Cindi SturtzSreetharan was driving her daughter home from school when her daughter asked, “Do you think my thighs look fat?” The child was 9 years old.

Some moms would have found this interaction heart-wrenching and disconcerting. This was not the case for SturtzSreetharan. As a linguistic anthropologist at Arizona State University, she studies the ways people use language to construct culture and meaning. She knew that questions like, “Do I look fat?” are a common conversation engagement strategy called “fat talk.”

Her daughter could have picked it up anywhere. Here sat not an insecure fourth-grader, but a representation of a cultural norm.

SturtzSreetharan’s research in ASU’s Center for Global Health aims to understand how body weight influences our physical, emotional, cultural and social lives. Findings from her latest study were published in the Journal of Sociolinguistics on April 11.

Worries about bodies and weight affect people of every gender, race, class and age in the U.S. How people engage in fat talk and other conversations about weight could significantly impact how they respond and participate in their own social lives, neighborhoods and communities.

What is fat talk?

Fat talk is defined as self-deprecating talk about one’s body to others. Mimi Nichter, a sociocultural anthropologist from the University of Arizona, coined the term in the 1990s.

“Does this make me look fat?” shows up in conversation much like “How are you?” Both questions have a seemingly preprogrammed cultural response, in that there are set ways to respond that people just know. If someone asks you how you are, you are most likely to say, “Fine.” If someone asks whether an outfit makes them look fat, you are inclined to say “No,” regardless of what you are thinking.

SturtzSreetharan’s latest publication focuses on fat talk in Arizona, specifically the Tempe community. However, the research team also collected data from around the world, finding that fat talk exchanges occur throughout America and across the globe.

How — and how often — this exchange occurs without conscious thought is both fascinating and potentially alarming.

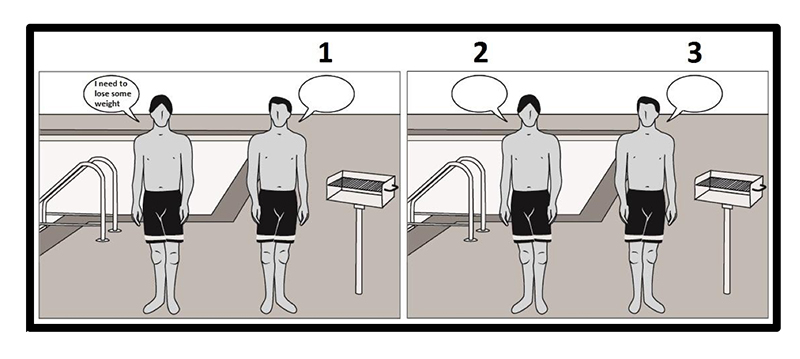

Line drawing of men with BMI 25 outside at a pool party in swim trunks. Line drawing courtesy of Cindi SturtzSreetharan

Words and culture

Culture and language are connected — they are in constant dialogue with one another. Linguistic anthropology is the study of the interactions, motivations and intentions associated with language and their effects on culture and society.

The field originated in North America, where many experts remain concentrated. Initially, linguistic anthropologists studied indigenous languages in the U.S. to highlight that studying a culture without knowing its language would yield a less accurate understanding of the human condition and human behavior.

“Linguistic anthropology is important because language is a resource humans have that they think that they completely understand and control,” SturtzSreetharan said. “They think they know what they’re doing. From my perspective, language is like a hot potato that is actually very difficult to control across receivers, across audiences and even across producers.”

Learning to appreciate the nuances of language can help inspire compassion, SturtzSreetharan said. These linguistic exchanges can allow us to dive deeper into culture and enhance our understanding of how humans interact.

Translating fat talk

SturtzSreetharan is the only linguistic anthropologist in ASU’s School of Human Evolution and Social Change. She was drawn to ASU by its interdisciplinary approach, which provides a unique space to discuss how we talk about weight and obesity, combining the perspectives of health science, linguistics and cultural studies.

“It struck me that the ways stigma is felt and expressed with regard to issues of weight and large bodies mimics the ways in which people feel and express stigma with regard to language,” she said.

ASU students work with the researchers, collecting and processing data from within the U.S. and abroad. Brian Suchowierski, an undergraduate student working on global fat talk, says he gained a new perspective.

“People often say that everyone shares insecurities across the board no matter who they are, what they are, how old they are, and I think (this research) kind of shines light on that. It might happen less frequently at certain ages, but everyone shares these same anxieties and issues, and they all talk about it in similar ways,” he says.

Hayley Trickey, another undergraduate student involved in the project, says she enjoyed working with community members. She says higher education can be inaccessible to some people. Going into the community and involving them in projects allows people to see what ASU brings to the state.

