New observations by two Arizona State University astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope have caught a red dwarf star in a violent outburst, or superflare. The blast of radiation was more powerful than any such outburst ever detected from the sun and would likely affect the habitability of any planets orbiting it.

Moreover, the astronomers said, such superflares appear more common in younger red dwarfs, which erupt 100 to 1,000 times more powerfully than they will when they age.

The superflare was detected as part of a Hubble Space Telescope observing program dubbed HAZMAT, which stands for "HAbitable Zones and M dwarf Activity across Time." The program surveys red dwarfs (also known as M dwarfs) at three different ages — young, intermediate and old — and observes them in ultraviolet light, where they show the most activity.

"Red dwarf stars are the smallest, most common and longest-lived stars in the galaxy," said Evgenya Shkolnik, an assistant professor in ASU's School of Earth and Space Exploration and the HAZMAT program's principal investigator. "In addition, we think that most red dwarf stars have systems of planets orbiting them."

The Hubble telescope's orbit above Earth's atmosphere gives it clear, unhindered views at ultraviolet wavelengths. The flares are believed to be powered by intense magnetic fields that get tangled by the roiling motions of the stellar atmosphere. When the tangling gets too intense, the fields break and reconnect, unleashing tremendous amounts of energy.

ASU postdoctoral researcher Parke Loyd is the first author on the paper (to be published in the Astrophysical Journal) that reports on the stellar outbursts.

"When I realized the sheer amount of light the superflare emitted, I sat looking at my computer screen for quite some time just thinking, 'Whoa,'" said Loyd. “Gathering data on young red dwarfs has been especially important because we suspected these stars would be quite unruly in their youth, which is the first hundred million years or so after they form.”

He added: "Most of the potentially habitable planets in our galaxy have had to withstand intense flares like the ones we observed at some point in their life. That's a sobering thought."

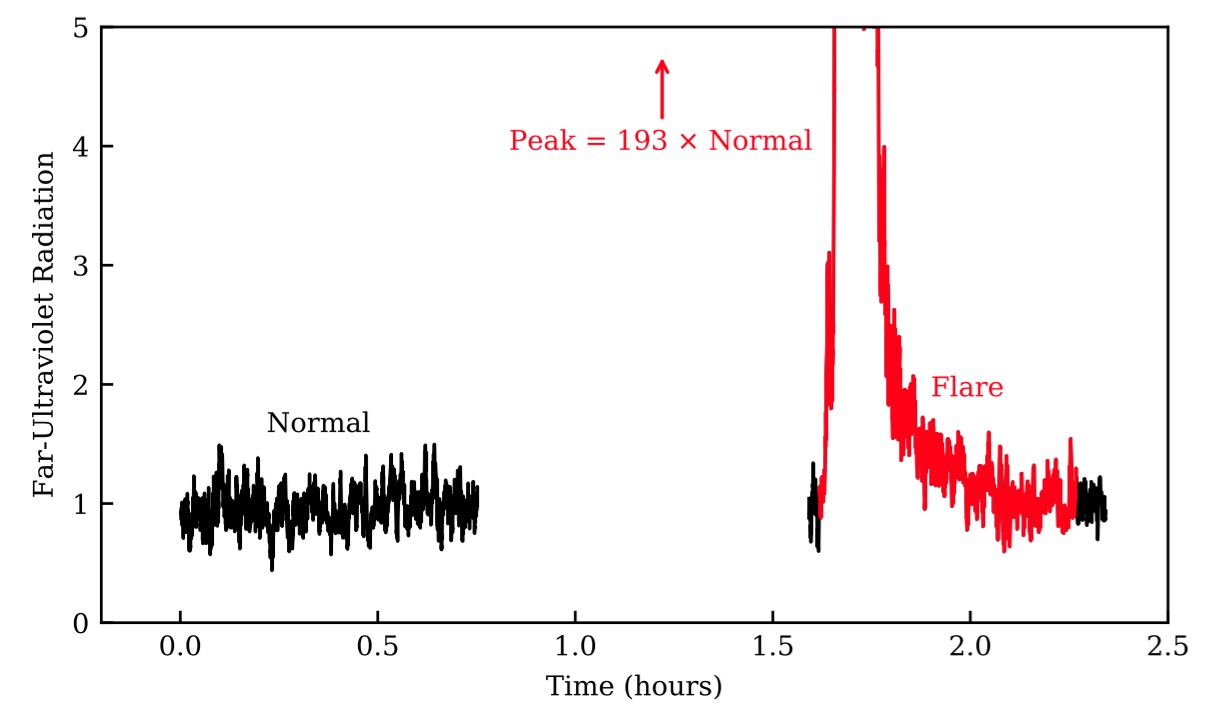

Observations with the Hubble Space Telescope discovered a superflare (red line) that caused a red dwarf star's brightness in the far ultraviolet to abruptly increase by a factor of nearly 200. Credit: P. Loyd/ASU

Rough environment for planets

About three-quarters of the stars in our Milky Way galaxy are red dwarfs. Most of the galaxy’s "habitable-zone" planets — planets orbiting their stars at a distance where temperatures are moderate enough for liquid water to exist on their surface — orbit red dwarfs. In fact, the nearest star to our sun, a red dwarf named Proxima Centauri, has an Earth-size planet in its habitable zone.

However, red dwarfs — especially young red dwarfs — are active stars, producing flares that could blast out so much energy that it disrupts and possibly strips off the atmospheres of these fledgling planets.

"The goal of the HAZMAT program is to understand the habitability of planets around low-mass stars," explained Shkolnik. "These low-mass stars are critically important in understanding planetary atmospheres." Ultraviolet radiation can modify the chemistry in a planet’s atmosphere or potentially remove that atmosphere.

