Shots fired in 1918 Arizona still resonate

Editor's note: This story is being highlighted in ASU Now's year in review. Read more top stories from 2018 here.

Four minutes.

Twenty-six bullets.

Four dead.

A manhunt spanning hundreds of miles.

One of the longest prison sentences in Arizona history.

And two old men, ghosts from the Old West, freed from prison by a crusading newspaper columnist, into a world of freeways, jetliners and space exploration.

This is the story of the Power brothers. One of the West’s most amazing tales, it’s mostly unknown except by Arizonans of a certain age. And it began with a bloody shootout at dawn a hundred years ago this Saturday.

A tragedy in the mountains

Before dawn on a bitterly cold morning on Feb. 10, 1918, a posse of four men sat on their mounts in a remote canyon in southern Arizona. They looked down at a small cabin. Smoke trickled from the chimney.

The posse — a county sheriff, two deputies and a U.S. marshal — were there to arrest the four men in the cabin below. Jeff Power, his sons Tom and John, and a hired hand named Tom Sisson lived there, working a mining claim. The brothers were wanted for draft dodging. Jeff Power and Sisson were wanted for perjury.

The posse dismounted, tied up their horses and removed their heavy clothing to be as quiet as possible. They crept down to the cabin and surrounded it, with the marshal, Frank Haynes, in the back. Sheriff Frank McBride and his deputies, Martin Kempton and Kane Wootan, waited in front.

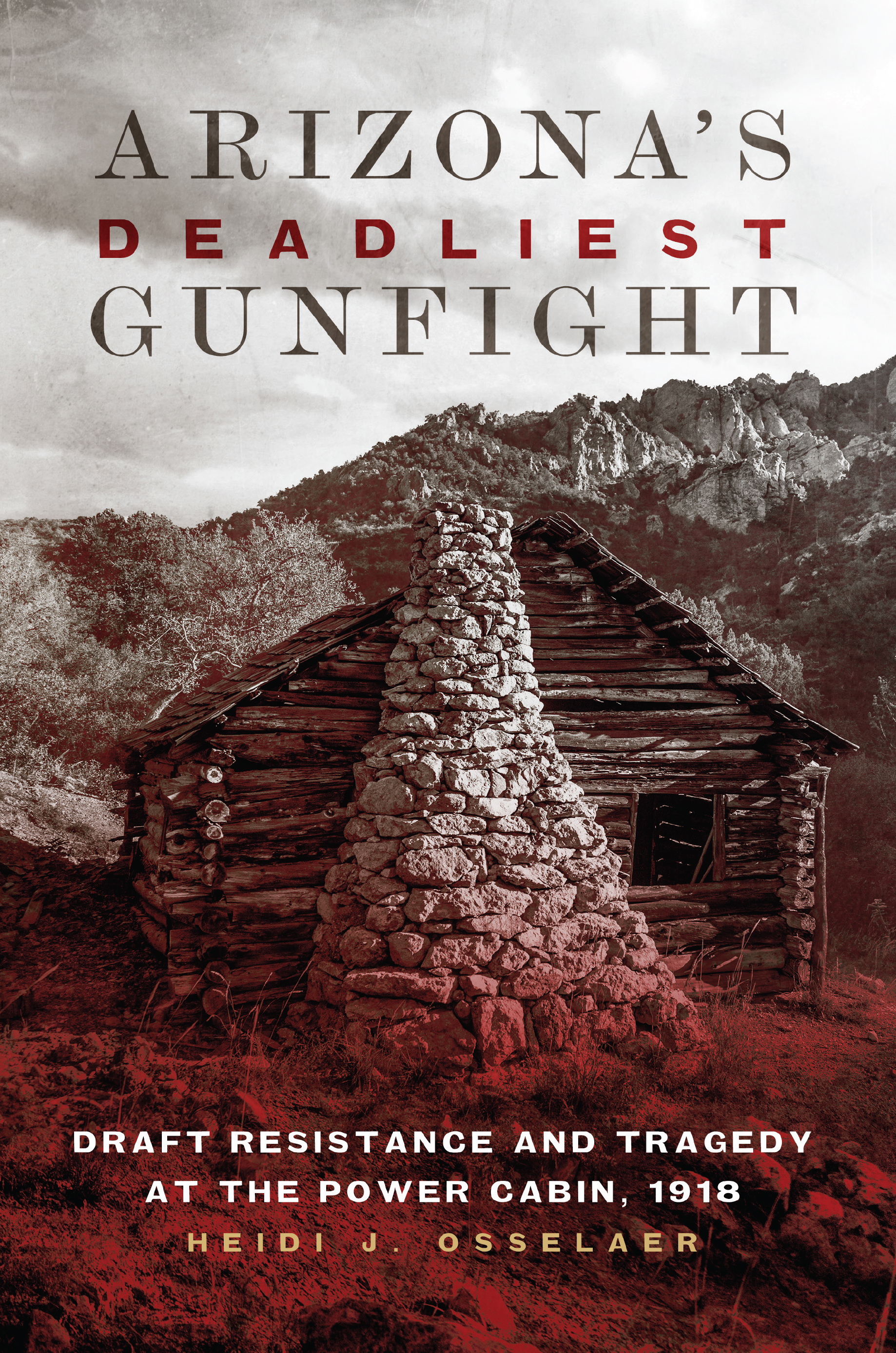

“I guess they had planned this out, but perhaps the plan wasn’t obviously as good as it could’ve been,” said Arizona State University historian Heidi Osselaer, who executive-produced a documentary about the story called “Power’s War.” She has also written a book, “Arizona’s Deadliest Gunfight: Draft Resistance and Tragedy at the Power Cabin, 1918,” which will be published in May by the University of Oklahoma Press.

