Shawn served three years in prison for burglary, then walked out to face a dizzying array of requirements he had to fulfill with almost no help and no money. He had to pay for drug testing and probation but wouldn’t get his disability check for another week, and his landlord was demanding a $50 deposit right away.

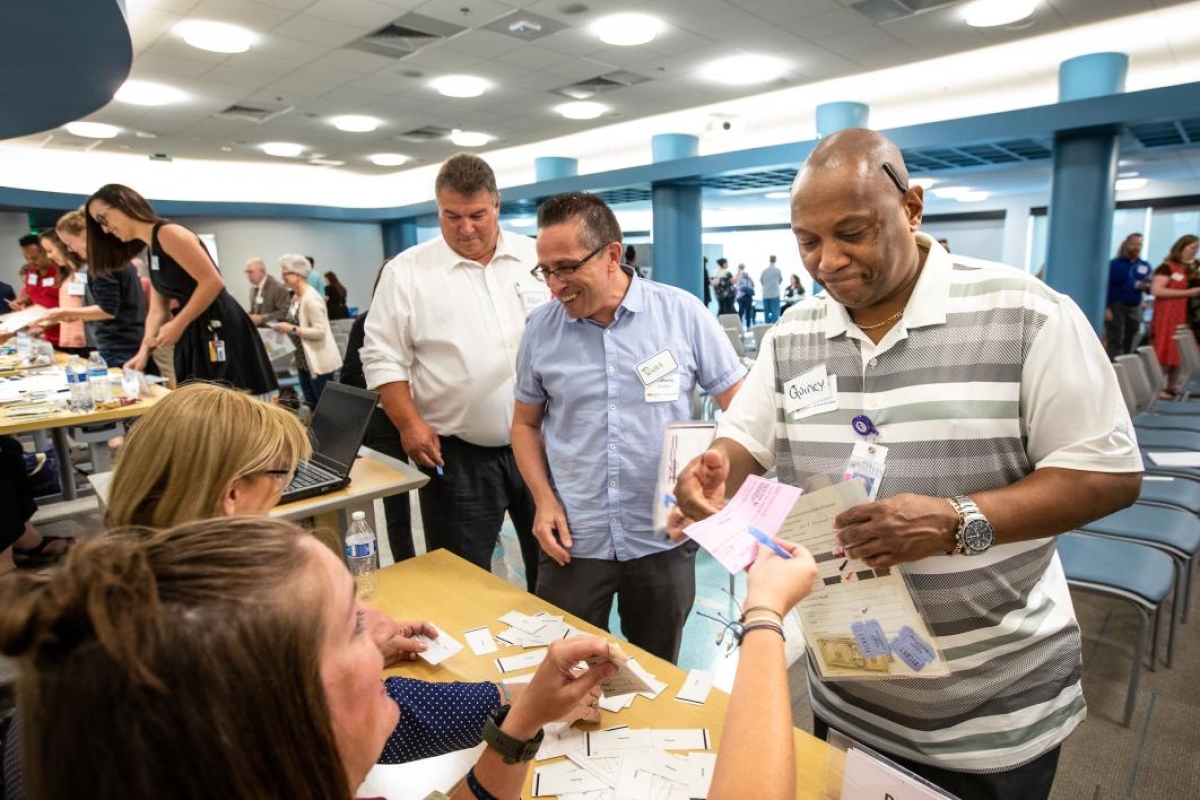

“Shawn” was one of the characters in a role-playing scenario held Tuesday by the Center for Child Well Being at Arizona State University. About 100 people participated in the “reentry simulation,” each assuming the identity of someone who was recently released from prison. The participants included students, staff, faculty and community members, each of whom received a packet describing their character’s prison record, living and employment situations and everything he or she needed to accomplish every week to avoid being sent back to jail: look for a job, undergo drug testing, pay restitution, pay rent, pay child support, buy food, attend Alcoholics Anonymous.

The simulation was put on by the U.S. attorney’s office and was based on input from real people who have been released from prison. The goal is to demonstrate what it’s like for men and women to make their way through the system.

“We release people back into their communities every day, and with very little instruction,” said Tasha Aikens, a reentry specialist for the U.S. attorney’s office in Arizona, who runs the simulation for any group that requests it.

