By all accounts, Israel del Toro should have died from the pressure-plate landmine that exploded under his military vehicle in eastern Afghanistan in December 2005.

He suffered third-degree burns over 80 percent of his body. He lost just about all his fingers. He was in a coma for three months. His odds of survival were dire. Even if he lived, he would be immensely debilitated. Yet, today he walks among us. Laughs. Runs. Talks. Inspires.

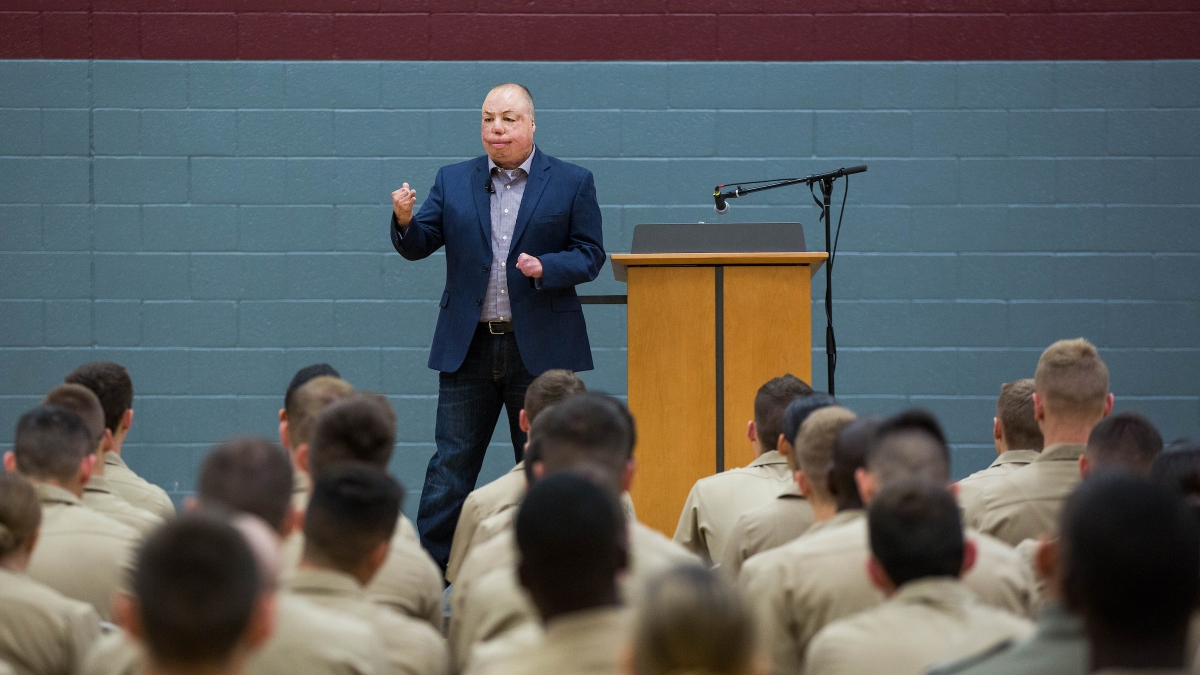

On Friday, Del Toro, a U.S. Air Force senior master sergeant, visited Arizona State University as the inaugural guest under the Pat Tillman Veterans Center's new “In the Spirit of Pat” speaker series.

“The speaker series is an opportunity for the ASU military and veteran community to engage with remarkable individuals who will speak on themes of achievement, openness, adventure, love and service,” said Michelle Loposky, Pat Tillman Veterans Center assistant director for outreach and engagement.

The plan is for the speaker series to be an annual event just before Pat’s Run in April, Loposky said. But the goal is to make it biannual by also inviting a speaker during ASU’s Salute to Service celebration in November.

“‘In the Spirit of Pat’ is about individuals who are doing extraordinary things, just as Pat Tillman did,” Loposky said. “The hope is that it will inspire our student veterans and others to do the same.”

Del Toro did an extraordinary thing: He survived something that would have killed most.

He was an Air Force Tactical Air Control Party member, referred to in military circles as a TACP (pronounced “tack p”). They are a small, elite team of airmen often embedded in Army units, whose responsibilities include locating enemy forces and radioing in airstrikes against them.

On Friday, Del Toro told his story of survival and perseverance during separate speaking engagements on the Tempe campus with ROTC students, student veterans, faculty and staff.

Growing up a Hispanic kid on the south side of Chicago was a tough life in general. His was even tougher. He lost his father at age 12, and a year later his mother passed away.

Del Toro did not join the military right away. He attended the University of Illinois for two years but nearly dropped out his freshmen year after his grandfather suffered a stroke. But his grandmother would not allow it. It wasn’t until she was diagnosed with cancer his sophomore year that Del Toro knew that as the oldest child he had to leave college to help his grandparents take care of his two younger sisters and brother.

Although he had a decent job at the time, Del Toro was looking for more. So he met with an Air Force recruiter after a recruiting commercial on TV caught his attention. His fate was sealed. He graduated from basic training in 1993 and was accepted into the TACP program.