The Power family had a young colt, which was belled so they could find it in the mornings. They heard the bell on the colt and thought a mountain lion was stalking it. Jeff Power went to the door in his long johns, carrying his rifle.

“He walked outside with his gun, which is what a mountain man would do,” Osselaer said. “In every place he had lived his whole life, he had had trouble with people trying to rustle cattle, trying to jump mining claims; he had had a lot of problems with that over the course of his lifetime.”

Someone yelled from the dark, “Throw up your hands!”

He put his rifle between his knees and put up his hands. A bullet slammed into his chest.

Later on, both sides claimed the first shots came from the other side.

“We just don’t know,” Osselaer said. “I think, probably, we’ll never know that. I think whenever you get armed men, facing each other, in the dark, unexpectedly, bad things can happen. To me, it’s more important to know why was the posse up there to begin with? Usually, you won’t get a posse unless it’s some violent crimes and really dangerous people. They were up there with misdemeanor charges of draft evasion and perjury. That’s it.”

There was a lull of about a minute after the first shot.

Then all hell erupted.

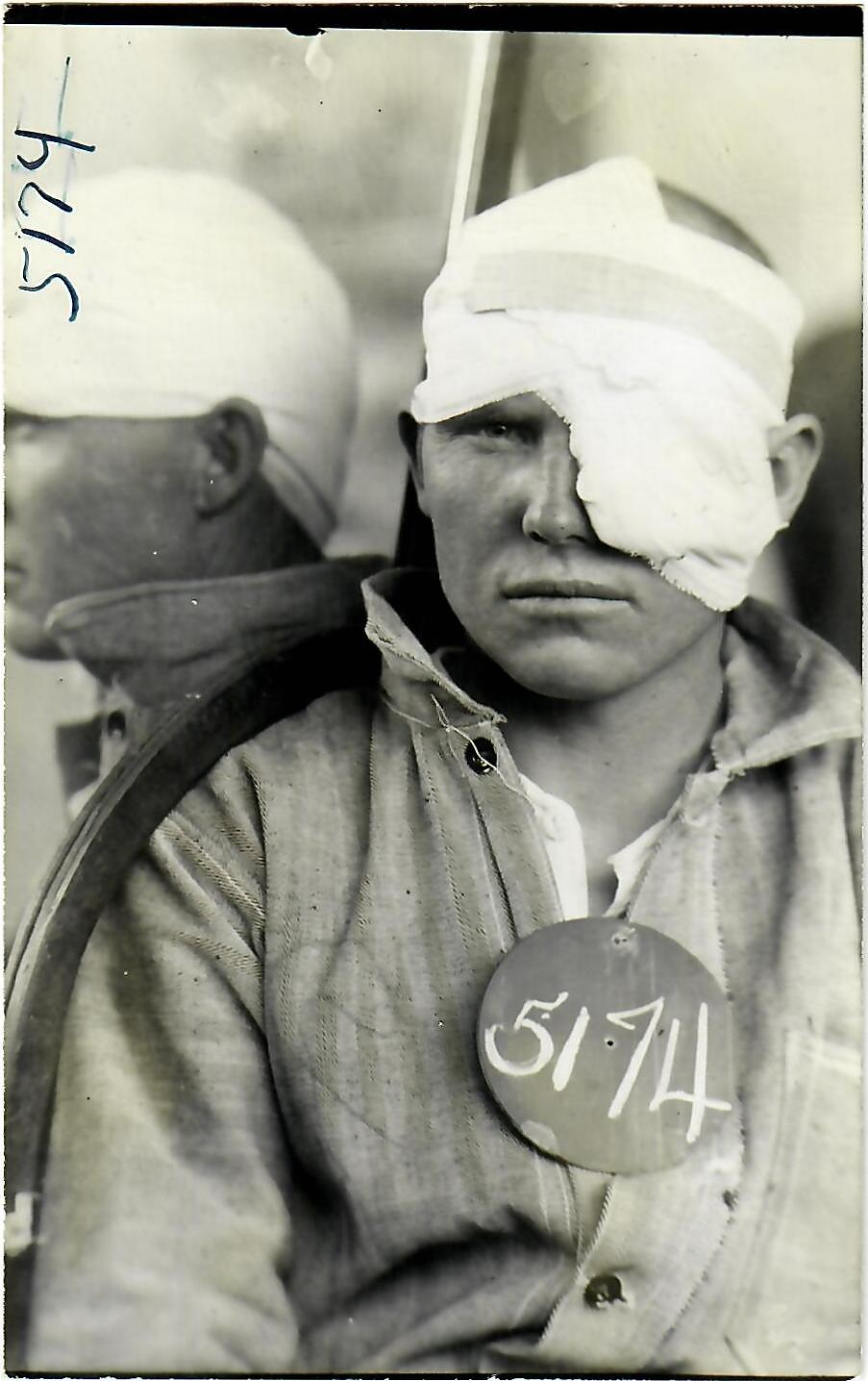

Bullets shattered the cabin windows. John Power’s left eye was riddled with wood splinters, and his nose was creased by a round. His older brother Tom’s left eye was filled with glass shards. Three minutes and about 25 shots later, the gun battle was over.

