Editor's note: This story is being highlighted in ASU Now's year in review. Read more top stories from 2018 here.

In 1799, soldiers of Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign were knocking down walls to build a fort near the city of Rosetta when they found a large basalt slab inscribed with strange symbols. In 1820, a peasant searching for marble building blocks on the Greek island of Melos uncovered the statue of an armless woman. In 1974, Chinese farmers digging a well near the city of Xian unearthed 8,000 life-size terra-cotta soldiers, horses and chariots.

The Rosetta Stone; the Venus de Milo; the Xian Terra-cotta Army — priceless relics of the past, each imbued with a unique historical significance.

More recently, in October 2015, an international group of scholars visiting a monastery in Altomuenster, Germany, were unexpectedly granted entrée to its usually off-limits library. Inside was a treasure trove of texts and artifacts belonging to the unconventional Brigittine Order of Catholic nuns, dating from the 15th century to present day.

“You never think you’re going to discover an unknown library ever in your career,” said Corine Schleif, Arizona State University professor of art history. She and Volker Schier, a musicologist and visiting faculty at the Institute for Humanities Research, were leading the fortuitous scholars on a tour of European women’s monasteries.

The Altomuenster monastery, just northwest of Munich, was their last stop.

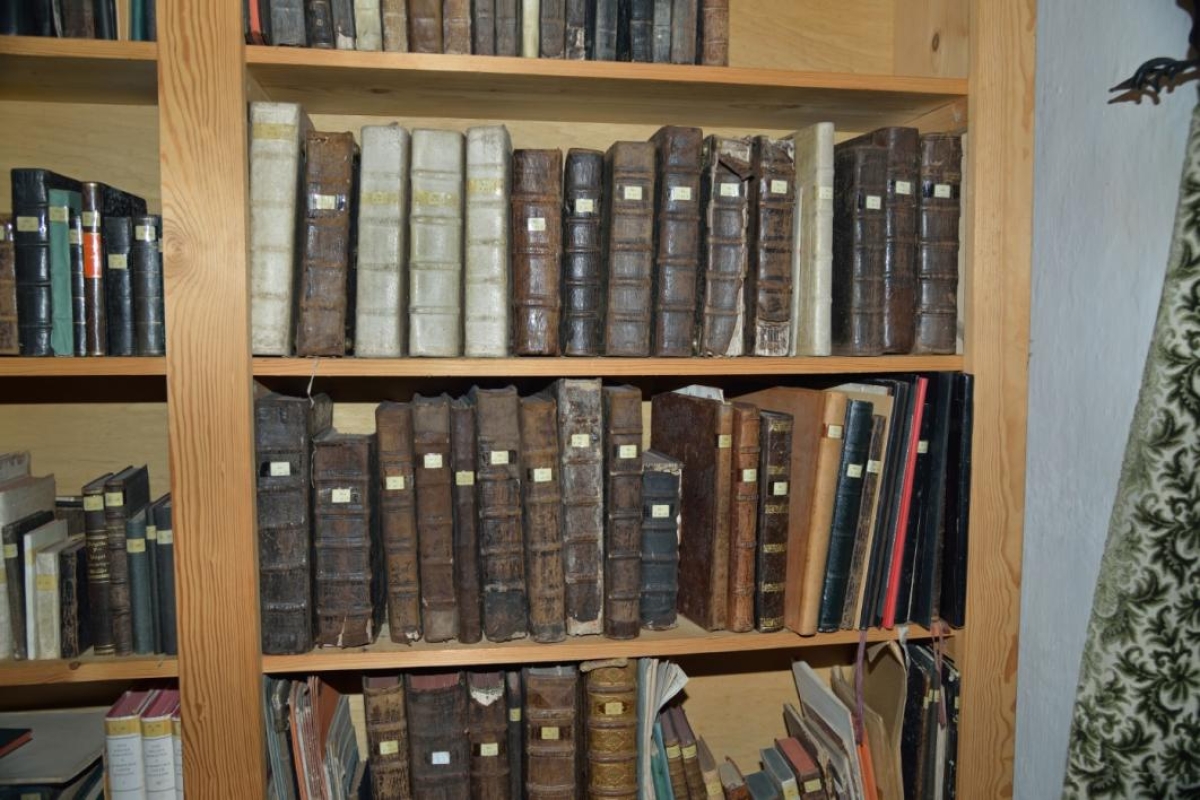

Left undisturbed for 500 years, the library contained over a thousand previously unknown manuscripts, as well as works of art and devotional objects. If it had belonged to another order, such as the Benedictines or Franciscans, about whom a great deal is already known, it probably wouldn’t have been as monumental a find.

