For Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th and current Dalai Lama, his love of science began in childhood. Curious to know what made a mechanical watch tick, he took it apart and put it back together again. Despite the success of that early endeavor, he didn’t receive any formal scientific education until he was much older, something he considered a disservice when he found that it actually complemented and enhanced his Buddhist training and understanding of the scriptures.

Today, science education is part of the curriculum in Buddhist monasteries, thanks to the Dalai Lama’s resolve to make it so. And while it might seem odd from a Western perspective for a religious figure to embrace the pursuit of empirical study, the Dalai Lama espouses the belief that “all avenues of inquiry — scientific as well as spiritual — must be pursued in order to arrive at a complete picture of the truth.”

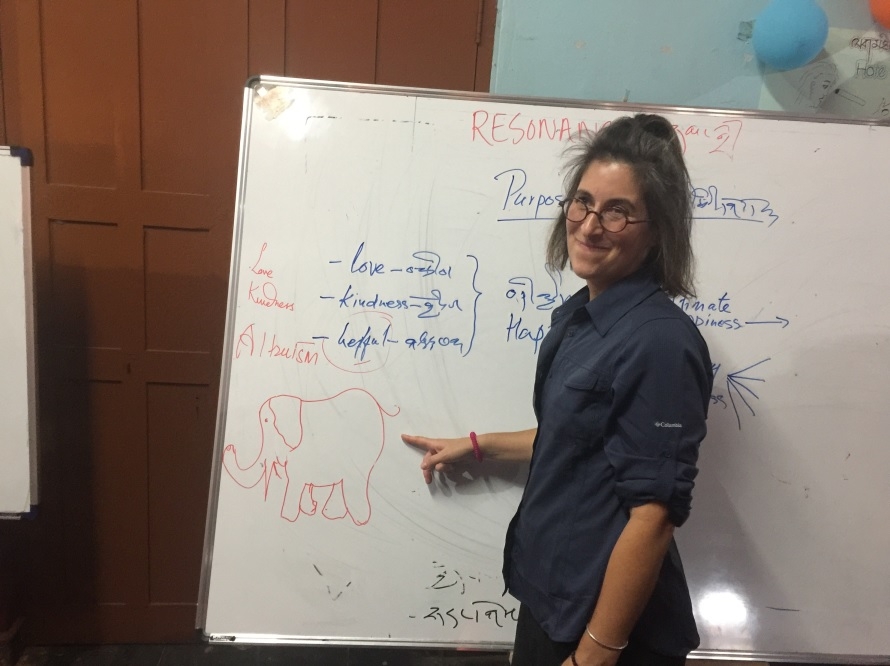

Arizona State University Associate Professor of English Jessica Early appreciates what can be gained from the intersection of seemingly disparate practices. As director of the Central Arizona Writing Project, a local offshoot of the National Writing Project, she has taught several workshops on how to write about science.

This past December, Early took that expertise to Dzongkar Choede Monastery in southern India, where she and a diverse group of colleagues participated as instructors in the Sager Science Leadership Institute, which trains monks in how to be leaders of science education and nurturers of their monastic communities’ growing relationship with science.

“I thought this was going to be something totally out of my comfort zone,” Early said. “But one of the things I’ve learned about teaching writing is how it really translates to different disciplines. So I was delighted that it was able to transfer to such a new setting and audience.”

The Sager Science Leadership Institute was created about 20 years ago with funding from Jewish-American philanthropist Bobby Sager, who sympathized with the Tibetan exile story’s similarity to the Jewish exile from Israel. Sager created the institute after learning of the Dalai Lama’s wish to educate the exiled monks in science.

Since then, the institute has established science centers at nearly every monastery in India and hosted three cohorts of roughly 30 to 40 monastics from all across the country.

Early on, the San Francisco-based educational museum Exploratorium and the National Writing Project became involved to help design the institute and supply instructors.

