The granddaughter of a man who served as the warden of Angola, the Louisiana State Penitentiary sometimes referred to as “the Alcatraz of the South,” Leah Sarat sees the irony in helming a project that asks people to rethink America’s prison system.

But back in 2015, when a colleague introduced her to "States of Incarceration," a traveling exhibition that seeks to shed light on the topic of mass incarceration in the U.S., she was intrigued.

An associate professor in Arizona State University’s School of Historical, Religious and Philosophical Studies, Sarat’s research explores the intersection of religion and migration in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands. At the time she learned of the exhibition, she had been focusing on immigrant detention. It was the perfect opportunity to bring discussion of the issue out of the ivory tower and into the lives of people affected by it.

“This is something that allows myself and my students to really engage with our surrounding community,” Sarat said. “I have a passion for any project that can connect the academic world and all the expertise that we bring, the theoretical and historical background that we can bring, to the community, to people who are asking questions and want to know more about certain topics.”

Launched in New York City in April 2016, “States of Incarceration” is run by the Humanities Action Lab, a coalition of more than 20 universities that collaborate to produce projects that foster public dialogue on pressing social issues by exploring local histories to understand shared global concerns. More than 700 university students and formerly incarcerated individuals from 30 communities across the country contributed to the exhibition, funded by a $310,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Beginning Wednesday and running through Oct. 27, “States of Incarceration” will be on display at Burton Barr Central Library in Phoenix. The official launch will take place Friday, Sept. 7, on the main floor of the library with a free screening of the documentary “1994: Detention at Crossroads,” followed by a Q&A with the film’s director, ASU alum Judith Perera.

“We are pleased to offer our space as a place for our communities to have access to an exploration of a community issue,” said Lee Franklin, the library’s community relations manager. “Being housed in a public library, it allows for those attending, participating and exploring any topic to continue a further discovery of this and related topics through additional library materials and programs.”

Since 2016, Phoenix Public Library has such offered workshops and resources to formerly incarcerated individuals as the Set Aside Clinic and Second Chance/Re-Entry job fairs, which help remove barriers to employment, housing and voting in the hopes of reducing recidivism.

