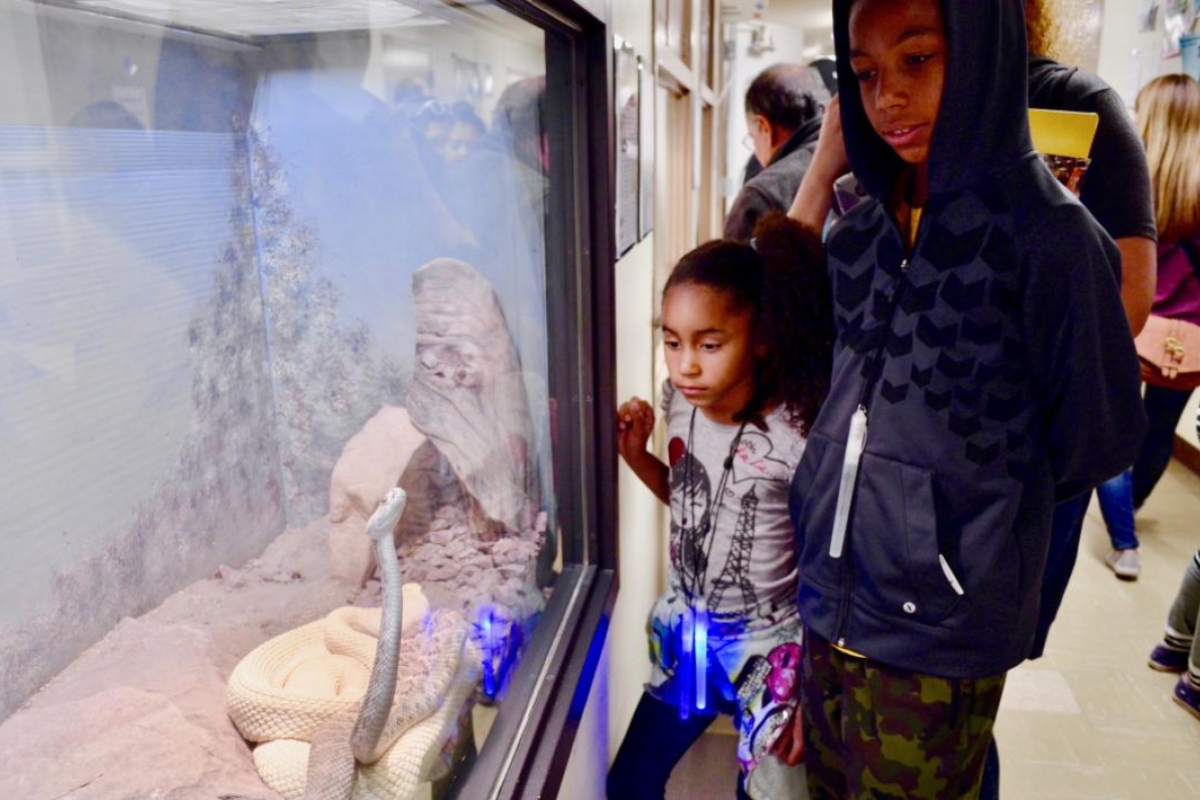

Beloved ASU Western diamondback Hector died at the age of 25. Photo by Brooks Zapusek/ASU

Sparky may be Arizona State University’s mascot, but the face that sticks in the minds of many students, both past and present, is that of an albino Western diamondback rattlesnake named Hector.

Hector was humanely euthanized this month after he stopped eating. School of Life Sciences Associate Professor Dale Denardo, attending veterinarian and director of the Animal Care and Use program, found a mass on Hector’s side. He was estimated to be 25 years old.

His loss has prompted an outpouring of grief from former students who have been sending emails and even flowers to the animal care team.

“I’ll bump into people who haven’t been to ASU in years, and they’ll say, hey, do you still have that big albino rattlesnake? Certain things last,” Denardo said. “He was an ambassador. He represented ASU and had a positive impact, not just to students going through school, but also to people who visit the university.”

Hector was one of the first showcase snakes in the Life Sciences Building A displays 24 years ago, arriving as a subadult in 1995 before most current students were even born. Because of his size — nearly a foot longer than the largest Arizona Western diamondbacks — and his unique coloration, Hector has been a conversation piece for generations of ASU students.

“To most people, a rattlesnake is a rattlesnake. They always recognize Hector though because he’s an albino,” said Sandra Schenone, who served as Animal Care and Use supervisor for 10 years. “During Night of the Open Door, I would have people bringing their kids up to me, saying he was here when they graduated. There’s that connection too. Because he was here for so long and he was distinct, they knew that was him.”