It wasn’t an easy road. He questioned himself one night in the Florida wilderness during TACP night land navigation training — a graduation requirement.

“I got to the point, on the third time of night nav, where I’m literally crawling on my hands and knees with my rucksack, my radio, my weapon, and I’m saying, ‘Why am I going through this crap?’” Del Toro said. “I’m 22 freaking years old; I don’t need this.”

But the words of his dying father reverberated in his head: “Take care of your family.” Del Toro knew that joining the military wasn’t just about him but about continuing to financially help his family.

“So I sat down, relaxed, probably said a little prayer … and I made it, and I graduated,” Del Toro said. “Got my beret and headed off to my next set of schools.”

Del Toro would go on to deploy to Bosnia and Iraq before landing at Forward Operating Base Lagman in Afghanistan’s Zabul province in August 2005.

Up until Afghanistan, Del Toro’s life had been a series of ups and downs, he said. Just when everything seemed great, something bad would happen. The death of his parents. Death of a cousin, who was like a brother to him. Death of his grandmother. Death of one of his troops in combat.

“For a long time I felt like I was cursed,” Del Toro said. “Every time I was at a high, I got knocked down. Maybe God was getting me ready for the biggest obstacle in my life.”

On Dec. 4, 2005, Del Toro was out with an Army scout team searching for a “high-value target” in Afghanistan. As his vehicle crossed a creek Del Toro felt immense heat on the left side of his body and realized “Holy crap, I just got hit.” He never believed the notion of people’s lives flashing before their eyes.

“But when I got hit, it was crazy, it was like flash, flash, flash, then it stopped,” said Del Toro, as three distinct goals he had hoped to accomplish flashed through his mind — marrying his wife through the church, honeymooning in Greece and teaching his son how to play ball.

Del Toro ran out of his vehicle on fire from head to toe. The flames overtook him and he dropped. Lying there thinking he was about to die, he lamented breaking the promise to his wife that he would come back and the promise to his son that he would not let him grow up without a father.

“But worst of all I broke the promise to my dad that I would always take care of my family,” he said.

His teammates wouldn’t have it. One of them picked him up, threw dirt on him, and jumped in the creek with him after Del Toro inadvertently set him on fire as well.

Once Del Toro made it back to his base and was under medical care, he finally closed his eyes and did something he had wanted to do since right after he was “blown up,” but his teammates wouldn’t let him — sleep. That was Dec. 4. He would not wake up until March.

Doctors gave him a 15 percent chance to live. When in the hospital, his wife received urgent calls on three separate occasions because they thought death was upon him. But even if he survived, doctors were skeptical that he would be able to walk or live without a respirator.

Del Toro defied the odds through sheer grit and determination as he endured some of the worst pain possible on the road to recovery.

“The doctors literally skin you alive,” Del Toro said. “What is going to kill you is an infection, not a bullet, not burns … so if you are a burnt person, the doctors have to skin you alive so you don’t get an infection.”

Del Toro’s doctors think his recovery was like a miracle. But behind the “miracle” was his determination to be there for his family, to keep promises he made and to stay in the military. He is in fact the only 100 percent disabled military member ever allowed to remain on active duty with the Air Force, and he is now assigned to the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs serving as an instructor with Wings of Blue — the United State Air Force Parachute Team.

“Find that fire from inside of you,” Del Toro said. “We all have it. We all have that thing that drives us. For me it was my son. That was my fire. It drove me, it pushed me.”

Today, the 42-year-old walks, runs, jumps out of airplanes and competes in track and field events. He won the Pat Tillman Award for Service ESPY in 2017. He has met presidents and British royalty and is even good friends with former "Daily Show" host Jon Stewart. But what means most to him is helping others.

“I know I may not touch everyone in the world,” he said. “But if I can touch that one person that is really down and thinking there’s nothing left in life, not worth fighting for … that they hear my speech and hear what I went through and how I didn’t give up, how I kept fighting, and it inspires you to keep pushing, then all that pain, all that suffering I went through my entire life is worth it, because I helped that one person.

“That is the role for any human, to make things better for those who follow.”

Top photo: Air Force Senior Master Sgt. Israel del Toro speaks to ASU students about his military enlistment, career and life following his recovery from third-degree burns after being wounded in Afghanistan, at the Sun Devil Fitness Center on Tempe campus on April 20. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

More Sun Devil community

University Archives chronicles more than 140 years of Sun Devil history

Editor’s note: This is part of a monthly series spotlighting ASU Library’s special collections throughout 2024.What was the name of the butcher who bequeathed the first piece of land that…

3 outstanding ASU alumni named The College Leaders of 2024

Three outstanding Arizona State University alumni from The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences will be named as this year’s slate of The College Leaders. The honor recognizes alumni for their…

From mushy ice to Mullett Arena

Greg Powers rubbed the top of his head and smiled.Powers, Arizona State University’s hockey coach, had been asked to reflect on the 10th anniversary of ASU hockey becoming an NCAA Division I program…