Arizona State University embraces the heat of the Sonoran Desert it calls home. Its influence is everywhere, from the aptly named “Inferno” student section at sporting events to the university’s iconic Sun Devil mascot.

Research has even shown that athletes who train in the heat show improved performance in all temperatures. However, ensuring enough fluid intake in those conditions is key.

New research coming out of the recently established AthleatThe “e-a-t-“ in “Athleat” is a nod to the lab’s focus on nutrition. Field Lab, a joint initiative of ASU’s College of Health Solutions’ nutrition program and Sun Devil Athletics, seeks to address the unique environment ASU student-athletes contend with by focusing on hydration.

“The difficulty here is that it’s so hot and dry that people sweat much more than they normally would in a more moderate environment,” said Floris Wardenaar, an assistant professor of nutrition and founder of the Athleat Field Lab. “So there’s a higher chance of becoming dehydrated and not replenishing bodily fluids as well as we should. That fluid imbalance can affect health and will certainly affect performance.”

The lab represents a symbiotic relationship between the College of Health Solutions and Sun Devil Athletics. It allows students — graduate and undergraduate — to participate in the advancement of sports nutrition research in a field setting, under the guidance of experienced professors, while enhancing the performance of ASU teams who serve as study subjects and benefit from whatever knowledge is gleaned.

Together with Sun Devil Athletics (SDA) director of sports nutrition Amber Yudell, Wardenaar teaches NTR 494: Applied Sports Nutrition, a course in which students get the opportunity to follow a weekly lecture and discussion and volunteer as a nutrition intern with SDA. Half of the students assist Yudell in areas such as the nutrition bar in the football facility, and the other half assist Wardenaar with Athleat Field Lab studies involving SDA student-athletes.

“We are a large research university, so if we have all this knowledge and we have 600-some athletes, why not include that as part of their development,” Wardenaar said.

Cool the Fork, the first study to be conducted by the Athleat Field Lab, arose out of nutrition grad student and Pennsylvania native Stephanie Olzinski’s hypothesis that athletes in Arizona must have higher levels of dehydration after exercising outdoors than they would after exercising indoors, even in comparable temperatures, because of exposure to sun radiation.

Olzinski received a $3,500 athletics research grant from the ASU Graduate and Professional Student Association to help fund the study.

Working with the ASU women’s soccer team, Wardenaar, Olzinski and a team of nutrition undergraduates measured the athletes’ hydration status at three separate practices where conditions — such as sun radiation and temperature — varied:

• Outdoors, on a sunny day in early March, with a rough temperature of 55 degrees Fahrenheit.

• Inside the climate-controlled Verde Dickey Dome in late March, with a rough temperature of 66 degrees Fahrenheit.

• Outdoors, on a sunny day in mid-April, with a rough temperature of 68 degrees Fahrenheit.

“We really wanted to make it as easy as possible for the athletes and coaches, so we went to their practices; we didn’t schedule anything separate from what they were already doing,” Olzinski said.

Before and after each practice, researchers weighed the athletes after they had completely emptied their bladders, then measured urine specific gravity levels (USG) in their urine to determine their hydration status.

