An English master’s student, a business sophomore and an urban planning undergrad walk into a classroom. There is no punchline here, and they are all in the right place.

The apparent motley crew is gathered on a recent morning in February to take on a formidable task: The title of the course is nothing less than “Rebuilding Puerto Rico.” It’s one of three lab courses being offered during the spring 2019 semester through the ASU Humanities Lab, an initiative launched by University and Regents’ Professor Sally Kitch in 2017.

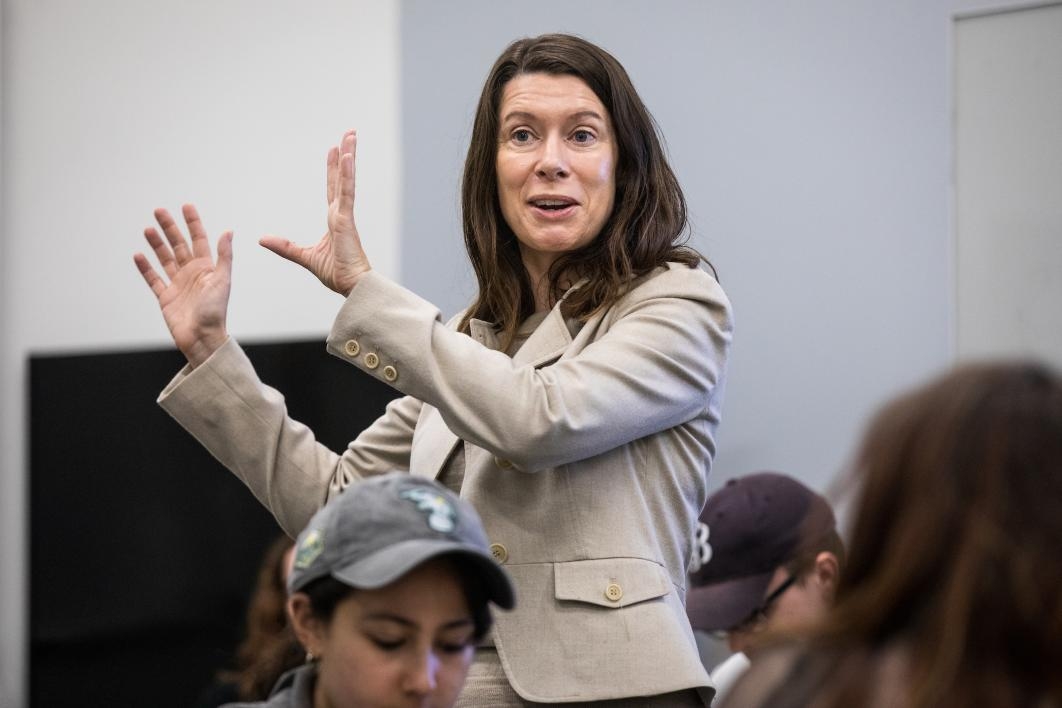

Kitch (pictured above) previously served as founding director of the faculty-oriented Institute for Humanities Research (IHR).

“I started the Humanities Lab because I realized that our students were not benefitting from the kind of interdisciplinary, exploratory experiences faculty were getting through the IHR,” she said. “So I wanted to see if we could establish a way for students to get that experience; to recognize the humanities as important for approaching and addressing today’s challenges, because the kinds of questions that really plague us are humanistic at their core.

“They’re about values and culture and understanding the way people form beliefs and the kinds of attitudes we carry around with us and the way we all live in our own narratives. And encountering that is essential for solving these problems.”

The other two labs offered this semester are “The Future of Cars” and “Facing Immigration.”

The labs are open to students of all disciplines and experience levels — from first-years to master’s — and each one is co-taught by a pair of professors, usually from fields traditionally considered incompatible (“Rebuilding Puerto Rico” is taught by a philosopher and a sustainability scientist).

Community engagement is another important aspect of the labs; from the very beginning of the course, students are given the directive that their final project is to be something that is shared with the community in a meaningful way.

All of this ensures both interdisciplinary and intergenerational collaboration.

“The lab is designed to help students look at problems from multiple perspectives and understand not only what kinds of knowledge they need in order to address these problems but that at different stages of your life, you're going to think differently about these things,” Kitch said.

Last semester, students in the initial “Facing Immigration” lab teamed up with students of ASU’s Osher Lifelong Learning Institute, which provides university-quality learning experiences for adults age 50 and older, on a mural that reflected their multi-generational immigration stories.

The Humanities Lab occupies its own unique physical space in the newly renovated Ross-Blakley Hall on ASU’s Tempe campus. It features two media stations, whiteboards for brainstorming and rough tables where students can work together on hands-on projects.