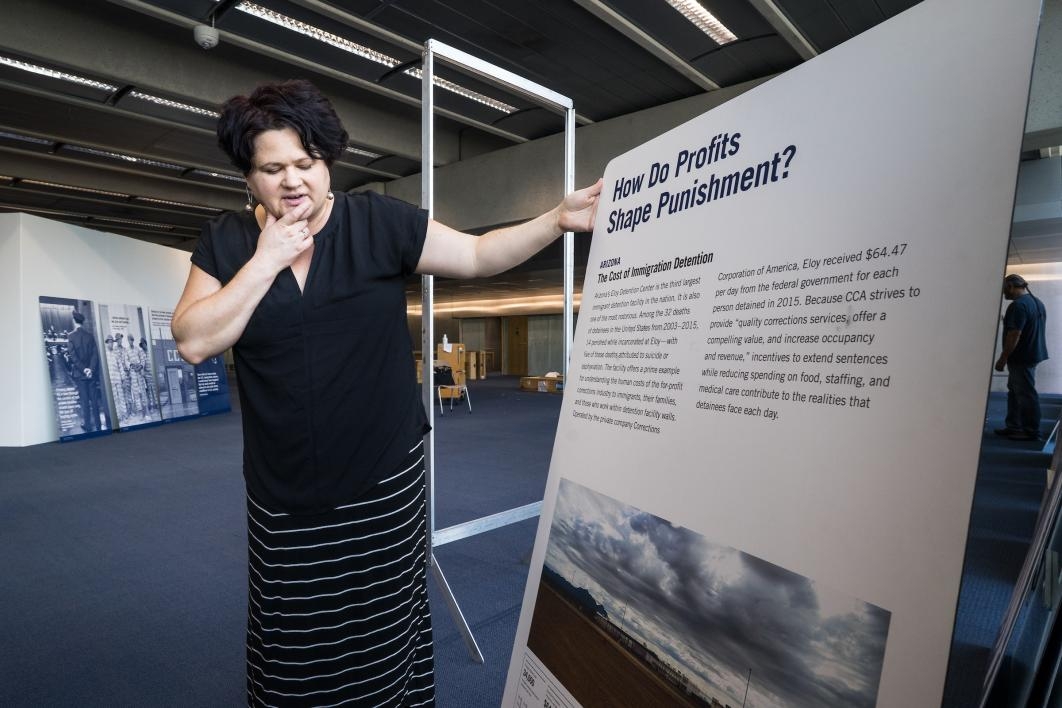

The “States of Incarceration” exhibition will include panels created by students of Sarat’s history graduate course, “Incarceration, Immigration and the Borderlands.” The panels — collectively titled “The Cost of Immigrant Detention: How Do Profits Shape Punishment?” — feature Arizona’s Eloy Detention Center, a privately run immigrant detention facility that can hold more than 1,500 men and women at any given time.

In fall 2015, Sarat and her students took the hourlong drive down to Eloy, about halfway between Phoenix and Tucson, to visit the detention center in person. It was Perera’s first foray into the subject. The images she saw during that trip have stayed with her — trash bags filled with the possessions of recently housed detainees lined the halls from one end to another — as well as other sensory recollections.

“It was just shocking to me on so many levels, but one of the things that always stood out was the unique smell, like cleaning liquid,” she said. “And it was very cold. Literally but also metaphorically, the atmosphere was very cold.”

Her reflection on that visit was recorded as part of the audio component of the exhibition, which visitors can listen to with their smartphones. (There will also be Spanish-language translations available in a pamphlet.)

Sarat and her students focused on immigrant detention for the panels they produced because of the proximity and relevance in the state. She explained, “Arizona is often ground zero for national attention on immigration, but we thought it was important to bring that into the larger story about incarceration because sometimes those conversations don’t happen together.”

The purpose of immigrant detention facilities is purely administrative holding. “In practice, though,” Sarat said, “it’s no difference from prison.”

She and her students also visited the public Florence Correctional Center, where the difference between a for-profit facility and a government facility was most noticeable to them in the quality of food (they said Florence’s offerings were bearable whereas Eloy’s consisted of a “glob of mashed-together mystery meat” billed as chicken-fried steak). But that difference also affects the quality of health care offered and even the amount of training guards receive.

Afterward, Perera was haunted by lingering questions: Why are incarceration and detention facilities run this way? When did they become this way? What factors contribute to it?

Having worked as a lawyer before going back to get her doctorate in history from the School of Historical, Religious and Philosophical Studies, she decided to take on a few pro bono cases for some of the detainees she had met. That’s when she realized she could combine her legal expertise with her history chops to find the answers to those questions and try to make change.

“As a lawyer, you can only go so far. But as a historian, you don’t have any limits. You can go back in the archive and try to understand how the system came to be,” Perera said.

She has since taken the 300-page dissertation that came out of that investigation and turned it into a documentary (the same one that will be screened at the Sept. 7 launch of the exhibition).

“People can either agree or disagree, but after viewing it, they’ll be able to carry on the conversation with a more historically grounded perspective,” she said.

In addition to the documentary screening, a whole host of events will take place throughout September and October in support of the exhibition, including an event in cooperation with the Mass Story Lab Project, which trains individuals impacted by incarceration in storytelling techniques to share their experience.