“Some of us who have been in firefights know that there’s nothing in the world more unsettling to the human memory than that kind of desperate mortal combat,” said Don Dedera, an ASU alumnus (Class of 1951) and veteran journalist who broke the Power brothers’ story in 1958.

Outside, Sheriff McBride lay dead with four bullet wounds. Both deputies were killed, one shot in the back and the other in the stomach. Jeff Power was mortally wounded.

The marshal, who had been behind the cabin when the shooting started, fled. He bolted for town so quickly he rode his horse to death.

A death and a dodge

The story sheds light on a unique period. Arizona is — and always will be — the Wild West of shootouts and feuds and bad men. But the Power brothers story isn’t just another outlaw story, Osselaer said.

“These weren’t a bunch of hotheads; these weren’t a bunch of outlaws,” she said. “It was brought about, in my mind, solely because of World War I. Men who didn’t want to fight really saw this as an intrusion on their ability to earn a living, to take care of their families, that they didn’t want to go fighting in Europe for some old-fashioned aristocracies. This was a young country — we were a democracy, and a lot of people sympathized with men who didn’t want to go fighting overseas.”

Video by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

World War I bitterly divided the country.

After an early isolationist stance, the U.S. entered World War I in 1917, and an unrelenting stream of propaganda swept across the country: sermons, rallies, lectures, newspaper articles, parades, posters. Rural people weren’t buying it.

“I think some people in the countryside just didn’t realize how dangerous it was to protest,” Osselaer said. “You could be arrested for something as stupid as saying, ‘I believe this war is nonsense, so we shouldn’t get involved.’

“Anybody who wanted to protest or had arguments against the war, didn’t want to participate, didn’t want to join the Red Cross, didn’t want to contribute to buying war bonds … those people were really treated as almost criminals, and they were very much told that they were disrespectful, unpatriotic,” she said. “They were outcasts in society.”

And then two things happened around the end of 1917 that would set the stage for the shootout. First, the Supreme Court heard arguments about the Selective Service Act — the draft law — and voted to uphold it the first week of January 1918.

The second event was the death of Ola May Power, Jeff Power’s youngest daughter, under mysterious circumstances at their home in Rattlesnake Canyon. Her mother died when she was a young girl, and her grandmother died in 1915; an unchaperoned young woman of 23 living alone with her father, her two brothers and a hired hand was not deemed proper. Scandalous rumors circulated in the Gila Valley that she had died at the hands of her own family. There were whispers of a botched abortion.

“All of these horrible things were being said about her, even printed in the newspapers,” Osselaer said.

An autopsy was performed, and it was inconclusive.

Enter Graham County Sheriff Frank McBride.