“I'm envisioning that maybe one day we'll have these lab spaces all over and we’ll be able to offer these labs in every building on campus,” Kitch said. “The contemporary workplace and certainly the future is extremely collaborative, and we hope that the team-building skills they get from this will be translatable for them on their resumes so they can say, ‘I've thought hard about these challenges and I'm ready to problem-solve.”

Topics of the labs are decided based on assessments of current events and relevant issues, as well as faculty interest and expertise in those areas.

Rebuilding Puerto Rico

“Rebuilding Puerto Rico” instructor José Lobo, an associate research professor in the School of Sustainability, originally hails from the island. Elizabeth Brake, an associate professor of philosophy in the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, developed an interest in disaster recovery while on research leave at Tulane University in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina left the city decimated.

“I’m a political philosopher and ethicist, so I think about things like justice and moral principles in a more theoretical way,” Brake said. “So this is an amazing opportunity to be in dialogue with someone who has very specific scientific and technical knowledge about an issue.”

Brake and Lobo’s students are still in the beginning stages of planning their final projects, but they’ve already made impressive progress. As is the case in every Humanities Lab course, they are split into smaller groups, sometimes called committees, each with a different priority.

RELATED: Project to develop understanding between sustainability scientists and philosophers

Morgan Heeder, an English master’s student with a focus on post-colonial environmentalism, is walking her group through a digital video she created to demonstrate the extent of physical destruction caused by Hurricane Maria. It begins in outer space, planet Earth a small, blue dot, and then zooms in on the island’s capital of San Juan to show areas of massive flooding, severe coral reef damage and communities isolated by mudslides.

Heeder used data collected from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to inform the graphic depictions. The plan is to share the video with the public at ASU Open Door.

“I think a lot of people just don’t understand how much of this was going on and exactly what the damages were and the effects of them,” Heeder said.

Future of Cars

“I hate driving,” said Patrick Roberts, an urban planning senior in the “Future of Cars” lab course. Roberts commutes to Tempe from Apache Junction every day, and he’s sick of it. So he enrolled in the lab as a way to consider a better transportation alternative.

Today, he and the other students in the lab are considering such questions as whether people would be more interested in speed or environmentally friendly transport, how a city might be designed around that and who would have access to it.

Lab instructors David King, an assistant professor in the School of Geological Sciences and Urban Planning, and Thaddeus Miller, an assistant professor in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society, both come from a science and technology policy background but are excited at the prospect of considering the future of transport from a cultural approach.

Generating a future that is more desirable, Miller said, “is really a humanities question about what values you have.”

