It’s remarkable choreography: In each of our bodies, more than 37 trillion cells tightly coordinate with other cells to organize into the numerous tissues and organs that make us tick.

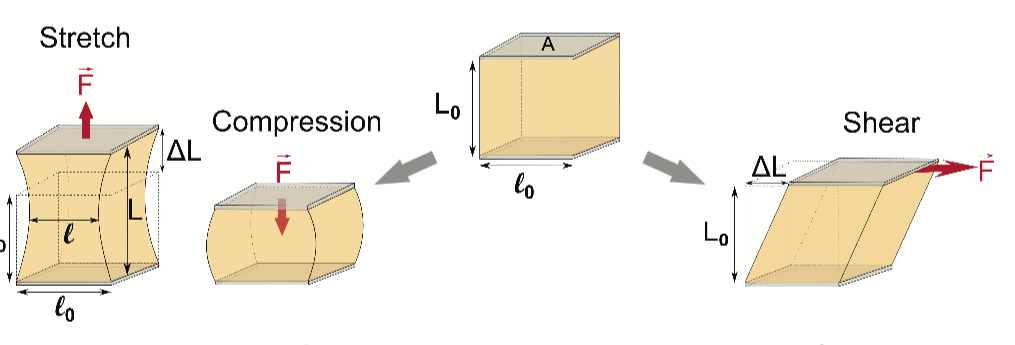

The body's cells are subjected to all sorts of environments and forces over a lifespan, calling for methods to quantify mechanical properties of cells and tissues.

“A few years ago, the (National Cancer Institute) initiated this challenge within the framework of the Physical Sciences in Oncology (PSOC) Network, and several labs in the U.S. and Europe were invited to participate,” said Arizona State University researcher Robert Ros (pictured above), director of Arizona State University’s Center for Biological Physics and a faculty member in the Department of Physics and the Biodesign Institute’s Center for Single Molecule Biophysics.

Ros is an expert within an emerging science devoted toward a better understanding of the routine mechanical and physical forces cells may be subjected to in the body.

These forces include cells rafting through river-rapid-like currents of circulating blood or mosh-pit clumps of crowded neighbor cells within tissues and organs that all serve to bend, push, compress, shear or deform them.

By applying a total of six different technologies, ASU scientists could bend, push, twist and stretch cells in ways similar to what they may encounter within the body.

And so, an international team made up of researchers from eight different labs got to work, including ASU (Ros and graduate students Jack Staunton and Bryant Doss), Johns Hopkins University, University of Pennsylvania, Tufts University, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the National Cancer Institute, the University of Paris-Diderot, and the Technical University of Dresden and Saarland University, both in Germany.

Together, they rolled up their sleeves to better understand the physical forces and how best to optimize available technology. They wanted to compare different common techniques and understand the differences in the results of those techniques.

The force within us

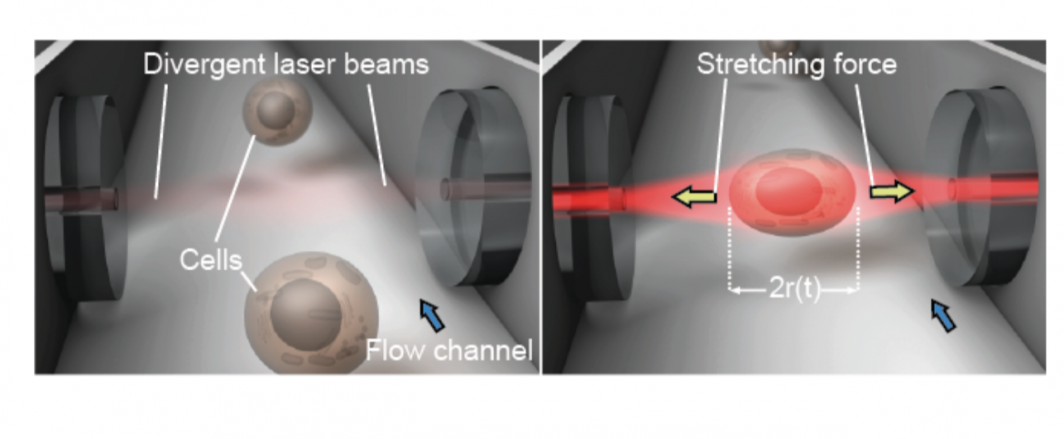

In the study, the team focused on measuring the stiffness, bending, twisting and viscosity of individual cells — focused on a breast-cancer cell line — using all of the most state-of-the art technology at their disposal.

How both healthy and cancerous cells respond to this environment — and whether there are key differences that can be identified for future diagnostic applications — was of keen interest to both the NCI and the physicists taking on the NCI’s challenge.