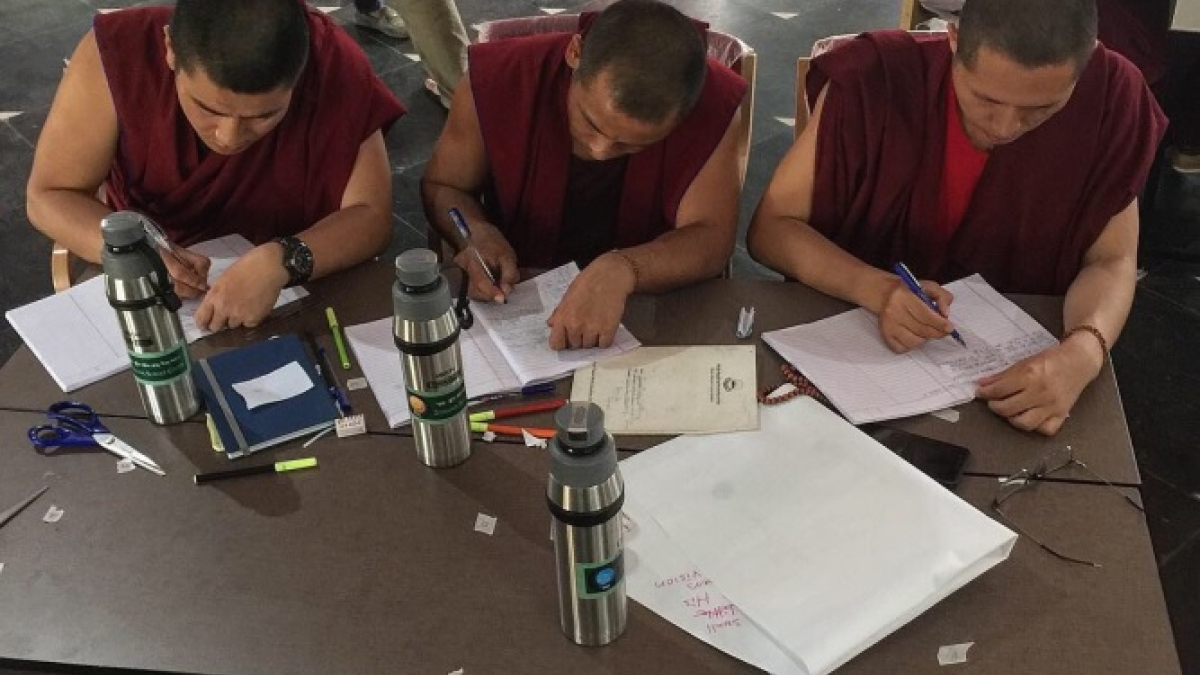

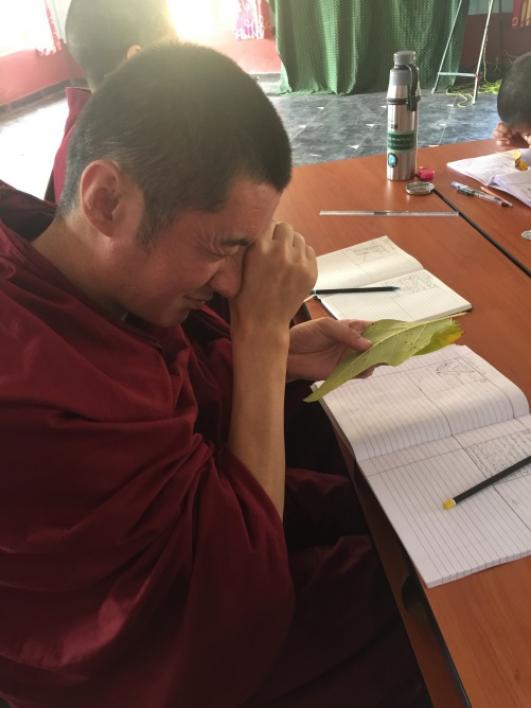

For 10 days, Early and Tom Meyer, director of the National Writing Project’s New York-based offshoot, the Hudson Valley Writing Project, worked with a translator to co-teach 22 monks how to write about science, how to write about leadership and how to write for enjoyment. Much like the workshops Early runs every summer for teachers in Arizona, the goal was to teach the monks not only how to write in a certain way, but also how to teach others how to write.

In one writing exercise, Early asked the monks to write about a favorite dish of theirs, both its personal significance as well as the recipe.

“That’s science writing,” Early said. “Having to write the ingredients and the step-by-step instructions. But then, they also wrote about why it’s special to them. So I tried to blend different genres of audience and purpose.”

Another writing exercise was influenced by Early’s book “Stirring Up Justice,” which teaches activism and changemaking.

“One of the things we talked about is how changemakers create plans for change,” she said. “So they wrote action plans that talked about their purpose, their plan, the resources they needed, the questions they had … and one of the reasons for writing the action plans was so they could use it as a proposal.”

Some of the monks proposed hosting a conference while others proposed introducing informal science education at their monasteries. Much of what the monks wrote during the institute will be put together in an anthology that they will share at their respective monasteries across the country.

The monks also got practice teaching. Every day, they taught a different Buddhist concept or fact to Early and Meyer, such as meditation and why they wear robes and why they are a certain color (they’re seen as uniforms and they choose ugly colors so as not to draw attention to themselves).

Early and Meyer were also joined by colleagues from Exploratorium and NYU’s physics department, who taught lessons on various scientific phenomena, such as electricity, the phases of the moon and the inner workings of the human brain.

All of the instructors collaborated to teach the monks how to host a science fair for elementary children, with Early and Meyer overseeing the written-explanation portion of the monks’ posters.

Early has received a research grant to publish what she learned from the experience. During her time in India, she took field notes and collected data on best practices for teaching through a translator, co-teaching and teaching students who write in dual languages, among other things.

“My work as a writing researcher is looking at the way community is created around writing and how literacy happens in a learning environment in particular contexts,” she said.

And while this was a unique context for Early, one thing she noticed was how smoothly her lessons translated between cultures.

“Teaching is very connected to your context and to the people that you’re teaching,” she said, “but it can also transfer to new contexts and new places. And that fits so well with ASU’s commitment to social embeddedness.”

Top photo: Monks participating in the Sager Science Leadership Institute write about science phenomena they have observed. Photo courtesy of Jessica Early

More Science and technology

ASU-led space telescope is ready to fly

The Star Planet Activity Research CubeSat, or SPARCS, a small space telescope that will monitor the flares and sunspot activity of low-mass stars, has now passed its pre-shipment review by NASA.…

ASU at the heart of the state's revitalized microelectronics industry

A stronger local economy, more reliable technology, and a future where our computers and devices do the impossible: that’s the transformation ASU is driving through its microelectronics research…

Breakthrough copper alloy achieves unprecedented high-temperature performance

A team of researchers from Arizona State University, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Lehigh University and Louisiana State University has developed a groundbreaking high-temperature copper alloy…