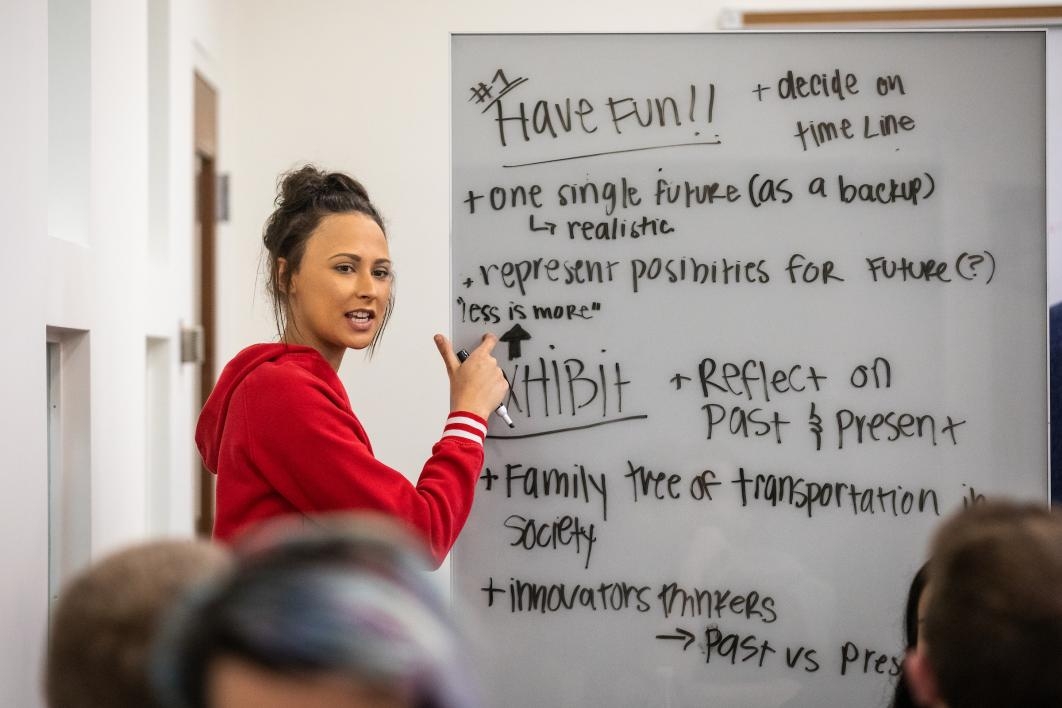

At the next class meeting, King and Miller will take their students on a field trip to Local Motors in Chandler, a company that manufactures vehicles using 3D printing and designs suggested by people online. They hope it’ll get them thinking about ways to incorporate what they learn into their final project, which will include a documentary on the history and future of the automobile, an exhibit showcasing how transportation has evolved over time and a 3D rendering of the car of the future — all of which will be on display to the community at Emerge, ASU’s “Festival of Futures,” on March 30.

Facing Immigration

The vast majority of people who call themselves Americans today have an immigration story from some point in their ancestral history, whether it’s several generations removed or their own personal account. That’s what School of Human Evolution and Social Change Assistant Professor Emir Estrada and Associate Professor of Latin American history Alexander Aviña want students in their “Facing Immigration” lab course to understand.

The professors shared their own immigration stories (both are first-generation Americans with Mexican roots) with the class and are now encouraging them to share theirs with each other and the community through art. And though they share a similar story, “immigration doesn’t equal Latino,” Estrada said.

Undecided sophomore Alexis Robinson proves her point. She grew up in Maine but, through this lab, learned that her ancestors originally came to America from France, via Canada, and were among the “filles du roi,” or “The King's Daughters,” a term used to refer to the approximately 800 young French women who immigrated there between 1663 and 1673 as part of a program sponsored by King Louis XIV of France to boost population.

“Immigration is a hot topic,” Robinson said. “It’s cool to learn about it from another perspective.”

Students in the lab organized a public art exhibit Feb. 20 featuring pieces they created that tell their immigration stories. Los Angeles artist Ramiro Gomez, known for his public art that brings visibility to immigrant workers, served as a special guest speaker.

“I see this as an opportunity to teach my students about immigration issues through art but also to empower them to reach out to communities and use art as a tool to disseminate information that they’re learning in the class,” Estrada said.

More to explore

In future semesters, the Humanities Lab will collaborate with faculty from the School of Earth and Space Exploration on the topic of “Life Without Earth,” and the College of Health Solutions on the topics “Health and Disability” and “Health Across the Lifespan.”

“Our college recently re-envisioned itself,” said Tannah Broman, a principle lecturer at the College of Health Solutions who is working with Kitch on creating the curriculum for the health-themed labs. “Part of that is knowing that we can’t really care for people without an understanding of humanities issues and the role they play in health care. It’s not only about knowing the science and policies. Those things don’t really make sense unless we can contextualize them within issues of race, gender, culture, etc.”

Other issues the Humanities Lab will explore include information overload and race, genes and culture. Kitch is working on developing a certificate for the lab, which will be offered through the School of Social Transformation.

Early in the process of creating the lab, Kitch met with faculty from across the country at a conference in Washington, D.C., hosted by the National Endowment for the Humanities to see what kinds of similar projects they had in the works. The only other institution that had a comparable, student-centric pedagogical unit was Duke University in North Carolina.

“I think this is right on target for ASU's charter and mission,” Kitch said. “We have these design principles to leverage our place, to have use-inspired research, to prepare our students to meet the grand social challenges of our day. … This is my way of saying, ‘Let's bring ASU's mission to the students as directly as possible.’

“And the thing that I’ve learned is that given enough rope and motivation, these students are capable of amazing things.”

Top photo: University and Regents' Professor Sally Kitch, founding director of the Institute for Humanities Research, talks on Feb. 6 with sustainability freshman Riley Pass (left) and architecture freshman Kenneth Velasquez during "Facing Immigration," a Humanities Lab co-taught by Assistant Professor Emir Estrada and Associate Professor Alexander Aviña. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

More Law, journalism and politics

Can elections results be counted quickly yet reliably?

Election results that are released as quickly as the public demands but are reliable enough to earn wide acceptance may not always be possible.At least that's what a bipartisan panel of elections…

Spring break trip to Hawaiʻi provides insight into Indigenous law

A group of Arizona State University law students spent a week in Hawaiʻi for spring break. And while they did take in some of the sites, sounds and tastes of the tropical destination, the trip…

LA journalists and officials gather to connect and salute fire coverage

Recognition of Los Angeles-area media coverage of the region’s January wildfires was the primary message as hundreds gathered at ASU California Center Broadway for an annual convening of journalists…