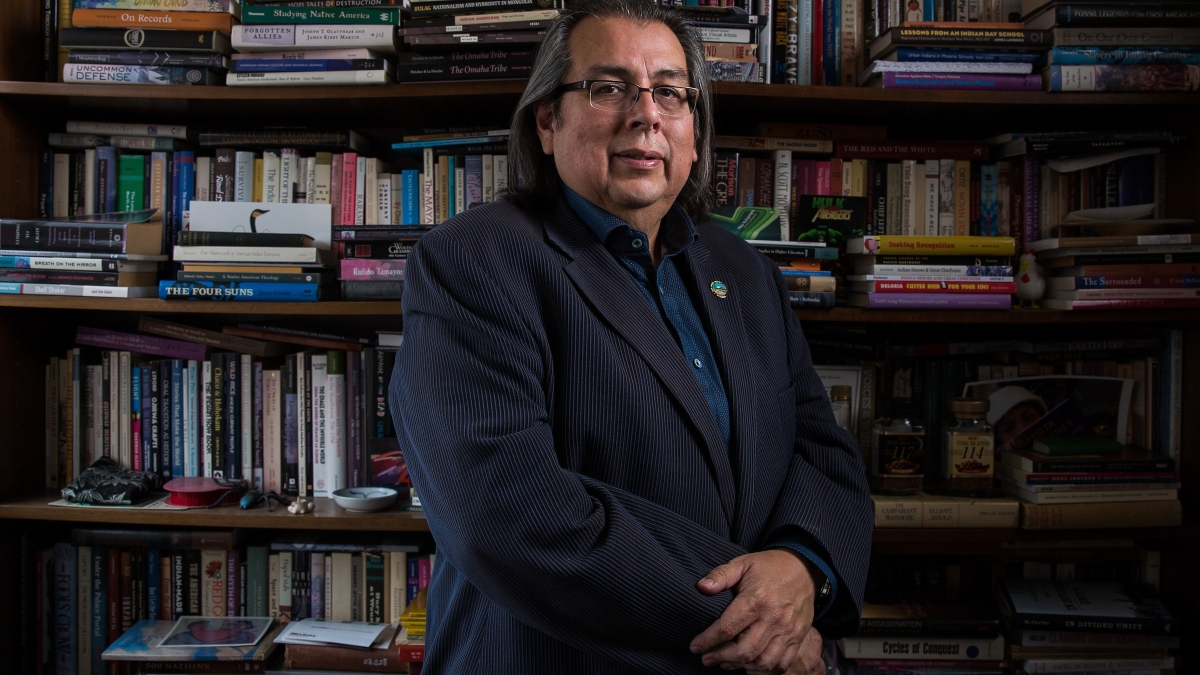

If you want to know something about scholarly activism and indigenous communities, the office of David Martinez would be a good place to start.

It’s the collective home of every book ever nominated for the Labriola Center American Indian National Book Award, now in its 10th year. (Check out a full list of Labriola book award winners.)

As chair of the selection committee, MartinezAkimel O’odham, Hia Ced O’odham, Mexican. has literally surrounded himself with a decade’s worth of research — as many as 200 books — by indigenous scholars, Native and non-Native, around issues of environmental justice, sexual violence, historical representation and tribal sovereignty.

“We get anywhere from 12 to 20 nominees each year,” said Martinez, an Arizona State University associate professor of American Indian studies

At the time, there were few book awards within American Indian studies, but this has changed. From year to year, Martinez has seen a notable increase in opportunities for indigenous people-focused projects.

“Now more than ever, American Indian studies is relevant to the national discussion on democracy, which has come under assault. Nobody knows that better than tribal communities who have not always had their voices heard or counted toward policy decisions made on their behalf,” he said. “This is a time to pay attention to those voices.”

On the importance of visiting

Criteria for the Labriola book award emphasizes that the research be developed out of a meaningful relationship with the community on which it’s focused.

“The research must serve some need the community has, as opposed to research for the sake of research,” said Martinez, explaining that the idea stems from “our own intellectual history” — a standard set by Vine Deloria Jr., in his “Indian Manifesto” ("Custer Died For Your Sins," 1969), in which he criticized the social sciences for generating research that didn’t do the communities any good. “His belief was that work on Native communities must also work for Native communities.”

Deloria’s philosophy of socially embedded, use-inspired research — certainly a driving force at ASU — guided the work of Elizabeth Hoover in her 2017 book, "The River is in Us: Fighting Toxics in a Mohawk Community," this year’s winner of the Labriola award.

Elizabeth Hoover

Hoover said the book came out of “kitchen-table conversations” with friends, workers, leaders and scientists in the remarkable upstate New York Mohawk community of Akwesasne, along the St. Lawrence River, who partnered up to develop grass-roots programs aimed at fighting environmental contamination and the threats it posed to their land, health and culture.

“There is something to be said for the importance of visiting and how it can impact a project,” said Hoover, the Manning Assistant Professor of American Studies at Brown University. “These slow-simmering conversations gave me the impetus for wanting to look at these health studies and how people were responding to them. I had friends working in a gardening group who made me want to think more about the impact of food and the way that contamination has these collateral impacts as well, such as concerns over exposure that cause people to avoid food.”

Hoover, the fourth consecutive Native American woman to receive the Labriola book award, says she wants people to find her work useful and for other Native communities to see what Akwesasne has accomplished.

“I want people to have this information and for other people to be inspired by this work, including scientists,” she added. “Some have written me to say they’re thinking about their work in a different way now.”

‘An ongoing awareness’

Martinez said Hoover’s book is an elegant example of a project that brings together the best in indigenous scholarship with the real-world needs of the community.

“Hoover is becoming one of the leading figures on the issues of food sovereignty and environmental justice for American Indians,” he said. “In the next five to 10 years, her work will be as important as Winona LaDuke’s.”

For most people, environmental crises emerged in the 1960s — but from an American Indian perspective, tribes have been deeply concerned about the impact of development on the environment since the first settlers appeared.

“The diverting of rivers and streams, the changing of non-farm land into farm land, the impact of mining and the railroads — Native people have always been alarmed by what’s going on,” Martinez said. “Hoover’s book represents an ongoing awareness among American Indians that the development that has been occurring in their lands since the time of colonialism has been creating this ever-going environmental crisis.”

In the face of such crises, the books that practically spill over the shelves of Martinez’s office are proof of indigenous resilience and, more importantly, resistance.

“It’s one thing to overcome the hardships that come with living in a colonial system,” Martinez said. “It’s another thing for those tribes to enact a political agenda that rebels against power and brings about real change.”

You can learn more about Hoover and her book at a special reception and Q&A session, hosted by ASU Library’s Labriola Center, from 3 to 4:30 p.m. Tuesday, April 24, in C2 of Hayden Library.

Top photo: David Martinez poses for a portrait in his office at Discovery Hall on the Tempe campus. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

More Arts, humanities and education

‘It all started at ASU’: Football player, theater alum makes the big screen

For filmmaker Ben Fritz, everything is about connection, relationships and overcoming expectations. “It’s about seeing people beyond how they see themselves,” he said. “When you create a space…

Lost languages mean lost cultures

By Alyssa Arns and Kristen LaRue-SandlerWhat if your language disappeared?Over the span of human existence, civilizations have come and gone. For many, the absence of written records means we know…

ASU graduate education programs are again ranked among best

Arizona State University’s Mary Lou Fulton College for Teaching and Learning Innovation continues to be one of the best graduate colleges of education in the United States, according to the…