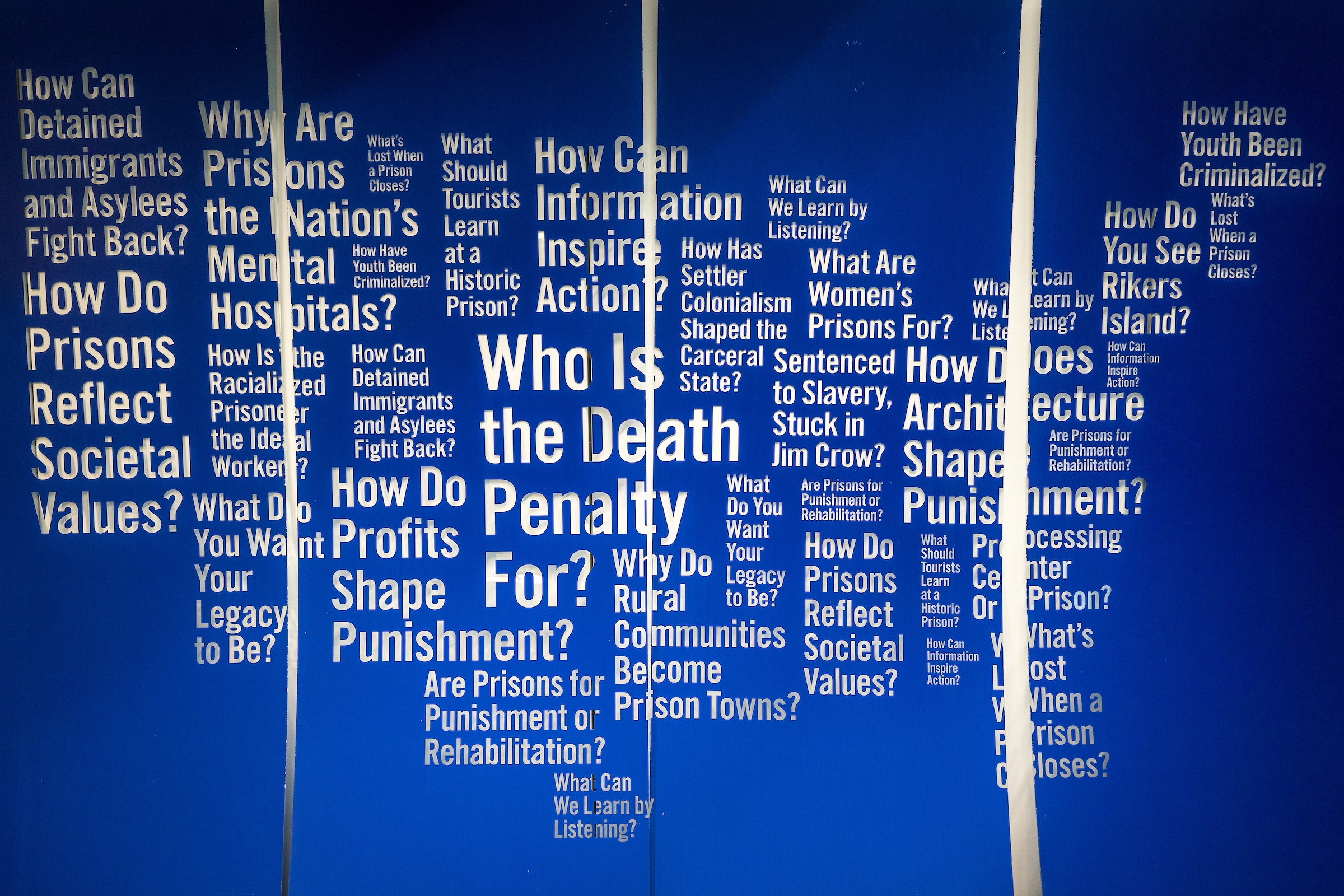

“Incarceration is often stigmatized,” Sarat said. “We might have neighbors and friends and people we interact with every day who have been impacted by it and we just don’t know. This is a way to externalize that and also tackle some serious questions. The exhibit does not seek to answer those questions, though; it just seeks to amplify a public conversation. And we’re not starting the conversation; it’s already going on. This is just a really exciting chance to connect stories from the Southwest to the larger national conversation.