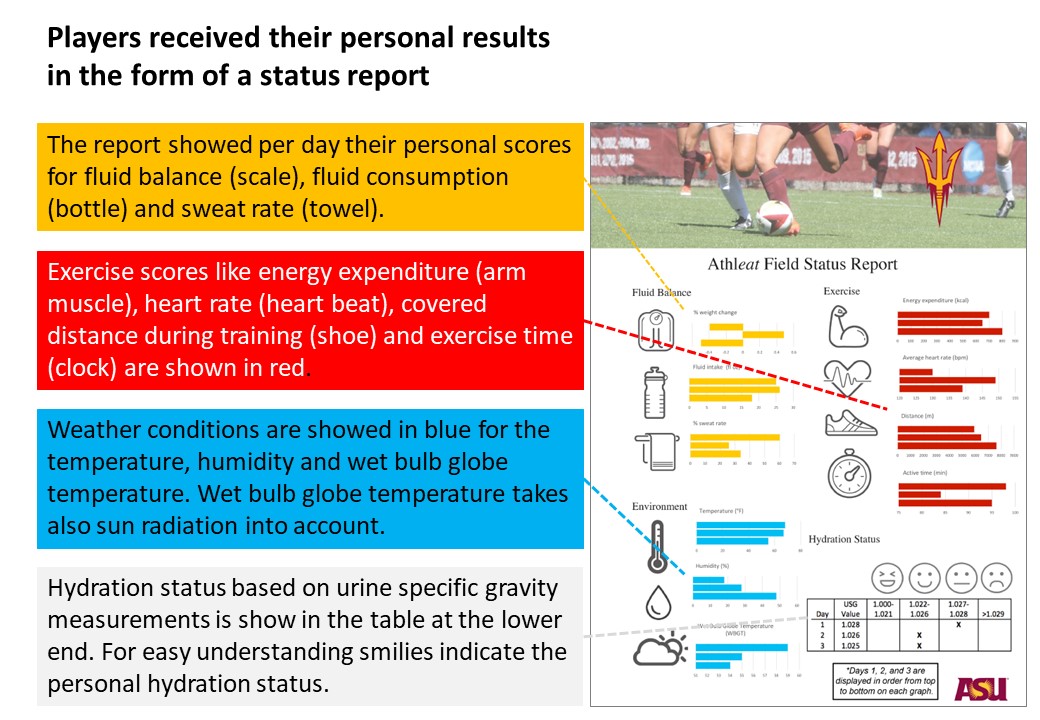

An example of the data provided to particpants in their personalized Athleat Field Lab report. Courtesy Floris Wardenaar

If Olzinski’s hypothesis was correct, the days the athletes trained outdoors in the sun should have resulted in greater weight losses and higher values of USG after practice compared with before practice.

In this instance, the researchers found that the athletes actually weighed slightly more and their hydration status was fairly similar after their outdoor practices compared to just before practice began. However, Wardenaar said that doesn’t necessarily mean they didn’t experience higher levels of dehydration due to sun radiation exposure; it just means they were adequately replenishing their fluids.

Perhaps more telling was the athletes’ level of perspiration.

“We did see greater sweat losses on the third day, which was the day of the highest sun radiation,” Olzinski said. “So even though the athletes were replenishing their fluids well, their sweat rate on that day was the highest, and I think that can be attributed to the increased levels of sun radiation.”

The team attributes the lack of a significant difference between the athletes’ before-practice and after-practice hydration measurements to the fact that even on the hottest day, the temperature was still moderate by Arizona’s standards. They hope to follow up on this study in the near future when temperatures are higher, and expect to see results more in line with Olzinski’s original hypothesis. All they need is another willing team.

“We can say that on moderate days, in 55 or 68 degree Fahrenheit temperatures, if you have enough breaks and drink enough fluids, you are probably OK,” Wardenaar said. “We can predict that at higher temperatures athletes will sweat more, but we are specifically interested in the effect of sun radiation in comparison to the high ambient temperature alone.

“We can predict that athletes will lose more fluid when directly in the sun versus being in the shade, and I think we see a trend in our data that when sun radiation is increased, people show higher sweat loss. We need more data to prove that but at least under moderate circumstances, the trend is going in the direction we expected.”

Other variables the researchers tested include hydration status’ effect on performance and whether consuming water versus a zero-calorie sports drink made a difference in hydration status.

During the practices, athletes wore a device that measured their breathing, heart rate and energy expenditure, and were given the choice of consuming POWERADE Zero or plain water. Further analysis is needed to determine if there is any relationship between those factors.

Cool the Fork is set up as a long-running study in which Wardenaar hopes to engage several different groups of nutrition students and athletics teams to build a more robust data set that can compare differences between teams, seasons and more. And after every study, each athlete receives a personalized report which they can use to help improve their game.

“The individual results give the athletes an opportunity to see how they perform under certain circumstances and set themselves up for better performance,” Olzinski said.

Top photo: ASU women's soccer players practice as the sun sets. Photo by Sun Devil Athletics

More Health and medicine

New study seeks to combat national kidney shortage, improve availability for organ transplants

Chronic kidney disease affects one in seven adults in the United States. For two in 1,000 Americans, this disease will advance to kidney failure.End-stage renal failure has two primary…

New initiative aims to make nursing degrees more accessible

Isabella Koklys is graduating in December, so she won’t be one of the students using the Edson College of Nursing and Health Innovation's mobile simulation unit that was launched Wednesday at Arizona…

Reducing waste in medical settings

Health care saves lives, but at what cost? Current health care practices might be creating a large carbon footprint, according to ASU Online student Dr. Michele Domico, who says a healthier…