“For the Brigittines,” Schier said, “it more than doubles the number of known manuscripts.”

Immediately recognizing the magnitude of the discovery but with impending flights back to their countries of origin, the group vowed to return at a later date and properly delve into the bounty. A month later, a proclamation came from the Vatican that the monastery was to be permanently shuttered.

“We assumed we could go back any time, that there was no immediate rush,” Schleif said. “Then when they closed the monastery we became very concerned.”

The location of the monastery, in the suburbs of Munich at the end of a commuter rail line, means real estate there is at a premium. Many older buildings have been converted into luxury housing to capitalize on the area’s popularity. Once it was announced that the monastery would be closed, Schleif and Schier feared it would succumb to the same fate, and the precious artifacts inside cast heedlessly asunder.

“You can only turn a monastery into condos if it’s empty,” Schier said.

Alarmed at the sheer volume of historical knowledge that stood to be lost if the ancient texts were split up and sold off to private buyers, or worse, thrown in a landfill, he and Schleif sprang into action. At first, they appealed to the papal commissar in Munich, offering to write a grant and secure funds to catalogue and digitize the collection.

Their offer was denied.

“They kept saying that they didn’t have any valuable books there,” Schleif said. “We had seen enough of them that we knew they were very valuable. They had more Brigittine texts than the whole rest of the world.”

So they went higher up the chain of command, writing a letter to Cardinal Reinhard Marx, the Archbishop of Munich and Freising, and had it signed by all the scholars in their tour group — including the late Tore Nyberg, a well-known Swedish professor and influential historian, whose clout they hoped might sway the church.

But still, nothing.

Once again, Schleif and Schier upped the ante. They drafted an online petition that garnered roughly 2,500 signatures from experts in fields as diverse as anthropology, literature and religious studies, who all agreed the Altomuenster library was a rare and invaluable find.

Adding to the pressure, several news outlets had gotten wind of the story and began sniffing around the monastery, where they were met with a less-than-warm reception. According to Schleif, one representative of the church told an Associated Press reporter something along the lines of: “We don’t need Americans telling us what to do with our cultural heritage; we have been at it much longer than they have.”

“So somehow our whole group — through me — became American,” Schleif said. Aside from her, the group of scholars included Schier, who is German, as well as citizens from such countries as Sweden, Finland and the Netherlands.

“That was kind of hard to take,” Schleif said. “This notion of ownership. That historical and cultural artifacts don’t belong to all of us.

“I feel really strongly that [for example] my African-American PhD student should not have to work [only] on African-American art. … Or a Native American student at ASU shouldn’t have to work [only] on Native American art. If we want to talk about global history and global culture and ‘worlding,’ as the new term is, then we have to find ways of practicing that.”

“What we are interested in as scholars is world cultural heritage,” Schier added, “and this is clearly world cultural heritage. Anybody on this planet should have the possibility to enjoy it, to see it, to study it, to work on it.”

The Altomuenster texts provide an excellent opportunity to study women’s history, in particular. The Brigittines were founded in 1344 by Saint Bridget of Sweden, who had a distinct vision for the order — one that gave women the upper hand. Whereas other orders were still presided over by men, Brigittine monasteries were entirely under the rule of an abbess.

“Women ran this institution for hundreds of years,” Schleif said. During the Middle Ages, that was no small feat. At the time, one of the only acceptable alternatives to marriage was to become a nun, and the Brigittines gave the women in their order the autonomy to make their own decisions, especially in financial matters.

One Brigittine Schleif and Schier learned of through letters recovered from the monastery was a widow who had entered into the order (one of the only ones to allow widows) upon her husband’s death in order to maintain control of her self-made fortune. As a Brigittine, she was able to use her wealth and influence to improve the lives of other women in the order.

“They were responsible for their own destiny, until right now,” Schleif said, alluding to the state of affairs the order finds itself in today; the reason behind the Vatican’s decision to close the Altomuenster monastery for good — presently, the Brigitine order counts just a handful of members. Both Schleif and Schier agree it’s on its last legs and that its impending demise only underscores the urgency to preserve the library and related artifacts.

“As an institution in the Middle Ages and beyond, where women had the option [to be autonomous] … we certainly want to keep documentation of that,” Schleif said.

The petition had been the tipping point. Soon after it went viral, Schleif and Schier received an email inviting them to come view the manuscripts at the diocesan archives in Munich, where they had been moved following the announcement of the monastery’s closing.

