On one of the most memorable days of her life, Kaye Reed found herself holding the jawbone of an ancestor who lived 2.8 million years ago. It was a discovery that changed our understanding of the timeline for the entire human species.

In this few inches of fossilized bone and five teeth was new evidence revealing the existence of human relatives 400,000 years earlier than previously thought. This would be an exciting day for anyone, but for Reed, an anthropologist who studies humans in the past and present and how they live, it was an experience years in the making.

Reed’s team had been visiting the same paleoanthropological field site, with its loose, sandy soil and lack of shade, since 2002. In 2013, Chalachew Seyoum, a graduate student on the team, made the landmark fossil find. The findings were published in Science in 2015.

The discovery of a hominid jawbone by ASU researchers in Ethiopia pushed back the known existence of human relatives by 400,000 years to 2.8 million years ago. Photo credit: John Rowan

Reed is a President’s Professor, director of Arizona State University’s School of Human Evolution and Social Change and research faculty with ASU's Institute of Human Origins. In addition to Seyoum, her team included Chris Campisano, associate professor in the school and research faculty with the institute, and Ramon Arrowsmith, professor in ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration.

The School of Human Evolution and Social Change spans many different fields of anthropology, each investigating different aspects of the human experience. Unlike other anthropology schools, however, it also offers programs in global health and applied math.

“Understanding humans touches all of these things, so you really need to have a faculty who can branch out and connect to all of those and then come back together to share ideas,” Reed said.

At ASU, anthropologists are asking questions across the spectrum of what it means to be human — from the origins of our species, Homo sapiens, to understanding humans today, to how all of this knowledge can help us in the future.

Leader of the pack

This year, ASU was ranked No. 1 for anthropology-related research expenditures in the National Science Foundation’s most recent Higher Education Research and Development survey. At $13.2 million, ASU is far ahead of the pack for anthropology-related research“Research expenditures” is the measure that universities typically use to report and assess the volume of their research activity.. The No. 2 school, the State University of New York at Buffalo, had $5.9 million in anthropology-related expenditures.

ASU’s ranking reflects large research awards that support new approaches to old questions. For example, in 2016, the Institute of Human Origins was awarded a $4.9 million, three-year grant from the Templeton Foundation for the study of human origins. The grant enables ASU researchers to pursue innovative methods, including combining the traditional “bones and stones” research with investigations about human thinking and how it arose. The work on this grant leverages the diverse expertise of ASU faculty and has set the direction of human origins research for years to come.

ASU’s School of Human Evolution and Social Change is home to undergraduate and graduate degree programs in anthropology, global health and applied math as well as graduate degrees in environmental social science and museum studies.

Anthropology research at ASU tops other charts as well. In the most recent assessment from the Center for World University Rankings, ASU is the top school in the U.S. and No. 4 worldwide for anthropology based on the number of publications in top-tier journals.

Unlike other schools that silo anthropology into its own department, the School of Human Evolution and Social Change is the department home to many of the university’s social scientists, global health experts and even faculty in applied math. It is also affiliated with more than ten research centers, including the Institute of Human Origins, the Center for Global Health, the Center for Evolution and Medicine and the Center for Social Dynamics and Complexity.