“I started this project thinking that we need to lock a lot of people up for safety. But after going through the process and seeing people’s stories, I think we need to take a step back and question the default assumption that putting people in prisons is the best approach to public safety and start looking at other models.”

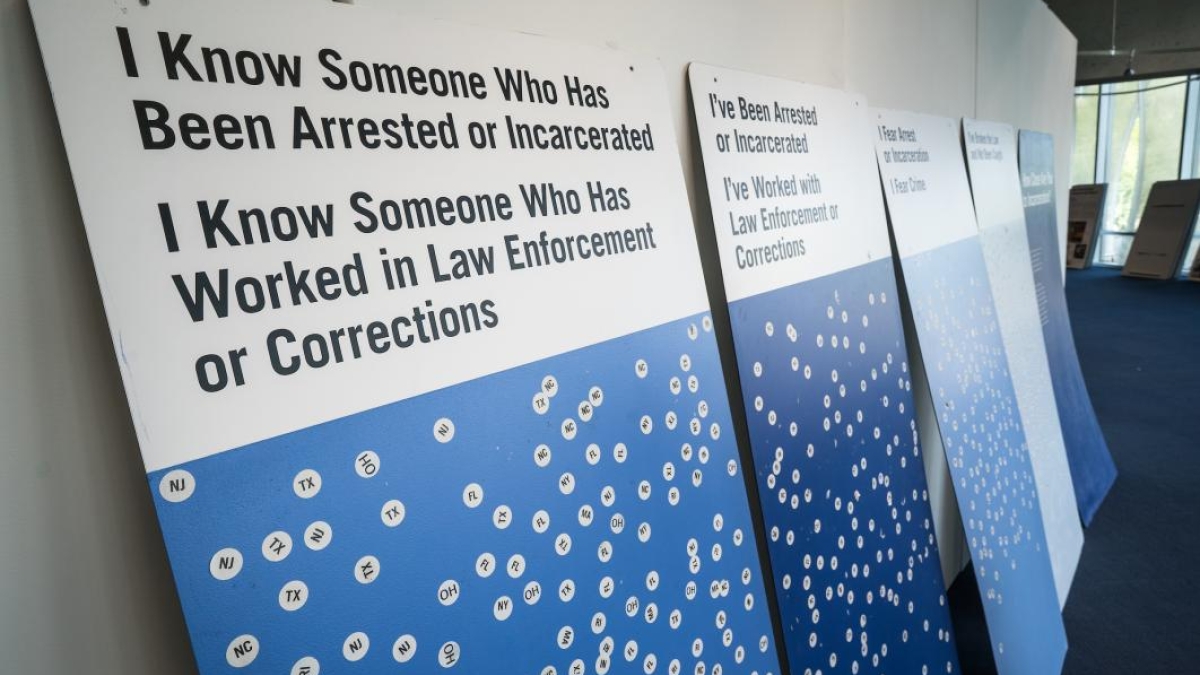

Top photo: Part of the exhibit features panels on which visitors can anonymously place stickers of their location to demonstrate the number of people affected by incarceration and to what degree. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU professor, alum named Yamaha '40 Under 40' outstanding music educators

A music career conference that connects college students with such industry leaders as Timbaland. A K–12 program that incorporates technology into music so that students are using digital tools to…

ASU's Poitier Film School to host master classes, screening series with visionary filmmakers

Rodrigo Reyes, the acclaimed Mexican American filmmaker and Guggenheim Fellow whose 2022 documentary “Sansón and Me” won the Best Film Award at Sheffield DocFest, has built his career with films that…

Pen Project helps unlock writing talent for incarcerated writers

It’s a typical Monday afternoon and Lance Graham is on his way to the Arizona State Prison in Goodyear.It’s a familiar scene. Graham has been in prison before.“I feel comfortable in prison because of…