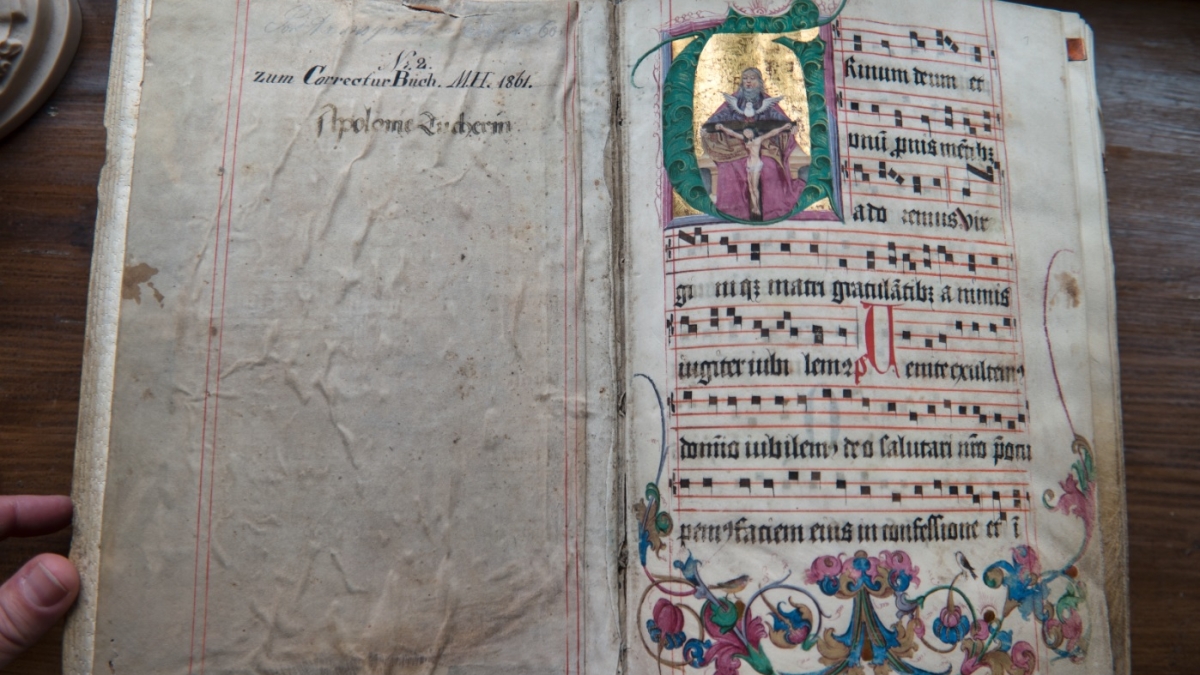

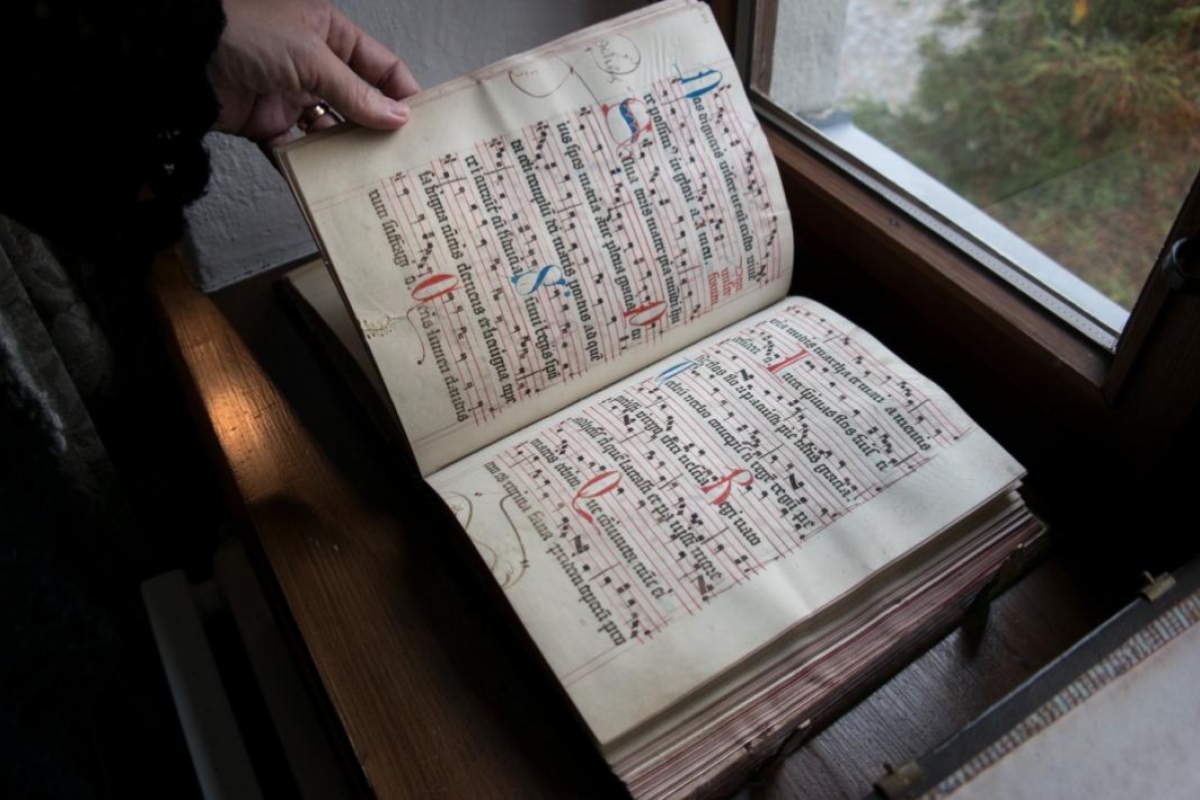

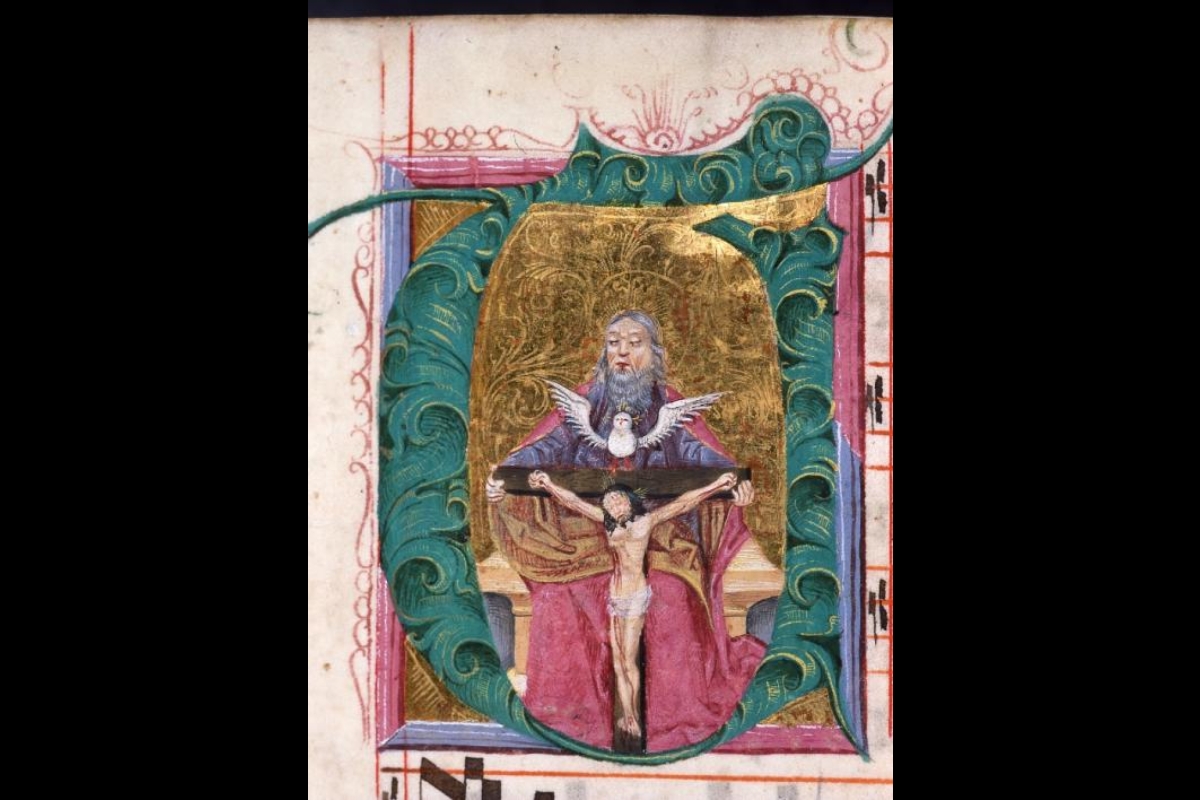

Over three days during the summer of 2017, Schleif, Schier and a third colleague sorted through towering stacks of dusty, weathered tomes, flipping the embrittled pages with diligence and alacrity. It wasn’t long before the treasures began to surface: a meticulous, hand-written card catalogue of the entire library, which proved exceptionally accurate and immensely helpful; processionals whose margins had been curiously torn away; and page after page of brilliantly colored illustrations.