The observations reported in the Astrophysical Journal examined the flare frequency of 12 young (40-million-year-old) red dwarfs and represent just the first part of the HAZMAT program. These stars show that young low-mass stars flare much more frequently and more energetically than old stars and middle-age stars like our sun — as evidenced by the superflare.

"With the sun, we have a hundred years of good observations," said Loyd. "And in that time, we’ve seen one, maybe two, flares that have an energy approaching that of the superflare. In a little less than a day’s worth of Hubble observations of these young stars, we caught the superflare. This means that we're looking at superflares happening every day or even a few times a day."

Could superflares of such frequency and intensity bathe young planets in so much ultraviolet radiation that they forever rule out any chance of habitability?

According to Loyd: "Flares like we observed have the capacity to strip away the atmosphere from a planet. But that doesn't necessarily mean doom and gloom for life on the planet. It just might be different life than we imagine. Or there might be other processes that could replenish the atmosphere of the planet. It’s certainly a harsh environment, but I would hesitate to call it a sterile environment."

The next part of the HAZMAT study will be to study intermediate-age red dwarfs that are 650 million years old. Then the oldest red dwarfs will be analyzed and compared with the young and intermediate stars to understand the evolution of the high-energy-radiation environment for planets around these low-mass stars.

Red dwarfs, which are estimated to burn as long as a trillion years, have a vast stretch of time available to eventually host evolving, habitable planets.

“They just have many more opportunities for life to evolve, given their longevity,” said Shkolnik. "I don't think we know for sure one way or another about whether planets orbiting red dwarfs are habitable just yet, but I think time will tell.

"It's great that we're living in a time when we have the technology to actually answer these kinds of questions, rather than just philosophize about them."

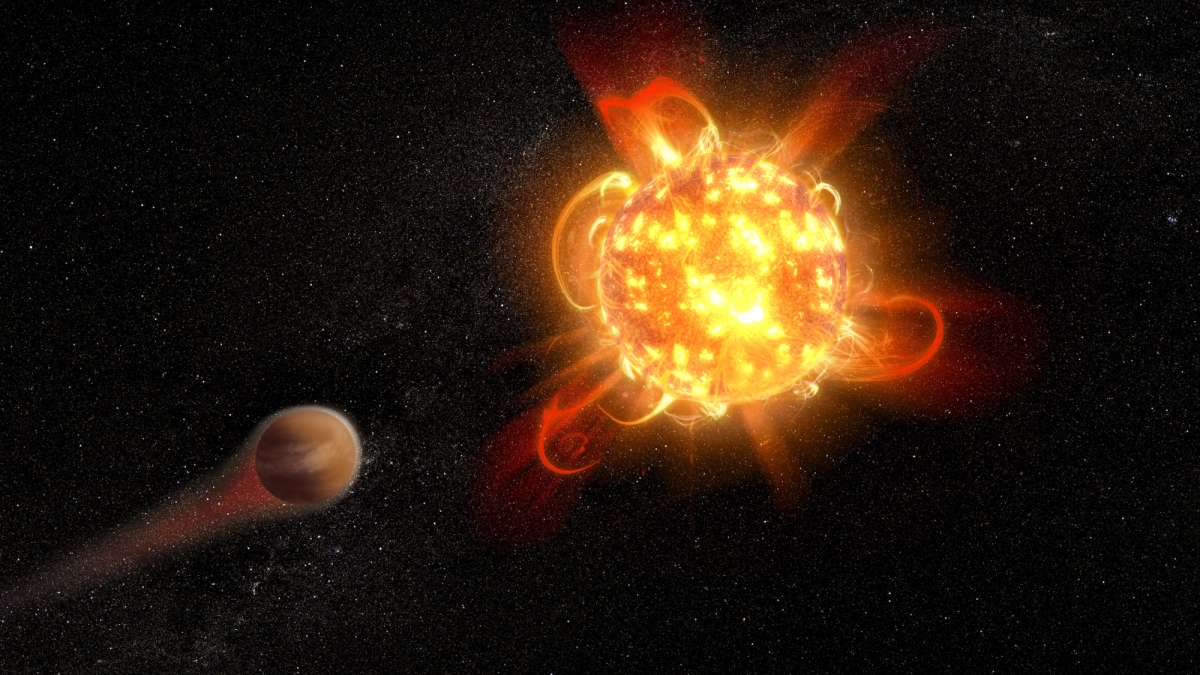

Top photo: Violent outbursts of seething gas from young red dwarfs may make conditions uninhabitable on fledgling planets. In this artist’s rendering, an active, young red dwarf (right) is stripping the atmosphere from an orbiting planet (left). ASU astronomers have found that flares from the youngest red dwarfs they surveyed — approximately 40 million years old — are 100 to 1,000 times more energetic than when the stars are older. They also detected one of the most intense stellar flares ever observed in ultraviolet light — more energetic than the most powerful flare ever recorded from our Sun. Credit: NASA, ESA, and D. Player (STScI)

More Science and technology

Breakthrough copper alloy achieves unprecedented high-temperature performance

A team of researchers from Arizona State University, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Lehigh University and Louisiana State University has developed a groundbreaking high-temperature copper alloy…

4 ASU researchers named senior members of the National Academy of Inventors

The National Academy of Inventors recently named four Arizona State University researchers as senior members to the prestigious organization.Professor Qiang Chen and associate professors Matthew…

Transforming Arizona’s highways for a smoother drive

Imagine you’re driving down a smooth stretch of road. Your tires have firm traction. There are no potholes you need to swerve to avoid. Your suspension feels responsive. You’re relaxed and focused on…