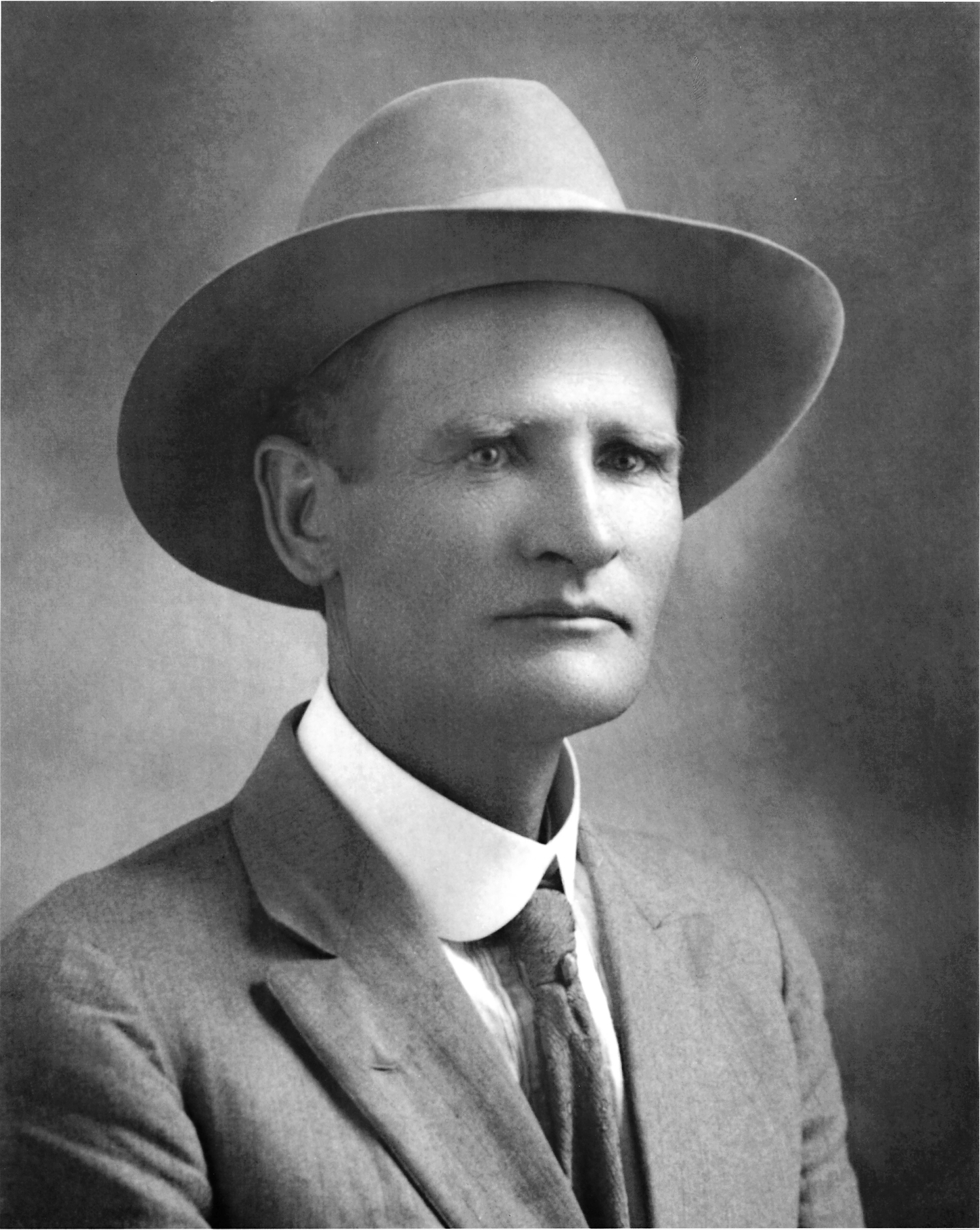

Sheriff Frank McBride of Graham County, 1916. Photo courtesy of the McBride family

A man of the law

McBride was a city dweller. He lived in the Gila Valley, he was a Mormon and he upheld the law in the strictest terms. He sometimes came into disagreements with the folks who lived in the more rural parts of his jurisdiction, people like the Power family.

The Powers came from Texas, settled in New Mexico for a while and then Arizona; they were rural ranchers, and they were very different from farming families of the Gila Valley. The Powers lived by their wits; they lived off the land, hunted their own meat and rarely went into town for supplies.

“(Graham) would ride up there and say, ‘You guys are all poaching, you’re hunting out of season,’ when that was sometimes the only meat that these people had to put on their tables,” Osselaer said. “This was the progressive era when the state Legislature was passing a lot of laws: hunting laws, prohibition laws, things like that that didn’t always sit well with the folks in the mountains.”

When McBride was elected sheriff in 1916, he received almost no votes from rural precincts. His support came from Mormon communities down in the valley. They expected him to uphold those progressive laws and, when the war came, to make sure that people were registered for the draft.

At the inquest into Ola May Power’s death, her father testified under oath that her final words were, ‘Poison, poison, poison,’ and that he didn’t know what happened. Sisson also testified he had no idea what happened.

Those responses did not sit well with McBride.

After the inquest, Jeff Power, his two sons and his hand mounted up and returned to the mountains, happy to leave society at large — and the draft law — behind.

The law that Tom and John Power were breaking, however, was a misdemeanor, not a felony. It wasn’t a big crime. The maximum sentence for failing to register for the draft was a year in prison. And the Power brothers were solidly on the federal government’s least-wanted list. More than 3 million men had failed to register. The government didn’t have the money to go after them all.

But McBride had been diligent in rounding up slackers, as draft dodgers were called, and it irked him that the Power family was holed up in the mountains out of reach.

“You can see in the letters that he writes to the U.S. marshal, that he writes to the Department of Justice — he’s agitated, the sheriff is, by the fact that there are so many men that aren’t registered for the draft,” Osselaer said.

“I looked at the federal records to look at why this posse was formed,” she said. “One thing is very clear: the federal government could (not) care less about the Power family. This was really driven by local politics in Graham County in Gila Valley.”

Even though the provost marshal made a ruling that local sheriffs could go after draft evaders, it was expensive: three to four men gone for days on end, being paid and provided with food and lodging. A lot of sheriffs just threw their hands up and forgot about it.

Not McBride. His letters show he wanted to do it, but he didn’t have the budget, and the federal government wouldn’t send him anything to help. But now, with the death of Ola May Power, he had a reason to arrest them.

McBride obtained warrants from the federal government for draft evasion for the two boys and perjury warrants from the state, issued in Graham County, for Jeff Power and Sisson. He believed they hadn’t been telling the truth about Ola May. He told people he wanted to investigate, not to mention bring the slackers to justice.

“This isn’t a Mormon vs. non-Mormon story, but it’s maybe more a small-town folks vs. the country folks who viewed the coming war with different lenses,” Osselaer said. “I would say without a doubt the Powers knew they were wanted for draft evasion, but I don’t think they quite understood how quickly the public mood had changed.”

