An international team of researchers, including Alejandra Ortiz, a postdoctoral researcher with Arizona State University's Institute of Human Origins, has discovered a new genus and species in an unusual place — a tomb.

The Junzi imperialis, an ape that lived in China as recently as 2,200 years ago, was discovered in what was the ancient capital of Chang’an (now Xi’an) in the high-status tomb of Lady Xia, which contained 12 pits with animal remains and other grave goods.

Buried during China’s late Warring States period (475–221 B.C.), Lady Xia was the grandmother of China’s famous first emperor Qin Shi Huang (259–210 B.C.), who not only created a unified imperial system that lasted until the early 1900s, but also commissioned ambitious projects such as the Terracotta Army and the Great Wall of China.

A Chinese painting of gibbons at play. Public domain image

Excavated in 2004, the tomb’s “K12” pit included the skeletons of leopard, lynx, black bear, crane and other birds, domestic mammals and a gibbon. Gibbons and siamangs are small-bodied apes from East and Southeast Asia and, together with the great apes — chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas and orangutans — are humans' closest living relatives.

Today, all species of living apes are threatened with extinction due to human activity and habitat loss. Yet it has generally been believed that prior to the industrial age, ape diversity had not been depleted by human pressures. The well-preserved partial skull of Lady Xia’s gibbon challenges this view, according to a new study published this week in Science.

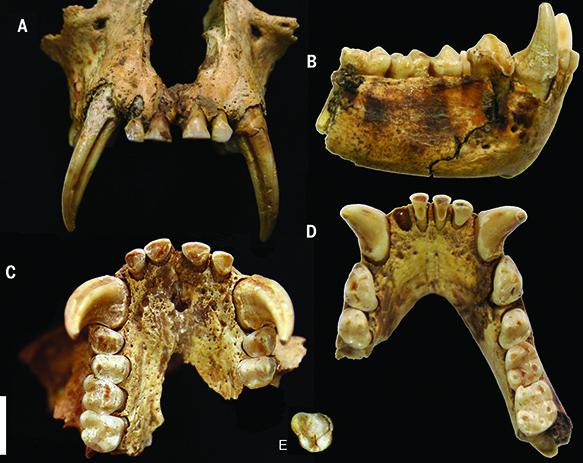

The analysis of Lady Xia’s gibbon and its comparison with present-day gibbons and the extinct Bunopithecus gibbon point to the presence of a new genus and species of gibbon named Junzi imperialis. The Junzi gibbon lived until about 2,200 years ago in central China, more than 1,200 kilometers from the nearest living gibbon populations.

“Although it is earlier in age, Bunopithecus was also found in central China, so at first I thought that Bunopithecus and Lady Xia’s gibbon could have been closely related,” said Ortiz, a co-author of the study.

“But as soon as I looked at its skull and teeth, I knew there was something different about Lady Xia’s gibbon,” she said. Ortiz performed the morphological or shape-and-metric analysis of its dentition and has also previously examined the Bunopithecus skeleton.

Indeed, skull and teeth analyses revealed the form and comparative distinctiveness of Junzi from Bunopithecus and all living gibbon genera.

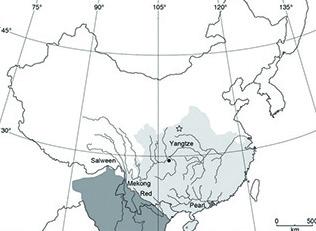

Map of distribution of gibbons in China. The dark gray is the modern distribution of gibbons, and the light gray represents the historical distribution across China. The star indicates the location of the tomb, and the circle is the collection area for the Bunopithecus. Image courtesy of Samuel Turvey

The study represents the first documented postglacial extinction of an ape and of any continental primate. Until relatively recently, the Holocene epoch, which essentially spans the last 12,000 years, was a period of climatic stability. Given the high population density and incidental extensive deforestation experienced for millennia in central China, it is very likely that Junzi became extinct as a result of human impacts and pressures on the environment.

Junzi’s discovery and evidence from historical accounts suggest that past human-caused loss of apes and other primates may have been underestimated.

“This points to the need for more studies to better understand primate vulnerability in order to increase conservation efforts and help prevent future extinctions of our closest living relatives before it is too late,” Ortiz said.

Cranium and mandible of Junzi imperialis: (A) lower cranium, (B) mandible, (C) upper teeth, (D) lower teeth, (E) individual tooth. Image courtesy Samuel Turvey.

Top photo: A modern-day gibbon hangs out in a tree. Image courtesy of Pixabay

More Science and technology

Google grant creates AI research paths for underserved students

Top tech companies like Google say they are eager to encourage women and members of historically underrepresented groups to consider careers in computer science research.The dawn of the era of…

Cracking the code of online computer science clubs

Experts believe that involvement in college clubs and organizations increases student retention and helps learners build valuable social relationships. There are tons of such clubs on ASU's campuses…

Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes celebrates 25 years

For Arizona State University's Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes (CSPO), recognizing the past is just as important as designing the future. The consortium marked 25 years in Washington, D…