The public lecture Oxford Professor Jonathan Bate delivered Tuesday night at Changing Hands Bookstore in Phoenix, cheekily titled "The End of the World As We Know It," contained just as many pop culture nods — R.E.M.’s similarly titled late-1980s alternative hit made an appearance — as it did renowned literary and ancient mythological references (the Epic of Gilgamesh and Deucalion, son of Prometheus, turned out for the event as well).

The sheer range of apocalyptic narratives Bate was able to reference would seem to make a good case for his assertion that, at least in Western storytelling traditions, humans are obsessed with endings.

Bate’s talk was the second of three in his “How the Humanities Can Save the Planet” lecture series, taking place during his spring 2019 residency at Arizona State University’s Julie Ann Wrigley Global Institute of Sustainability and presented with support from the Department of English and the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

A prominent biographer, broadcaster and eco-critic who was knighted in 2015 for his services to literary scholarship and higher education, Bate is also co-teaching an eco-literature course during his residency with ASU English Professor Mark Lussier, who introduced him at Tuesday’s event.

“He has performed a massive service for all of us in the humanities,” Lussier said.

Bate welcomed the crowd of about 50 attendees by thanking them for coming out to listen to some thoughts about the future state of the planet rather than staying in to listen to an address about the current state of the union.

He began with a brief overview of the topics addressed in each of the three lectures: The first, "Paradise Lost," looked back at the shared cross-cultural sense that there once was a better time, a Garden of Eden scenario, when humans were at one with nature; Tuesday’s lecture looked forward, at the shared cross-cultural preoccupation with doomsday narratives; and the third, "Living Sustainably," which takes place Wednesday, Feb. 20, will discuss some of the ways humanities might help to change the future.

“Past, present, future — a narrative structure,” Bate said. “One of my key arguments … about sustainability is that it needs the humanities because humanities give us narratives.”

Over the course of the next hour, Bate presented several throughout time and across cultures, all of them apocalyptic in nature, and laid out some thoughtful takeaways for each.

Works like Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” and Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 “Apocalypse Now” film adaptation of the novel hold that all empires come to an end.

“Both suggest that the road to geopolitics is always a dark one, a power play that involves imperial overreach and brings human suffering and either direct or collateral damage to ecosystems,” Bate said.

On the topic of damage to ecosystems, Bate pointed to popular science author Jared Diamond, who makes the argument in his book “Collapse” that societies succeed or fail according to how they deal with the threat of environmental change.

And stories of catastrophes, as are often told through the patented Hollywood disaster flick, often invoke a fear of invasion underpinned by race, something Bate found especially troubling for modern times.

“Our cultural studies in the last 20 years or so have focused so much on race and gender,” he said, “that we run the risk of leaving out the relationship between humans and the wider environment. (We run the risk of) losing that sense of wider ecology of which we are all a part of. Which is untimely, given our current environmental crises.”

Finally, Bate addressed the danger of utopian narratives, those that end not with disaster but the renewal that follows. One such enduring example is the biblical story of Noah and the flood.

“I would suggest that there are huge dangers in these utopian ideas, and equally huge dangers in myths of salvation in next world,” Bate said, because they can lead to carelessness for our current physical habitat.

In a handy chart, Bate displayed his list of “Pros and Cons of Apocalyptic Narratives” for the audience.

In the “pro” column:

- They serve as a reminder of the law of entropy, that all things coming to decay and disorder.

- They serve as a method of dealing with our own insignificance.

- They serve as admonitions against hubris.

- They serve as a moral imperative.

In the “con” column:

- They can provide the illusion of an earthly paradise regained.

- They can provide the illusion of a heavenly paradise achieved.

- They can provide the illusion that because there have been so many narratives throughout time and the world hasn’t ended yet, it never will.

“It’s not all doom and gloom,” Bate reassured the audience at the end of his talk, and encouraged them to make time for his final lecture, which “will talk about ways humanities can offer us a glimpse or moments of redemption,” as well as some Eastern narratives that emphasize a cyclical nature to the order of the world.

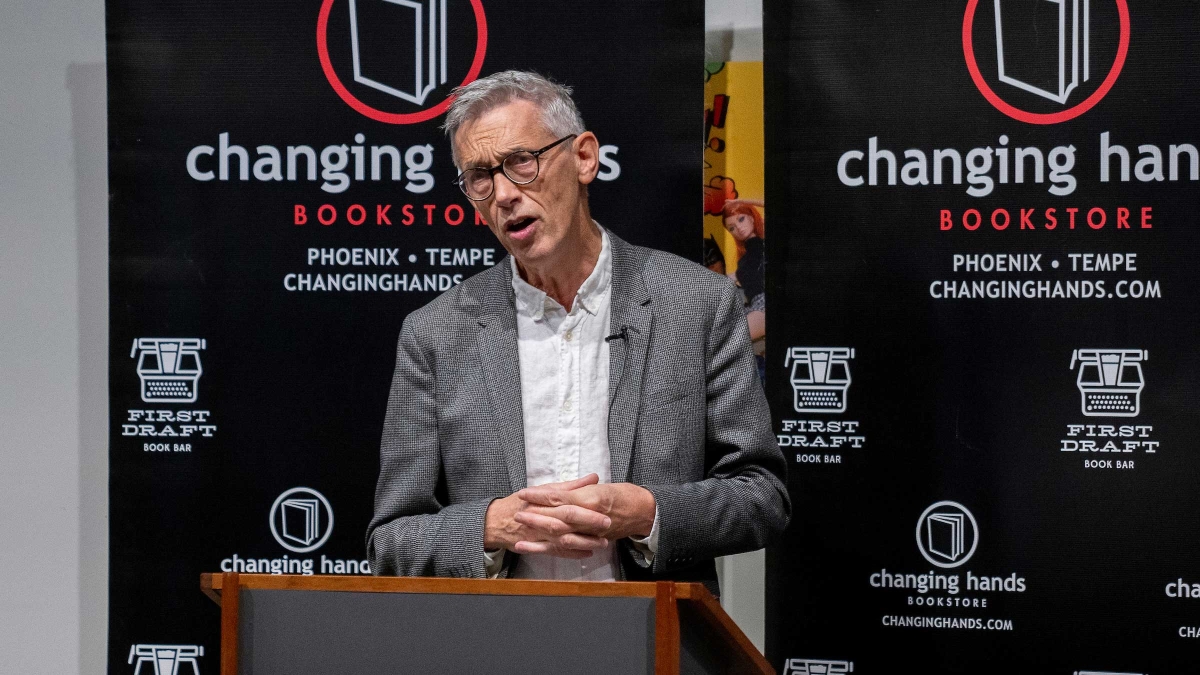

Top photo: Sir Jonathan Bate, professor of English literature at Oxford, leads a lecture on "The End of the World as We Know It" at Changing Hands Bookstore in Phoenix on Tuesday evening. Photo by Marcus Chormicle/ASU Now

More Environment and sustainability

Researcher works on changing people's mindsets to fight climate change

Meaningful action to heal the climate requires a complete shift in the way people think and perceive each other, according to an expert on social transformation who spoke at Arizona State University…

NOAA, ASU offer workshop to bridge ocean exploration, education

Oceans are vital to sustaining life on Earth, as they produce over half of the oxygen we breathe and play a crucial role in regulating the planet's climate. They also support a diverse array of…

A united front for sustainability and the economy

When four leaders of esteemed learning institutions and the mayor of Phoenix gather in one location at the same time, it’s a tip-off that something big is going down.When they’re joined by visionary…