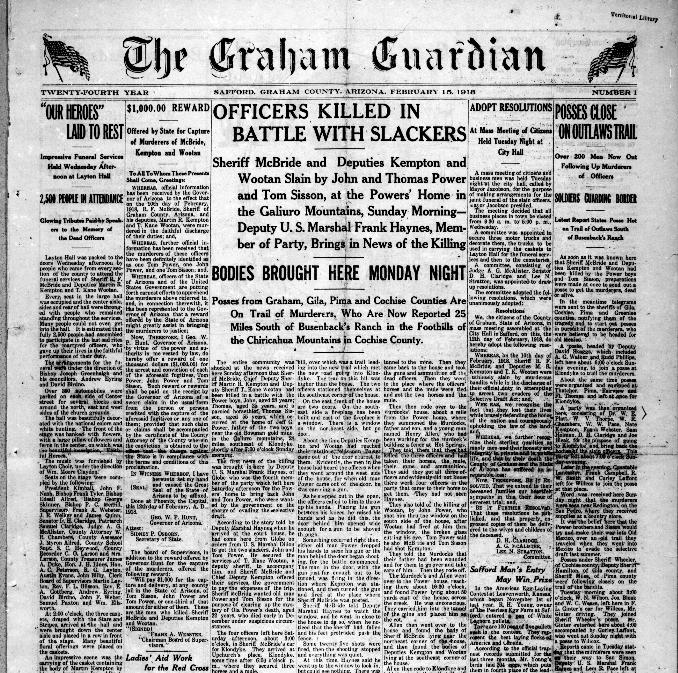

A copy of The Graham Guardian, of Safford, from Feb. 15, 1918, announces the Feb. 10 gun battle that killed four people including three lawmen. Image courtesy Arizona State University

An epic chase

McBride and his posse left on a Saturday out of Safford. It was the beginning of one of the earliest snowstorms of the season. They drove about three hours on dirt roads up to Klondyke. They had supper and left late in the evening on horseback and mule, heading into Rattlesnake Canyon to look for the Powers.

They found them shortly before dawn.

After the shooting ended, the brothers and Sisson leaned over Jeff Power and knew the wound was fatal. They examined the bodies in front of the cabin and discovered who they had killed.

“We had no idea why they had come after us,” Tom said later in his autobiography. “We knew, because they were officers, that it was not safe to stay there.”

