Cactus garden plants new ideas for understanding cancer

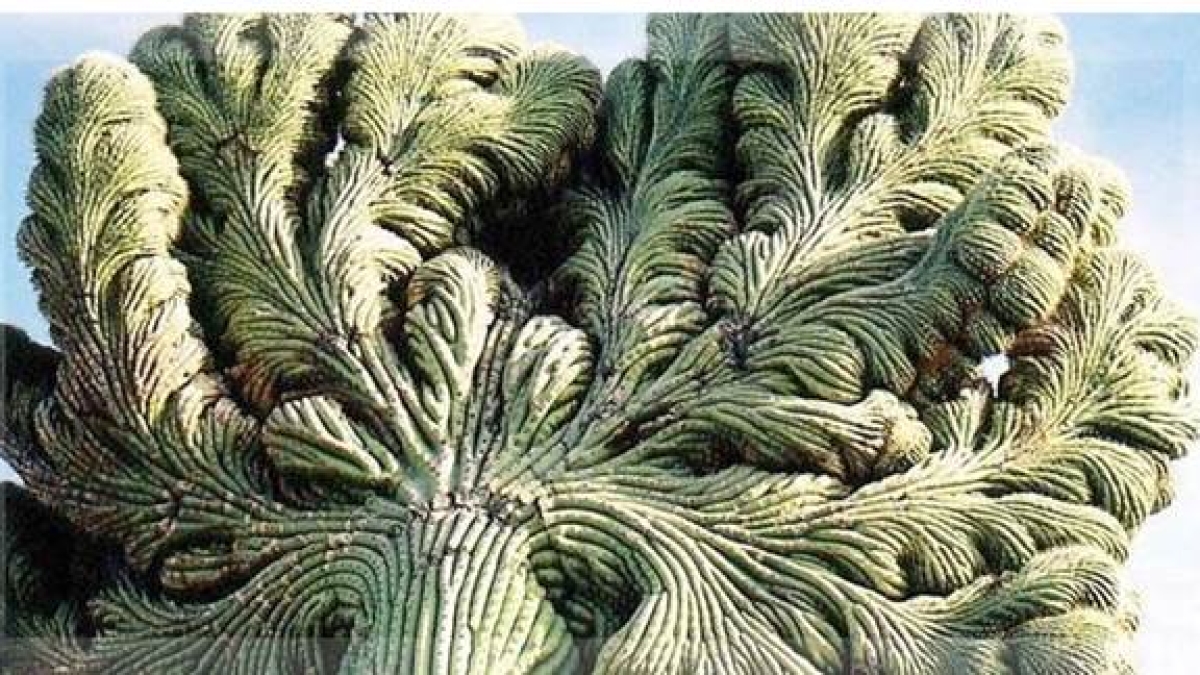

The ASU Biodesign Institute cancer cactus garden features an array of crested cacti.

When Kevin Moore joined the cancer garden project team at Arizona State University, he was dealing with stomach cancer.

“From the very beginning, I had this idea that cancer isn’t something I need to fight or have to try to beat. It’s a natural thing..." Moore said. "Part of my body went rogue, and I had to learn to live with it."

A landscape architect from Tempe, Arizona, Moore is now free of cancer.

On Wednesday, March 27, Moore gathered with a legion of cancer survivors, researchers and the curious between the buildings that make up the Biodesign Institute to celebrate the completion of phase one of the garden.

The garden features an array of crested cacti. During a visit to Arizona nearly a decade ago, Athena Aktipis became curious about the unusual growth patterns and how and why they occurred. An evolutionary biologist and an assistant professor at the Department of Psychology at ASU, Aktipis became interested in both the scientific and the spiritual possibilities inherent in Arizona’s native flora.

Caspian Robertson, an internationally recognized garden designer and director of Caspian Gardens in Surrey, England, jumped right into the desert landscape. Moore and his partner, Greg Swick, escorted Robertson to local nurseries, where he was able to select the plants. Todd Briggs and Beth Johannessen of Trueform, a Phoenix-based landscape architecture studio, helped realize Robertson’s design.

The cacti’s odd, sculptural shapes are a result of genetic changes that occur during cell division, some of the same processes that create cancer in humans. Traditional treatments rely on killing the cancer rather than contending with it.

Reviewing years and years of research, Aktipis and scientific collaborator Carlo Maley began asking, if plants and animals can live with cancer — even thrive — why can’t humans? Thus began a search through the tree of life to gain new insight in the lessons that might be applied across species to reduce the scourge of cancer.

In November 2018, the National Cancer Institute awarded ASU $8.5 million over five years to establish the Arizona Cancer Evolution Center (ACE), located at ASU, which is now a hub for an international league of intrepid explorers who are turning traditional cancer research upside down. Maley is the center director, and Aktipis is part of a team studying organismal evolution and cancer defenses.

Aktipis launched the evening event at the garden with a talk: “From Cacti to Coral: Cancer is a Part of Life.” Essentially, her message is that every multicellular creature is a candidate for cancer, and many plants and animals grow and survive in the face of cell mutations.

Aktipis combines her knowledge of biology with her research on human generosity and cooperation and conflict to characterize the behavior of the rogue cells, calling it “cellular cheating.” She observes that cheating occurs across all forms of life, defining cheating as “breaking shared rules, leading to a fitness advantage for the rule violator,” and in the case of cancer, death and destruction for the cooperating cells.