“All labs received from NCI the same cells (known as MCF-7 breast-cancer cells), and we agreed on similar conditions for the measurements,” said Ros.

But before making their measurements, they first had to ensure that all the subtle conditions of growing cells in the lab were the same, including temperature, acidity of the solution or how long they had been growing.

“We obtained the measurements from a total of six techniques in eight different laboratories using the same breast cells from the same lot, cultured in the same medium from the same lot, all directly provided by the same tissue-culture cell bank,” said Ros.

The research team employed different technologies to apply mechanical forces to the cells across a number of scales, from inside a cell to whole cells to a single cell layer. Also important to the team was how fast they could make the measurements, which varied from processing a few cells to more than 2,000 every hour.

More to the surface

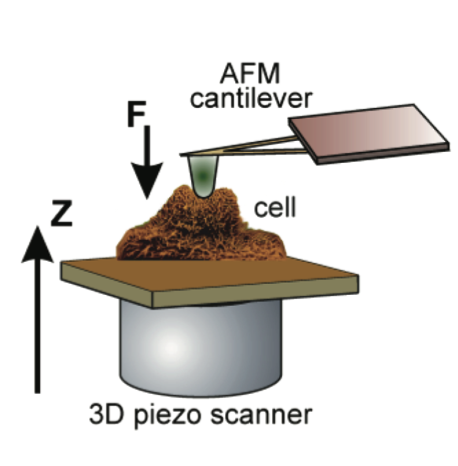

Three of these groups, including Ros’, focused on an instrument to make cell mechanical measurements that often represents the eyes of nanotechnology, called atomic force microscopy (AFM).

AFMs are a commercially available tool widely used in nanotechnology, and fairly easy to use.

AFMs are so sensitive, they can see down to the level of individual atoms, and for the study, the mechanical forces within the cell. An AFM probe, which is like a record player arm and a type of cone-shaped needle, can apply a force on the surface of a single cell and measure the deformation.

Ros’ focused on Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM). AFMs are so sensitive, they can see down to the level of individual atoms.

The probes can be interchanged to measure the cellular forces at different scales.

“Overall, our results highlighted how mechanical properties of cells can vary by orders of magnitude, depending on the length scale at which cell viscoelasticity is probed, from tens of nanometers (e.g., the diameter of an AFM tip) to several micrometers (the size of a whole cell),” said Ros.

“Our measurement with a nanoscale AFM probe showed that the mechanical properties of cells are heterogeneous and vary considerably at a single cell and from cell to cell,” said Ros. “Together, these results show that the mechanical properties of cells measured by AFM can differ more than tenfold, depending on the measurement parameters and the probed regions of the cells, as well as the dimension of the indenter.”

Going with the flow

By applying a total of six different technologies, they could bend, push, twist and stretch cells in ways similar to what they may encounter within the body.

In addition to ASU’s AFM technology, this also included an alphabet soup of technology: magnetic twisting cytometry (MTC), particle-tracking microrheology (PTM), parallel-plate rheometry (PPR), cell monolayer rheology (CMR) and optical stretching (OS).

They were particularly encouraged when they saw similar results for each of the different techniques.

In addition, their latest results helped confirm data from previous studies, crossing an important scientific verification step — that the measurements could be duplicated.

Opening new avenues

Moving forward, of interest to Ros’ group is measuring these cellular mechanical forces within 3D cell-culture environments that can better mimic cells within the body.

“With this study, we’ve laid the groundwork that our results are more likely to be due to the differential mechanical responses of cells to the different force profiles produced by these different methods, rather than just random errors,” said Ros.

They will continue to explore different types of cells in different environments to see if there is a mechanical force that can be a new type of cell “signature” that may lead to a brand new type of diagnostic tool.

Top photo: ASU researcher Robert Ros is director of ASU’s Center for Biological Physics and a faculty in the Department of Physics and the Biodesign Institute’s Center for Single Molecule Biophysics. Ros is an expert within an emerging science devoted toward a better understanding of the routine mechanical and physical forces cells may be subjected to in the body. Photo by Biodesign Institute

More Science and technology

Indigenous geneticists build unprecedented research community at ASU

When Krystal Tsosie (Diné) was an undergraduate at Arizona State University, there were no Indigenous faculty she could look to in any science department. In 2022, after getting her PhD in genomics…

Pioneering professor of cultural evolution pens essays for leading academic journals

When Robert Boyd wrote his 1985 book “Culture and the Evolutionary Process,” cultural evolution was not considered a true scientific topic. But over the past half-century, human culture and cultural…

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would become one of the most famous fossil skeletons of our lifetime — the 3.2…