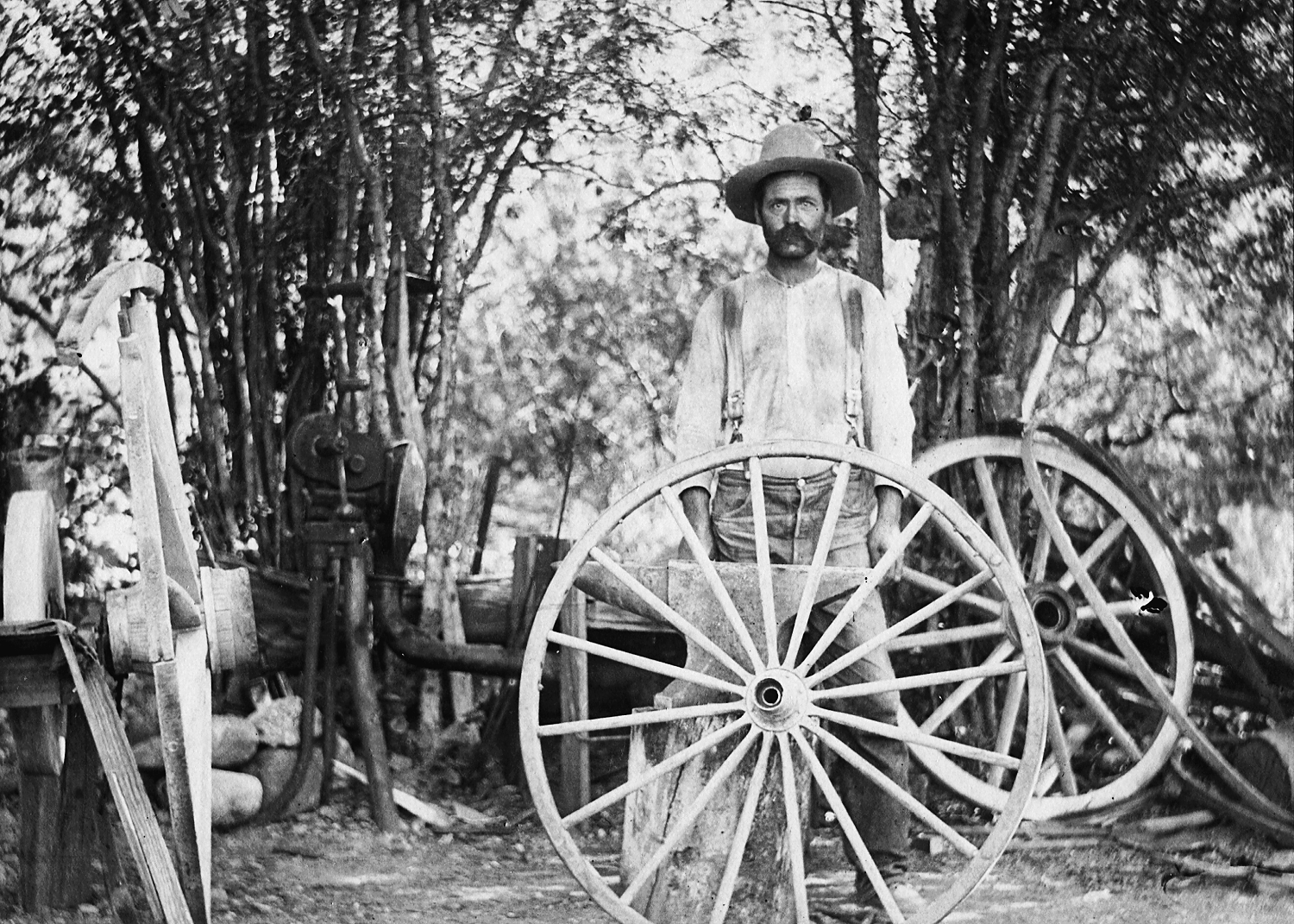

They decided to run for Mexico, reasoning they would be killed when the news got out. Sisson, an ex-U.S. Cavalry trooper who knew southeastern Arizona well, volunteered to come with them. (Sisson, in bed during the shootout, never fired a shot.) They took the posse’s two horses and mule that had been left tied near the cabin and rode a few miles north to the home of a neighbor named Jay Murdock.

Tom Sisson was a private in the U.S. Cavalry before he settled in Klondyke, where he homesteaded, worked as a blacksmith and befriended the Power family. Photo courtesy of Howard Morgan

They told Murdock they had killed three lawmen. They asked him to go take care of their father and rode off.

“Both of them were wounded, terribly so in the eyes,” Dedera said. “Can you imagine a wood splinter in your eye and in the other one a bunch of glass, and having to live with that on the trail?”

Down in the valley, the shootout created three widows and left 19 children without fathers. The tightly knit Mormon community was transfixed by the horror of what happened to their sheriff and deputies, Dedera said.

Thousands of men hunted them, on horseback, in trucks and cars, and with two military planes. Thomas Cobb, author of a novel about the Power brothers, noted that the gunfight was a 19th-century event while the manhunt happened in the 20th century.

The Powers and Sisson made their way south from the Galiuro Mountains, spotting truckloads of men with rifle barrels sticking out, hunting them. A few times they were so close to posse members they could have reached out and touched them. They stopped at a house and bought some food. The residents reported them after they left, and the pursuit heated up. While they saw posses several times, they avoided detection for weeks.

They came across cowboys who had heard their story, young men like themselves who sympathized with them and supplied them with food and fresh mounts. Sisson, with his military background, did what he could for their wounds.

They passed through the San Pedro Valley and crossed into the Chiricahua Mountains. At times it snowed heavily and they built lean-tos out of logs and bear grass. They starved for days, then shot and butchered calves and cattle.

They came out of the mountains and crossed into New Mexico, where the local sheriff had promised in the press that he would kill them if he had the chance. They bought food from a woman whose husband was out hunting them. The couple then alerted the authorities, who literally called in the cavalry from El Paso.

The brothers and Sisson made it into Mexico, but cavalry patrols tore down the border fence in pursuit.

In the end, they were not captured. They surrendered to Lt. Wolcott P. Hayes.

Hayes took only six of his soldiers with him across the border. The civilian lawmen stayed behind, concerned about jurisdiction.

The cavalry patrol went across the border and headed about five or six miles south. Hayes had two men with him.

“I turned around, and I was suddenly looking down three of the biggest gun barrels I had ever seen,” Hayes said later.

He jumped off his horse, but they didn’t shoot.

“We’d never kill a soldier boy, but if you’d have been those sheriffs that are hunting us, we would have killed you,” they told him.

They were filthy, starving and shoeless, with no water. John’s eye socket crawled with maggots.

“They just couldn’t go any further,” Dedera said.