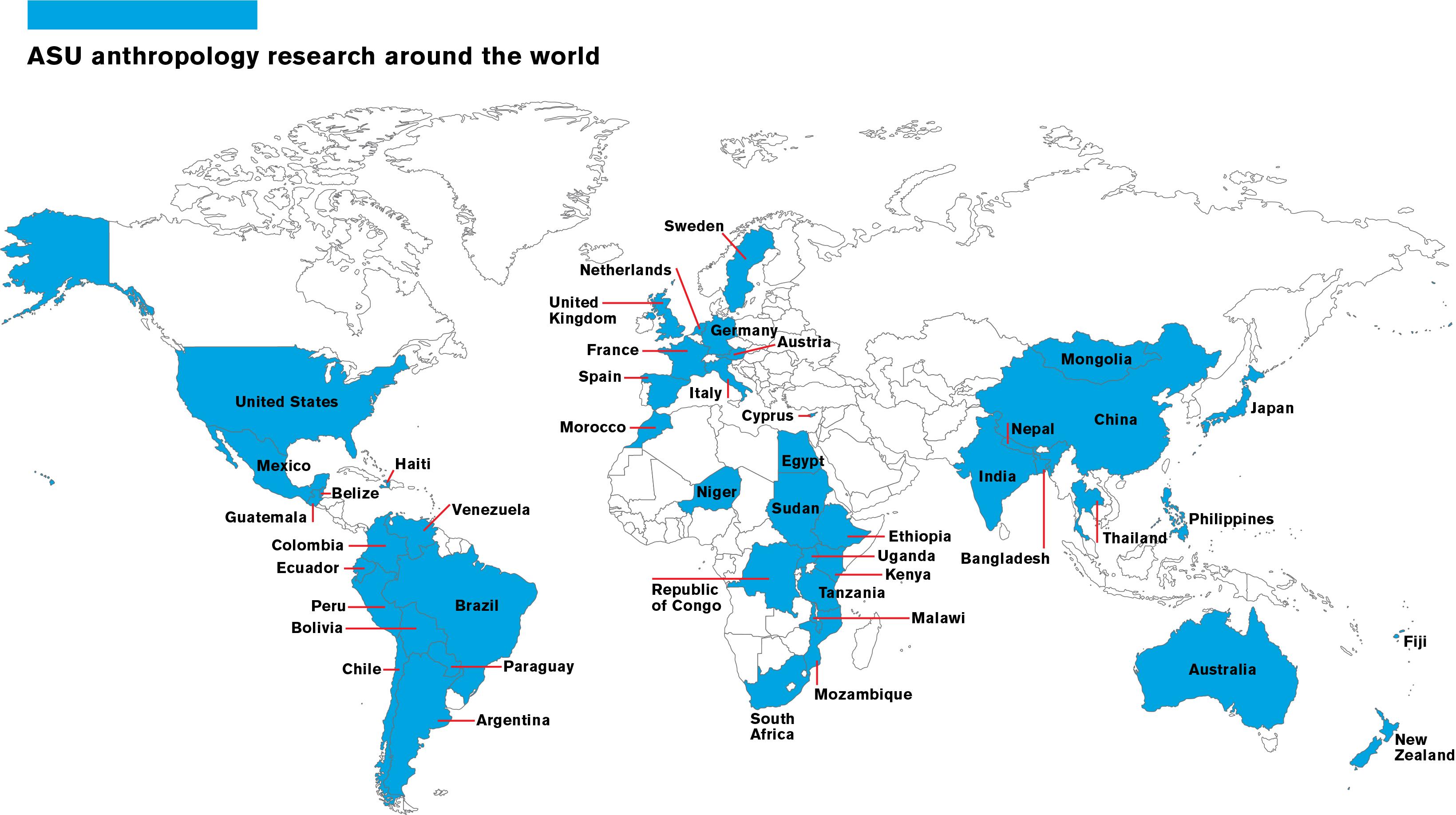

Reed said this exemplifies one of ASU’s strengths in anthropology: faculty are working around the globe and across disciplines.

This approach may explain why three of the seven ASU fellows elected to the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2017 were anthropologists. Alexandra Brewis Slade focuses on how health-related stigma, like being overweight, shapes the human experience. Michael Smith studies ancient central Mexico and the differences and similarities between urban areas in the past and present. Maria Cruz-Torres studies the social and cultural aspects of the human experience and in particular gender, globalization and the environment.

“What makes us innovative is that everybody has their own take on a piece of the field of anthropology. It's a global endeavor,” Reed said.

Over the past two decades, ASU anthropologists have conducted research in more than 40 countries.