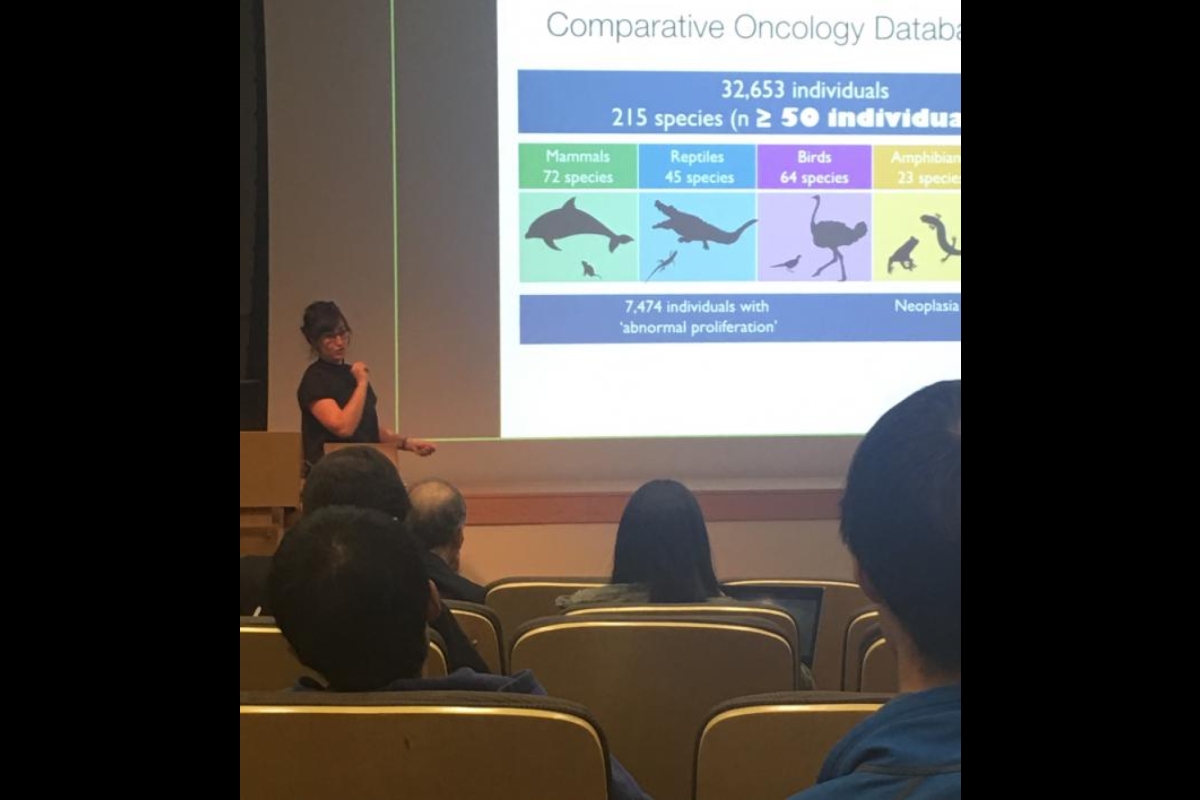

Aktipis’ former trainee and Biodesign postdoctoral fellow, Amy Boddy, now an assistant professor at University of California, Santa Barbara, is leading the ACE team in curating a database with thousands of records of cancer characteristics across species. This allows them to look for patterns, variations and insights that might provide clues as to how humans can live better with cancer.

Aktipis explained that one might surmise that the larger the animal and the longer its life, the more opportunities for cell misbehavior there would be. But this is not actually the pattern that they see — instead some larger animals, like elephants and whales, seem to have lower cancer rates than their smaller counterparts. Maley discovered why: He found that elephants have 40 copies of TP53, a cancer suppression gene. Humans have two copies of TP53, one from each parent. Newsweek featured Maley’s work in an article titled "Why Elephants Don’t Get Cancer – and What That Means for Humans."

Today, the Arizona Cancer Evolution Center is studying more than 180,000 multicellular creatures, including birds, primates and large carnivores. Ultimately, the question is: Can we pursue treatments that aim to allow the body to effectively adapt to cancer, as opposed to waging an all-out war on cancerous tumors?

Recently, Aktipis and Maley have received a grant from the Arizona Biomedical Research Centre, part of the Arizona Department of Health Services, to launch a breast cancer clinical trial with the Mayo Clinic using adaptive therapy. Their work was featured in the April edition of Wired magazine, in an article titled “A clever new strategy for treating cancer, thanks to Darwin.”

Cancer garden project team member Byron Sampson, landscape architect and associate director of ASU’s Office of the University Architect, lost both his mother and father to cancer. Sampson, himself, is a brain tumor survivor.

“What really resonates with me is living with it, instead of battling with it like a war,” Sampson said. “If you look at it differently, it’s just abnormal cell growth. It’s not a bad thing, it’s just different.”

Perhaps the cacti know more than we yet understand. Crested cacti survive in the harsh conditions of the desert, even with mutations and unusual growth patterns. These beautiful plants may have a great deal to teach us about how we can survive and thrive in the face of cancer.

“The future is living with cancer rather than dying of it,” said Aktipis, as she closed her talk and led guests to admire the cacti.

Written by Dianne Price

More Science and technology

Hack like you 'meme' it

What do pepperoni pizza, cat memes and an online dojo have in common?It turns out, these are all essential elements of a great…

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive —…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper…