Designed to move: ASU Biomimicry Center planting inspiration with seed exhibit

Vaulting beyond velcro, the Biomimicry Center at Arizona State University is seeding new ideas for nature-inspired innovation.

Still most widely associated with the invention of velcroEngineer George de Mestral’s invented the hook-and-loop fastener inspired by the burdock plant burrs that stuck on his pants and his dog’s fur while hiking in the Swiss Alps in the 1940s., ASU researchers are walking the talk of biomimicry with a newly renovated office space and a new seed exhibit they hope will capture the imagination of innovators seeking solutions for complex human problems.

“Seeds continue to offer a bottomless design and engineering trove for many other innovations,” said Heidi Fischer, assistant director at the Biomimicry Center. “We hope that our exhibition can provide new models for some of these innovations. With new advances in imaging technologies, the average person now can have access to nature’s heretofore hidden designs and begin to imagine new design possibilities.”

Titled “Designed to Move: Seeds that Float, Fly or Hitchhike through the Desert Southwest,” the exhibit, opening Oct. 30 in the Design School South Gallery on ASU's Tempe campus is offering viewers an extraordinary look at the beauty of desert seeds as captured through the macro photography lens of Taylor James, an alumni of ASU’s Masters of Fine Arts program.

“Most people, including many botanical experts, have never seen up-close photos of desert seeds before,” Fischer said. “New visualization technologies are giving us access to the intricate designs that are largely invisible to us as we casually stroll through the desert. In the process, they uncover a trove of untapped design potential for solving many human challenges.”

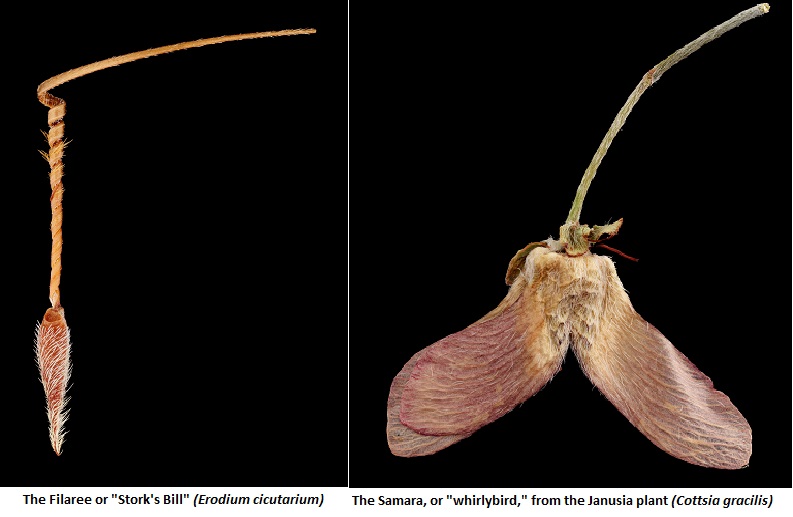

Samaras for example, a winged seedpod produced by a wide range of plants including sugar maples and the slender janusia that grows in the desert, is one such seed that is inspiring innovation. Nicknamed “whirlybird” or “helicopter seed” for its propensity to rotate airborne after detaching from the plant stem, scientists studying the aerodynamic properties of samaras are trying to mimic the seedpod's design and apply its principles to airplane wings and space probes for planetary exploration.

Biomimicry research is also delving into the clinging, coiling and self-planting behavior of the seeds produced by the filaree or “stork’s bill” plant. Among other applications, engineers are mimicking the humidity-triggered coiling and uncoiling of filaree awns to create hygrobots: tiny robots whose flexing movements are powered by daily changes in environmental humidity instead of batteries.

Fischer said the idea for the seed exhibit came about after a conversation with colleagues from ASU’s Vascular Plant Herbarium in the School of Life Sciences, the School of Art in the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts and the Desert Botanical Garden in Phoenix during a photography expedition in the desert. The collaboration led to a selection of Arizona seed species that were determined to be visually compelling and had interesting stories about seed dispersal adaptation or application through design or engineering.

Fischer said there is talk about possibly taking the seed exhibit on the road after its run at the Design School South Gallery comes to a close. The hope, she said, is to get national parks, natural history museums and herbaria interested in hosting all or part of the show’s modular design. She also hopes the exhibit will prompt people to think about seeds in a completely different way when they come across them in the desert.

Office space: The biomimicry way

While biomimicry remains a somewhat vague concept to the general public 20 years after the publication of Janine Benyus’ seminal bookJanine Benyus has authored several books on biomimicry including the widely-referenced "Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature." on the subject, the engineering of modern innovations such as high-speed bullet trains (inspired by the beak Kingfisher bird), and sharkskin swimsuits (modeled after the dermal denticles on a shark’s skin) illustrate how many biomimicry applications may just be hidden in plain sight.

“For too long our built environment has been seen as separate from nature,” said Sara el Sayed, a research associate at the Biomimicry Center at ASU. “Bringing biomimicry to the built environment allows us to create cities, buildings, products and human systems that function like the natural world — sustainable and aesthetically beautiful.”

Still, as Dayna Baumeister, director of the Biomimicry Center and co-founder of Biomimicry 3.8, is quick to point out, just mimicking the shape of something in nature or emulating one aspect of an organism does not necessarily make a design biomimetic.

Biomimicry, Baumeister said, emulates the design principles of nature to achieve functional similarity.

“A chair may look like a leaf but it won’t function as one. Now imagine if that same chair was able to harness photons from sunlight to create energy functioning like the leaf — that’s a step closer. Emulating the deep patterns in nature, which we call Life’s Principles, can result in even more innovative and sustainable solutions. These overarching characteristics and deep patterns are guidelines we use in designing.”

Life’s Principles were consciously applied to the redesign of the office space Baumeister and her team inhabit in the College of Design South building on ASU’s Tempe campus. And, with some help from local design firm Architekton and fabrication firm Nicomia, the team at The Biomimicry Center is now enjoying a more sustainable and resource efficient environment inspired by nature.

“We created modular furniture that ‘adapts to changing conditions,’” Baumeister said, pointing out that the furniture in the Biomimicry Center’s office space can be reconfigured based on changing needs such as social gatherings, classes, office functions or meetings. “We have ‘locally attuned’ lights that mimic the circadian rhythm of day and night cycles, ensuring that we have a healthy work environment. And our recycled ceiling mimics the sound buffering and light-distributing design principles of a forest canopy.”

According to Baumeister, the finish plywood for the office’s furniture and shelving is Purebond, which uses soy proteins inspired by the blue mussel to create natural glues with no off-gassing and the paint is VOCVolatile Organic Compounds, or VOC, refers to certain carbon compounds, that participate in atmospheric photochemical reactions.-free, thanks to application of what she calls “life-friendly chemistry.” This, Baumeister promises, is “just the beginning.”

The Biomimicry Center is offering the public a look at its newly remodeled office at the opening of the macro photography seed exhibit “Designed to Move: Seeds that Float, Fly or Hitchhike through the Desert Southwest” from 5 to 8 p.m. on Tuesday, Oct. 30. The evening will include a Gallery Talk at 6 p.m. and an original soundscape composition by Garth Paine, an acoustic ecologist in ASU’s School of Arts Media and Engineering.

Top photo courtesy of Taylor James

More Science and technology

ASU student researchers get early, hands-on experience in engineering research

Using computer science to aid endangered species reintroduction, enhance software engineering education and improve semiconductor material performance are just some of the ways Arizona State…

ASU professor honored with prestigious award for being a cybersecurity trailblazer

At first, he thought it was a drill.On Sept. 11, 2001, Gail-Joon Ahn sat in a conference room in Fort Meade, Maryland. The cybersecurity researcher was part of a group that had been invited…

Training stellar students to secure semiconductors

In the wetlands of King’s Bay, Georgia, the sail of a nuclear-powered Trident II Submarine laden with sophisticated computer equipment juts out of the marshy waters. In a medical center, a cardiac…