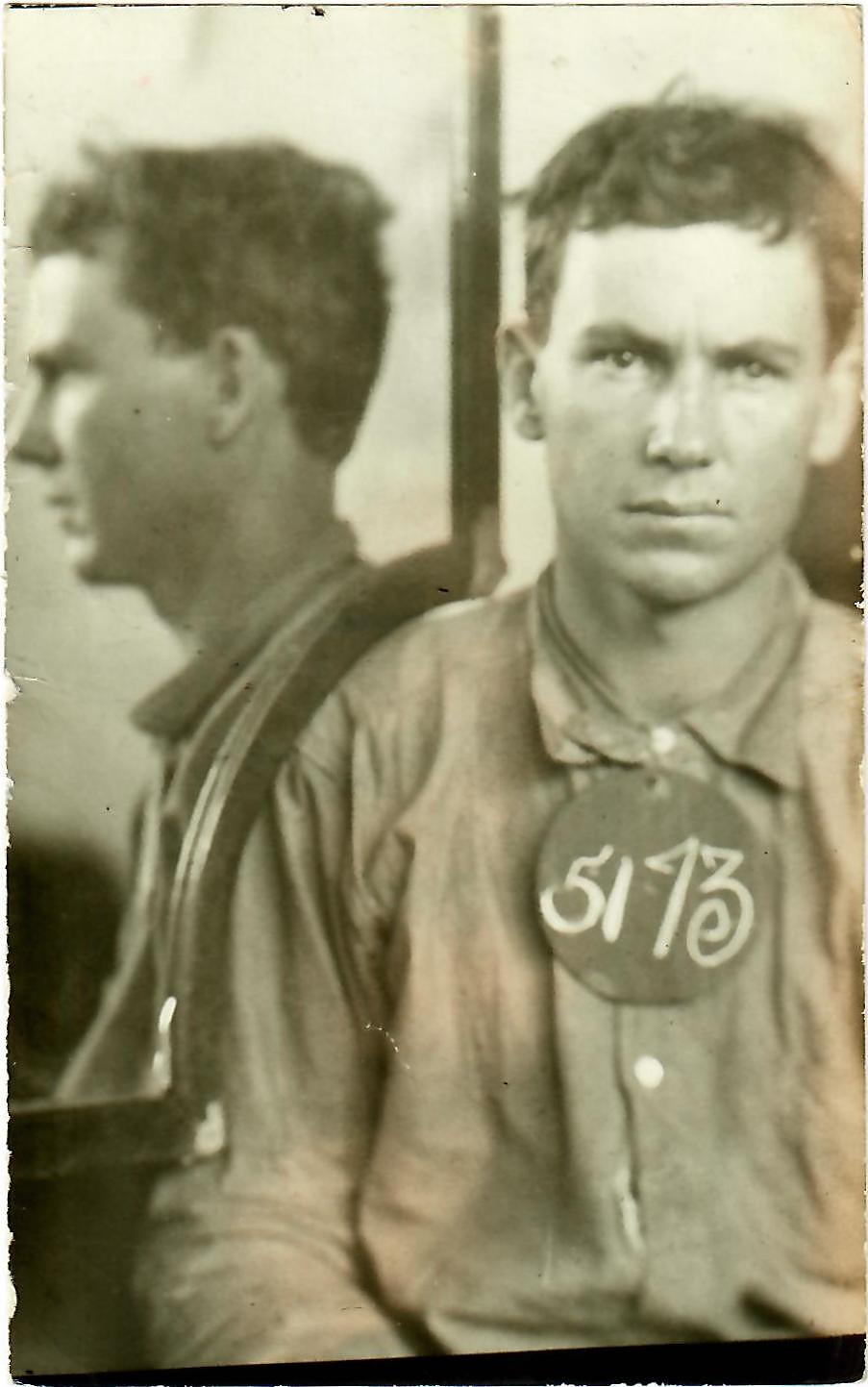

Thomas Jefferson Power Jr.'s booking photo from 1918 Florence prison pictures. Photo courtesy of the Pinal County Historical Society Museum

A circus of a trial

The three men were handed over to civilian lawmen and transported back to Safford.

“What happened after that would send today’s ACLU into permanent orbit,” Dedera said. The new sheriff of Graham County operated a kind of carnival sideshow: For a dime or quarter, people could pass through to gawk at the prisoners.

Furious mobs also surrounded the jail.

“There was just bloodthirst,” Osselaer said. “People wanted these guys hung, and they had to go under close guard all the time.”

The Powers’ older brother, who lived in New Mexico, sent defense attorney James Fielder, who once had defended their father.

Both Fielder and the county district attorney took one look at the situation and had the prisoners moved north to Clifton.

John Grant Power's booking photo from 1918 Florence prison pictures. Photo courtesy of the Pinal County Historical Society Museum

The three of them were tried together; the trial lasted only five days.

“The whole thing was a circus,” Osselaer said. Evidence that the first shot may have come from the deputies was not admitted into the trial.

“So I think that was key to the trial; they couldn’t claim self-defense,” Osselaer said.

All the official documents related to the trial vanished. Dedera couldn’t find anything in the late 1950s, and Osselaer came up with little after scouring county, state and federal archives.

The court transcripts are missing, and newspaper coverage is of little help: It was nearly impossible to report on a trial about draft dodgers when anti-war talk was censored.

“So you just have huge blocks of testimony that would normally be copied verbatim in the newspapers,” Osselaer said. “It’s summarized in one line: ‘Many witnesses gave testimony that there was premeditated murder.’ And that’s it. It was all blocked by the censorship.”

The three men were sentenced to life in prison. Arizona had abolished the death penalty the year before.

“Many of the people in the upper Gila Valley felt they had been deprived of the one thing that might have evened the score — the death penalty,” Dedera said. “(But) by God, if the only thing left was life in prison, they were going to have to die in prison.”

A life lived in prison

For the most part, the three men were model prisoners.

They were on the honor system, let out to work: milking cows, picking fields or building roads. The brothers earned money by making spurs and tack, which were sold to the public in the prison store. They were paid $15 for every $100 sold.

In the early 1920s, Tom escaped briefly with another convict.