Eventually, Schleif, Schier and their interdisciplinary group of scholars — including musicologists, historians and computer scientists — hope to use the texts to create a virtual reconstruction of a medieval church, where one can become immersed in the experience whilst listening to the songs that were sung, reading the prayer books and looking around at the architectural elements and fellow congregants, nuns and priests in period-appropriate dress.

They’ve titled the project Extraordinary Sensescapes. Their hope is that the combined effect of visual details and acoustics will transport users to another point in time.

“It’s important that we are able to empathize with each other and that we’re able to think ourselves into situations that are so vastly different from our own,” Schleif said. “And if we go back into history, maybe we can do it in a way that’s nonthreatening because we have analytical distance, and apply it to our own situations today.”

They’ll need to digitize whatever manuscripts from the Altomuenster library they intend to use for the project, and ideally they would like to digitize the entire library to make it accessible to scholars everywhere. However, both Schleif and Schier agree the need to protect the physical texts themselves is just as crucial because of what we can learn from the material elements.

“It wouldn’t be enough to digitize them,” Schier said. “A photo can never show you the real colors. It jumps at you. But it’s not only the colors that you can’t digitize, it’s also the utmost detail, down to every little brushstroke.”

And every little torn margin. He and Schleif presume that the margins torn out of the processionals may have been used to stiffen the fabric of the Brigittines’ distinctive crowns, which are composed of several white strips fastened with five red dots depicting the wounds of Christ.

“That gives you an idea of how important the material is,” Schleif said. “These things tell stories. It’s not just about the text. You really do want to touch it and look at it carefully. These books were put in oxcarts and traveled through Europe. Each book has its own history, if it could only talk.”

Thanks to the efforts of Schleif, Schier and their colleagues, those histories will continue to be shared, now that the library is safely housed at the diocesan archives.

“I see it as one of the major successes of my career, and [a major success for] ASU, actually,” Schleif said. “We’ve preserved world cultural heritage, even though we’re so far away. I think our interests should go beyond the desert, to the rest of the world, too.”

Another win for the scholars is the fact that the Altomuenster manuscripts are being kept as an ensemble. Often, through accidents of preservation, collections of texts become irrevocably separated as books are lost, sold or thrown out, leaving scholars with the task of piecing together and trying to make sense of what remains.

“Here, we have this intact library,” Schleif said. One that serves as an uninterrupted historical account of the life and culture of the Brigittines from 1496, when the Altomuenster monastery was built, to present day.

The future of the nonliterary items that filled the monastery remains uncertain. Schleif and Schier witnessed their removal from the monastery vicariously, through photos taken and sent to them by one of the last nuns still residing there. They described the manner in which centuries-old habits, altars, crucifixes and statues were handled and transported as “appalling”: roughly packed into ordinary moving trucks without protection. And they’re still unsure as to where the items ended up.

That, however, is a mantle they hope a more suited champion will assume.

“If one fights, one has to try to succeed. And we were happy that we could succeed [where the library was concerned],” Schier said. “But we thought that perhaps another scholar might take up the fight for the other objects. And they’re worthwhile to fight for. Somebody working in the 18th or 19th century … for them, this is El Dorado.”

Looking back on the ordeal, it’s no question Schleif and Schier would do it all over again if they had to.

“We are scholars. We have to pipe up if we see important cultural heritage endangered,” Schier said. “This is our responsibility, and we have to make it known and take on necessary actions.”

Top photo: Liturgical manuscript dated 1486, probably written in Nuremberg and brought to Altomuenster by the founding sisters from the monastery of Maihingen. Photo by Volker Schier

More Arts, humanities and education

Local traffic boxes get a colorful makeover

A team of Arizona State University students recently helped transform bland, beige traffic boxes in Chandler into colorful works of public art. “It’s amazing,” said ASU student Sarai…

2 ASU professors, alumnus named 2025 Guggenheim Fellows

Two Arizona State University professors and a university alumnus have been named 2025 Guggenheim Fellows.Regents Professor Sir Jonathan Bate, English Professor of Practice Larissa Fasthorse and…

No argument: ASU-led project improves high school students' writing skills

Students in the freshman English class at Phoenix Trevor G. Browne High School often pop the question to teacher Rocio Rivas.No, not that one.This one:“How is this going to help me?”When Rivas…