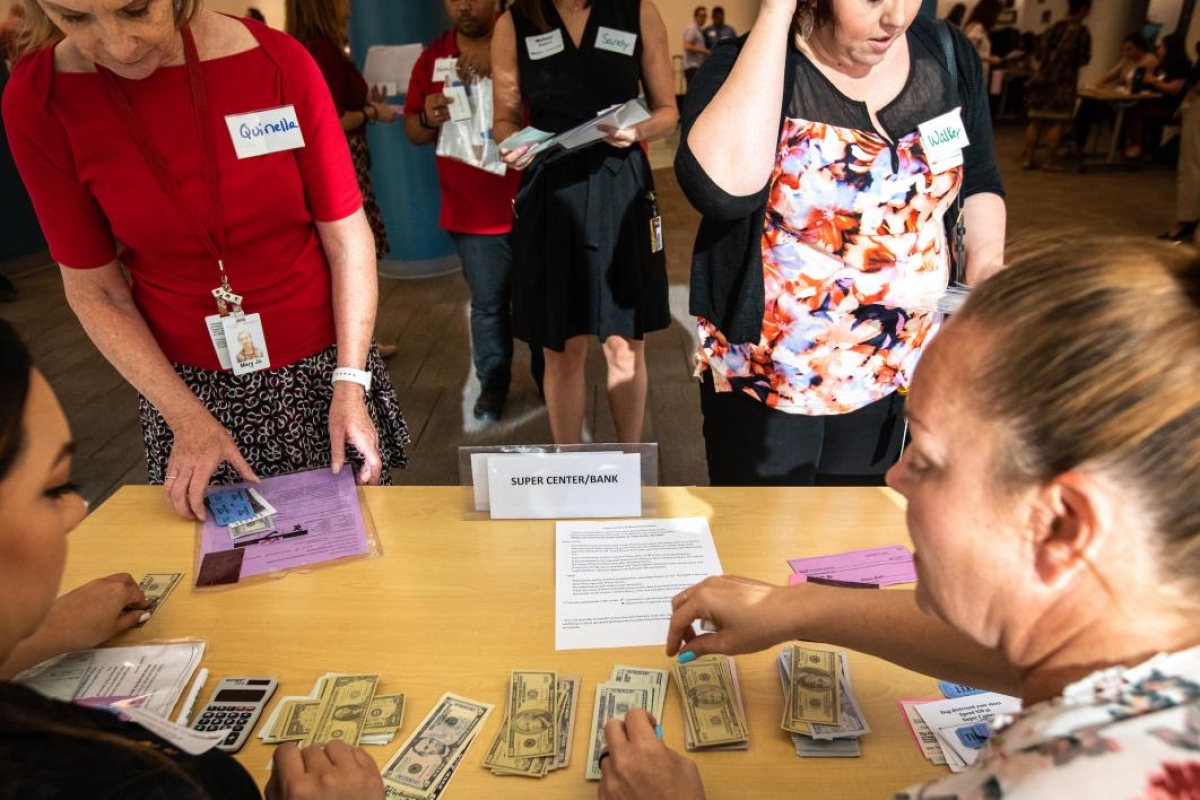

The simulation was divided into 15-minute segments, each representing one week. The room had 15 stations, representing the obligations of a returning citizen — probation, social services, bank, landlord, etc. Every participant had several tasks to complete each week.

The responsibilities were confusing and overwhelming. Every obligation required a bus pass. Even bus passes could not be purchased without handing over a bus pass.

The first week, Shawn, one of the lucky ones who left prison with $20, was able to purchase the all-important state ID card for $15, then sell his plasma for $25 to pay his $30 probation fee. He went to the “court,” handed over a bus pass and was told he needed to cash his plasma check before paying the fee. So he used another bus pass to go to the bank and cash the check and then another bus pass to finally pay the fee.

The second week was more stressful. Shawn had to wait in the church line to borrow a bus pass, which he used to buy more bus passes, then go back to the church to repay the bus pass before going to collect his disability check.