Piecing together an ancient puzzle

Reed’s research focuses on how our ancient human relatives evolved and lived and how our human species, Homo sapiens, came to be. She is in good company at ASU. The university has a legacy of human origins discovery and scholarship, anchored by the Institute of Human Origins, which is recognized as the leading research center for the science of human origins.

The Institute of Human Origins (IHO) was originally founded in Berkeley, California by Donald Johanson, who uncovered the most famous skeleton known around the world: Lucy, an early ancestor to modern humans. In 1997, Johanson moved the institute to ASU. Its mission expanded to include training the next generation of human origins scientists.

Donald Johanson with the world-famous human ancestor skeleton that he discovered in Ethiopia in 1974. Lucy, of the pre-human species Australopithecus afarensis, is named in honor of the Beatles’ song "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds."

“Since IHO moved to ASU it has become the preeminent research organization devoted to the science of human origins — paleoanthropology. IHO’s growth would not have been possible without the outstanding commitment of a major research university, and a nationally ranked anthropology department. This partnership is unique and as ASU grows, IHO’s commitment and capability is expanding to embrace the seminal question of how we became human,” said Johanson, professor and Virginia M. Ullman Chair in Human Origins in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change.

The Institute of Human Origins has a long-term commitment to strategically important field sites and cutting-edge analysis. Discoveries at South African cave sites reveal how the earliest modern humans evolved before and after the great diaspora out of Africa. Photo credit: Donald Johanson

“Increasing public understanding of our origins is a central part of IHO’s mission,” said William Kimbel, current director of the institute. “IHO scientists not only produce cutting-edge research, but in the classroom, in the lab and at our far-flung field sites, we use our research to inspire the next generation of scientists.

Piecing together the fossil record of pre- and early humans can be like working on a puzzle — a really, really challenging puzzle of which someone has hidden or lost many of the pieces. This is why finding even a small piece of the puzzle can be a breakthrough discovery. Like uncovering a jawboneA missing fossil link: Prior to the jawbone discovery, scientists had evidence of the earliest human ancestors, like Australopithecus afarensis (Lucy), that dated to 3 million years and older, and of modern human fossils dated to 2.3 million years and younger. The hominid jawbone is dated to 2.8 million years ago and provides the first evidence of human ancestors between these two time periods. in the Ethiopian desert.

This is also why Reed and her colleagues often look beyond hominid — human and human relative — bone fossils. They also look for clues about the type of plants that grew and what the climate was like long ago. Using these approaches, they have been able to infer what some aspects of life might have been like for early humans and even their behavior.

The challenges of modern humans

Amber Wutich is trying to piece together a different kind of puzzle. She is a cultural anthropologist, professor and director of the Center for Global Health, studying how humans live today. Wutich wants to understand the human response to resource scarcity, like a lack of water. By collecting information about the communities and populations affected by resource scarcity, her team can share information with the communities they work in and with agencies in positions to assist and create policy.

Sometimes the answer might come from a distant place. Wutich worked with Brewis Slade to initiate a global study to understand how people think about and use water. The Global Ethnohydrology Study is taking place at four field sites around the globe: Bolivia, the U.S. (Phoenix), New Zealand and Fiji. Each location faces a different set of water challenges, such as contamination, diminishing water supply or inadequate infrastructure. Comparisons between the sites can illuminate possible solutions that are the best fit for a region.

As part of another international project, Wutich and her colleagues are innovating the very methods used to conduct anthropological research. Traditionally, to understand a present-day culture and its social norms, anthropologists spend months, even years, collecting information. This would include one-on-one interviews, reading archival material and observing behaviors. While these in-depth methods will always be valuable, Wutich says researchers also needed the ability to gather information more quickly.

The Global Impact Collaboratory addresses this need. Working at international field sites, Wutich and her colleagues have developed guidelines for rapid ethnographic assessments — information about people and their culture — that can be completed in a matter of weeks, not months. This is allowing anthropologists to collect accurate data more efficiently.