Arrival of an ambassador

Bert Allen “B.A.” Naholowa’a found Hector in the desert near Tonopah and brought him to ASU in 1995. Though they can be found in western Texas, Hector was the only albino Western diamondback in Arizona.

The first call Hector’s collector made was to the Phoenix Zoo. However, they didn’t believe he actually had an Arizona albino rattlesnake. ASU decided to at least take a look and immediately agreed to care for Hector.

Hector became a favorite of students because he adapted well to captivity, always calm in the cage.

“Even though he was larger and handling him was more difficult because of that, we were very lucky because he was an easy-to-work-with snake. He was calm,” said Sarah Hurd-Rindy, assistant director of vivarium personnel, who handled Hector for seven years. “Some snakes will snap and slide off. He was always calm and well-behaved, so it made him easy to work with.”

Because of his size, not all animal care staff were allowed to handle Hector. Once when Schenone was training new handlers, Hector got off the hook and crawled behind his cage lid. Everyone started to panic — except Hector. He didn’t rattle or strike and sat behind the lid, calmly waiting to be collected again.

Video compilation by Samantha Lloyd/ASU VisLab

“He was such a unique snake. He really stood out to everyone,” Hurd-Rindy said. “He had a such calm demeanor. When we train people to work with the snakes, they have to start with the smaller, easier snakes and work their way up, so it was also a professional goal to get approved to work with Hector and say ‘I handled that snake.’”

What’s in a name?

Hector was also unique in that he was given a name. At the time, he was the only snake on display to have one, and the only one to have a name displayed on his cage. No one knows the exact origin of Hector’s name since he arrived at ASU before any of the current animal care staff, but they think it came from the person who brought him in.

With his naming, a tradition was born that has carried on to his offspring.

About 10 years ago, Denardo realized the genes of the only Arizona albino Western diamondback should carry on. They bred him with a female, producing an offspring that had the typical black and brown coloration, but carried the genes for albinism. Staff named this snake Lucy after the Beatles hit “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.”

When she was old enough, they bred her back with Hector, a match in which each offspring had a 50% chance of being albino. The first mating produced one offspring, an albino. An ASU naming contest was held and the winning name was Bianca, the Spanish word for white.

However, Bianca died unexpectedly when she was only two.

Another mating produced three offspring, all albino.

Denardo, who hesitates to give names to the animals, told his staff that if they named these offspring, it needed to be after the rock band the Ramones. Denardo is such a fan that he has a poster hanging in his office hallway. He meant it as a joke.

The next day, he arrived at work to find the snakes were named Joey, Johnny and Dee Dee. Johnny was donated to the Phoenix Zoo, but staff hopes that Joey will grow to a similar size as Hector and take over as the face of the Life Sciences display.

An ambassador lives on

According to Denardo, Hector’s legacy is not just that he is a memorable snake. Instead, it’s what he contributed to snake conservation.

Many people fear rattlesnakes, but being exposed to one with such a calm demeanor has changed minds.

“Many students tell me that when they first got here, they couldn’t even walk through the building. They’d have to walk outside to get from one side to the other,” Denardo said. “Now, they can walk through. They’ve gotten used to it. They haven’t fallen in love with rattlesnakes, but they’re not inherently afraid and assume danger. I truly believe that the thousands of people going there each semester, seeing those snakes, does impact them.”

Denardo recalls growing up, spending his days playing outside and gaining an appreciation for nature. Without that, he says, he may not have become a biologist.

However, technology is more readily accessible today, reducing the time many people spend outdoors. Forming a connection with a snake like Hector can really influence how people view rattlesnakes, an animal which typically causes fear from those who encounter it.

“When I tell people I’m a biologist at ASU, they bring up that display. And it’s not just from last year, it’s from a few years ago,” Denardo said. “I think it promotes a connection with nature, especially a connection with something people see no value in. Some people really get attached. So, he’s done a lot. He was an ambassador. And hopefully his son or daughter will do that.”

More Science and technology

ASU water polo player defends the goal — and our data

Marie Rudasics is the last line of defense.Six players advance across the pool with a single objective in mind: making sure that…

Diagnosing data corruption

You are in your doctor’s office for your annual physical and you notice the change. This year, your doctor no longer has your…

Large-scale study reveals true impact of ASU VR lab on science education

Students at Arizona State University love the Dreamscape Learn virtual reality biology experiences, and the intense engagement it…