The simulation included real-life scenarios. Everyone who took a drug test had to pull a card from a deck to tell them whether it was “clean” or not. Every week, the participants received a card with an unplanned situation — like Shawn’s landlord discovering that he had a dog and needed to pay a $50 deposit.

In the third week, Shawn was waiting in line to pay his rent when the sheriff came by, saw that Shawn had not completed his second-week drug testing and sent him back to jail.

In the guided discussion after the simulation, many of the participants described how out of control they felt.

“A lot of it is pretty demeaning,” said Anthony Evans, a senior researcher for the L. William Seidman Research Institute in the W. P. Carey School of Business. The institute is working with Televerde, a call center operator that has been a leader in employing prisoners and people who have left prison. Evans said he decided to experience the simulation to gain insight into what Televerde’s workforce is facing.

“People in positions of authority should be encouraged to attend one of these,” he said.

The process was eye-opening even for practitioners. Molly Hahn-Floyd, a doctoral student at Northern Arizona University who works in adolescent behavioral health, said that during the simulation, she didn’t go to the church or social services or any other place that offered help.

“And I don’t know how many times I’ve preached to people, ‘Ask for help,’” she said.

Jan Wethers, reentry coordinator for the Arizona Department of Corrections, portrayed the mean pawn shop owner, who gave Shawn $10 for a $50 CD player.

“Take the bus sometime,” she told the practitioners. “See what it’s like when it’s hot and you have kids in tow and grocery bags.”

Empathy is critical, but so is responsibility, she said.

“You must hold them accountable. That is very, very important,” she said.

Many participants described how returning to jail felt inevitable — and almost a relief.

“If you’re released to a community and your family wants nothing to do with you and you have no job and no home and you have all these obligations, it makes sense to go back,” Aikens said. “They know your name in jail. You have food in jail. I get it.”

For a person who’s newly released, thinking about returning to prison can be a “comfort zone,” according to Theron Denman Jr., who left prison a year ago. He volunteered at the simulation “treatment” table and addressed the participants during the discussion.

“I was scared to drive, I was scared of the police, I was scared of technology,” he said. “If I hadn’t had the support of my family over this past year, I would’ve wanted to go back.

“But that’s not my comfort zone anymore. Volunteering here today is a beautiful thing.”

In the fourth week, Shawn got out of jail, bought bus passes, got food, completed weekly treatment, paid for a drug test and checked in with his vocational rehabilitation case worker. All the boxes were checked.

But it didn’t matter. While he was in jail during Week 3, he missed paying rent. Shawn was homeless.

The reentry simulation was a kickoff to the National Children of Incarcerated Parents Conference to be held next week by the Center for Child Well Being, part of the School of Social Work. The conference will include some events that are open to the public. On Sunday, the opening reception will feature photographer Isadora Kosofsky, who documents prison visitations between parents and children. Additionally, Denali Tiller, director of “Tre |Maison |Dasan” will screen her film and discuss the three young boys featured. On Tuesday, Rudy Valdez, director of HBO's “The Sentence,” will screen his documentary and discuss the effects of incarceration on his nieces. A panel discussion will follow, featuring people who have been affected by incarceration.

Top image: Tasha Aikens, a reentry specialist with the U.S. attorney's office, led a "reentry simulation" Tuesday at the Westward Ho in downtown Phoenix. About 100 students, staff, faculty and community members participated in the workshop, in which they took on the persona of someone who recently left prison and had to navigate all the tasks necessary to avoid being sent back to jail, such as getting a job, being drug tested and paying rent. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

More Health and medicine

College of Health Solutions alumnus named Military Medic of the Year

By Keri Hensley and Kimberly LinnJonathan Lu has looked out for the health of his fellow military service members his whole career, starting with his role as a combat medic in the U.S. Army.Driven by…

ASU, Mayo Clinic forge new health innovation program

Arizona State University is on a mission to drive innovations that will help people lead healthier lives and empower health care professionals to develop novel new health solutions. As part of that…

Innovative, fast-moving ventures emerge from Mayo Clinic and ASU summer residency program

By Georgann YaraIn a batting cage transformed into a custom pitching lab, tricked out with the latest in sports technology, Charles Leddon and his Mayo Clinic research teammates scrutinize the…