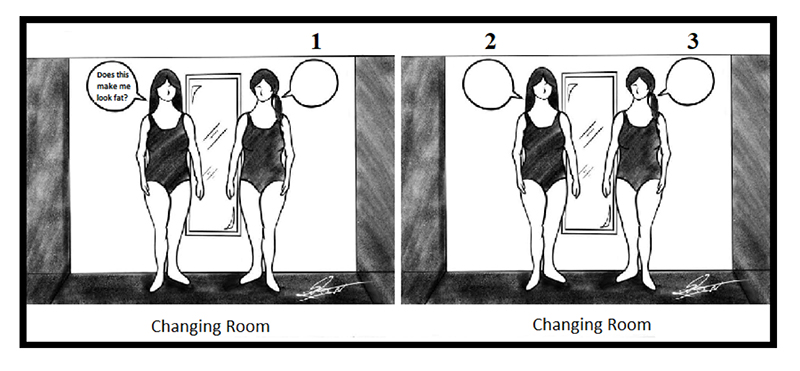

The ASU research team asked women to fill in the speech balloons in a fitting-room conversation. Line drawing courtesy of Cindi SturtzSreetharan

Two women walk into a fitting room

The team began their research by surveying adult women in Arizona about a line drawing of women trying on bathing suits in a fitting room. The drawing used the Stunkard figuring scale, a scale of people's body sizes correlated to a body mass index (BMI).

The women were drawn to illustrate a BMI of 25. A doctor would encourage a patient at this BMI to remain the same weight, but not gain any more.

In the survey, there are speech bubbles for both women. The first says “Does this make me look fat?” and the other is blank to prompt the respondent to enter an answer. Then the same two women appear in a second frame, allowing for another interaction.

The most common response was, “You look fine.” If there was a negative response, it was commonly stated as “Maybe you should try a different color.” American women seemed to share an understanding that they were not supposed to say the other woman looked fat.

The researchers also surveyed men with a male line drawing and a similar prompt. They found that while denial was the most common response among women, advice and validation were more common among men.

They piloted this study in Arizona, then sent it to Japan, Korea, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Guatemala, Iceland and Paraguay.

“What we learned by this was in some ways not surprising. We learned that the normative script overwhelmingly is to say, ‘No, you don’t look fat — you look fine’ or something like that everywhere around the world,” SturtzSreetharan said.

“It’s fascinating but also potentially concerning that fat talk is globalizing. There’s a lot of literature that suggests that fat talk is potentially psychologically damaging. But we really don’t know if that applies outside of the U.S.,” said Alexandra Brewis Slade, a President’s Professor in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change and a collaborator on the project.

She notes that the increasingly globalized fat talk seems to align with a growing lack of empathy toward large bodies and an expectation for everyone to look acceptably thin. She explains that the response to people asking if they look fat is automatically “no” because socially, the answer cannot be “yes” without being hurtful.

Most experts say that fat talk is bad because it lowers self-esteem and body satisfaction. But SturtzSreetharan believes that fat talk is more complicated than that.

“On some level that may be how we gain support and build our networks, and that may be how we make sure we feel comfort with the people we’re around. So, I think it's also this balance where these conversations don't necessarily have to be shut down, but the awareness that these kinds of conversations are everywhere is important,” she said.

Indeed, she and her colleagues find that in the U.S., people show keen sensitivity to the other speaker’s feelings when engaging in fat talk.

Understanding fat talk

The importance for SturtzSreetharan lies not in changing this cultural norm, but in understanding the interaction.

SturtzSreetharan says if you don’t talk about baseball, the weather or politics, you can just talk about fat and bodies.

“On some level, I’m not rejecting the literature that finds that it can make somebody's body satisfaction plummet or decrease, but I also think that as an interaction, it may be doing a few other things. And that is what I think we're really interested in here — figuring out, what does this interaction do? And this isn’t just about fat per se, but we also do this with our aging bodies as well,” she said.

Ultimately, SturtzSreetharan simply doesn’t want her kids to have to think about their weight all of the time. She wants to instill ways to negotiate fat talk scenarios without sacrificing self-esteem or body satisfaction. She says she hopes to teach her daughters how to think through these conversations and join in without assigning guilt or shame.

Fat talk research was funded by the Virginia G. Piper Charitable Trust.

Written by Madison Arnold.

Top photo: Student research assistants code data for the “Fat talk: A citizen sociolinguistic approach” project. Photo by Cindi SturtzSreetharan

More Health and medicine

Creepy-crawly science that matters

Written by Douglas C. TowneWhen Karen Clark was a child traveling with her grandfather, the late ASU Professor Herbert L. Stahnke, she didn’t realize how unusual their evening routines were.“When we…

A new heart

Written by Daniel Oberhaus, ’15 BAEach year, around 1.3 million children are born with congenital heart disorders, malformations that can include missing chambers or misplaced vessels. It’s the most…

Beyond weight loss: Examining the social effects of GLP-1 medications

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, more commonly known as GLP-1 medications, have become ubiquitous in public discourse, with widespread focus on their weight-loss effects.But beyond changes…