For example, Wutich was in Paraguay as part of a cross-cultural study about the stigma around obesity and what it’s like to live in a large body in different contexts around the world. Using the new approaches she helped to develop, Wutich was able to identify the people to interview, ask the right questions and get exactly the information she needed in a short time. She described the experience as being one of her favorite research experiences to date.

These techniques are particularly helpful for people working in development agencies like the U.S. Agency for International Development. ASU EdPlus, with support from the Institute for Social Science Research, is developing an eight-hour online workshop based on the work of the Global Impact Collaboratory. The workshop will allow anyone in the world to learn techniques of rapid assessment in a day. Incorporating these new methods and making them available to all is something Wutich sees as an example of ASU’s dedication to teaching, innovation and working at scale, part of what sets the university apart.

Although Wutich’s research is not focused on fossils, she sees enormous benefit to working alongside colleagues grappling with the unknowns regarding ancient humans. What distinguishes anthropologists, she says, is that they aren’t satisfied by answering questions only for a particular time and place. They want to understand the broader implications.

One degree, many opportunities

Just as anthropology faculty at ASU are researching the human experience beyond “bones and stones,” the opportunities for anthropology graduates are diverse.

A foundation for all degree programs in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change is learning respect for all cultures and understanding the great breadth that exists in the human experience, including lingering issues such as injustice and inequality.

Hands-on experience and involvement in research is also emphasized. Reed says this makes ASU anthropology graduates well-prepared for diverse career trajectories and sought after by employers. Some graduates land jobs in business, where they add value because of their training to understand and appreciate different perspectives and diversity.

Graduates can also go on to pursue medical degrees, some with a focus on helping marginalized populations such as refugees, children, ethnic minorities, and LGBT patients. Wutich observes that a common motivation across ASU anthropology graduates is an interest in making a difference in the world.

“I come to work every day with an incredible passion for our mission as a university. To know that not only are we having the opportunity to impact students’ lives in a positive way but that we are training and readying those students to go out into the world and impact dozens or hundreds or thousands of people makes this the greatest job in the world,” Wutich said.

In the age of selfies, questions of the self

Anthropology background or not, we humans have an inherent curiosity about ourselves. This is why we’re fascinated both by pictures of what our friends had for breakfast and by discoveries about our early human ancestors. We seem to have an insatiable curiosity to find out, “What is everyone up to?” — even millions of years ago.

“People want to know where we came from. They want to know how we became human. To understand that you have to piece together the past,” Reed said.

“Every day you get up and think, ‘What am I going to find today?’”

— Kaye Reed, director of ASU's School of Human Evolution and Social Change

Beyond our innate curiosity, studying early and modern humans can help us understand how we’ve faced challenges in the past, providing clues about how we might face them today. For example, Reed and her colleagues are working to understand how ancient humans might have coped with a changing climate, as these answers could inform how we adapt to climate change today.

Reed continues to work at the field site in Ethiopia, the same place where Seyoum found the hominid jawbone. Her team has identified a new section of the site to explore. She hopes to find another fossil of a distant relative, providing new clues from our past and further illuminating our future. Her excitement is palpable as she describes an upcoming trip.

“Every day you get up and think, ‘What am I going to find today?’”

Top image: designed by Claire Doddman

More Arts, humanities and education

Local traffic boxes get a colorful makeover

A team of Arizona State University students recently helped transform bland, beige traffic boxes in Chandler into colorful works of public art. “It’s amazing,” said ASU student Sarai…

2 ASU professors, alumnus named 2025 Guggenheim Fellows

Two Arizona State University professors and a university alumnus have been named 2025 Guggenheim Fellows.Regents Professor Sir Jonathan Bate, English Professor of Practice Larissa Fasthorse and…

No argument: ASU-led project improves high school students' writing skills

Students in the freshman English class at Phoenix Trevor G. Browne High School often pop the question to teacher Rocio Rivas.No, not that one.This one:“How is this going to help me?”When Rivas…