“He had been repeatedly refused even parole here,” Osselaer said. “The wardens will tell you this and said this repeatedly about these guys, ‘When you give somebody no hope, what are they going to do?’ They become a flight risk.”

The brothers escaped together to Mexico in the 1930s, evading capture for three months. It was during the Great Depression and state budgets were cut to the bone. The warden had to let guards go. There wasn’t money to buy gas for the prison’s cars, so if men escaped, there was no way to go after them.

While they were at large, there was concern in the Gila Valley that the brothers would come after the widows of Kempton and McBride, but officials weren’t worried. The prison warden said, ‘You know these guys are harmless. They’re riddled with arthritis from hard, physical labor their whole lives. I’m not worried about them hurting anyone.”

Their first probation hearing came in 1952. Hundreds of people showed up to protest any kind of leniency. Their case had been reviewed many times over the years, but never with a public hearing.

“In all that time they had one superficial parole hearing,” Dedera said. “Parole denied. Bang! One shot at freedom and it was automatic.”

The Powers didn’t break any laws while on the outside. They did a stretch in solitary after the Mexico excursion, but were back on the honor system in a few months.

Sisson never made an escape attempt and never caused a moment’s grief in prison. He died in 1957 in his late 80s.

The Powers’ good behavior in prison won the guards and officials over. By the late 1950s, they weren’t even living on prison grounds. They were living in a line shack they maintained outside the walls, tending to the horses, walking around freely.

By this time, the brothers were in their mid- to late-60s, the oldest inmates at Florence and in and out of the prison hospital all the time. Over the years, prison guards and wardens submitted applications to have their case reviewed. Every time, the families and descendants of the three victims got petitions together and called the governor.

“I’m not saying the Powers shouldn’t spend some time in jail, maybe on manslaughter or second degree, and certainly they evaded the draft and they were stupid about it,” Osselaer said. “But at the same time, should they have spent their life in prison?”

A journalist takes up for the Powers

It was 1958. Dedera, then 29, was the star columnist for The Arizona Republic, cranking out 300 columns a year. He had the most widely recognized name in the state. (“It was a pain in the (rear). ... That’s what celebrity is like.”)

One day he went down to Florence to interview a convict. The warden sat through the interview, and the convict was led back to his cell. Dedera was collecting his notes when the warden said, “There’s a better story down here in the Power brothers.”

“Who are they?” Dedera asked.

“I can have ’em up here in 20 minutes,” the warden said. “You find out.”

Mostly out of courtesy, Dedera waited. Two old men were led into the room.

“I never heard (John) say a word in all the time I knew him thereafter, and certainly not that day,” Dedera said. “He just sat there under his pith helmet. His brother wore a cowboy hat, and he was the loquacious one.”

Tom had taught himself how to read and write in prison, and his message to Dedera was simple.

“He was like that little doll that we gave our daughters — you know, with the string in the back?” Dedera said. “He was like you’d pull the string in the back and he’d say, ‘My father was standing in the doorway when the sheriff shot him down.’”

The brothers pushed an envelope across the table with $1,000 in cash in it. It was a retainer, Tom explained. Dedera told them he was a journalist, not a lawyer.

“Tom then went ahead and spilled out this story.”

He talked about the marshal behind the cabin. Why they were there. The difficulty of living in a remote wilderness.

In Arizona at that time, murder one — practically speaking — meant seven to 11 years in prison. If you got life and behaved yourself, the parole board released you in that time frame.

“These guys were in prison for 10 years before I was born,” Dedera said. “They served another decade before I ever set foot in Arizona. We’re talking 20 years. They served another decade before I could get through school and my service and get through (Arizona State College) and get a job on the paper. Thirty years! They served another decade before I’m sitting across the table from them at Florence. That’s 40 years!

“The child reporter in me said the story is that these guys had not been treated fairly,” Dedera said. “That’s the thread of my series of articles that came forth after that.”

Having covered crime for five years, Dedera had seen his share of prisoners proclaiming their innocence. And he knew he couldn’t retry the case, not with the missing records and bowdlerized testimony.

So he decided to focus not on the Powers’ guilt or innocence in the shootout, but the unfairness of what happened after.

“It just seemed to be basically wrong that two men caught up in a wrongful situation when they were young would spend four times as much time (in prison),” he said.

Dedera wrote about 12 to 14 columns about the brothers. Fury erupted all over the state, and angry letters poured in. He began to wonder if he was going to get fired.

One morning, the secretary of the publisher of The Arizona Republic appeared at Dedera’s desk with a stationery tray holding about 200 letters.

“Mr. (Eugene) Pulliam asks if you would please answer these letters on his behalf,” she said.

Other than that, Dedera never heard a word from his publisher.

A call for forgiveness

A second parole hearing, open to the public, was scheduled in April 1960.

“I do not believe that anything in my life was ever more theatrically dramatic than the hour it took to process the second parole hearing,” Dedera said.

There were about 200 people there.

“I could feel the hot hatred bearing down on the back of my neck,” he said. “I’m the kid journalist that’s brought all this to pass.”

Three Mormon bishops stood up and spoke in favor of clemency. It was time for a resolution. It was time for the brothers to be paroled, they said.

Then, a Mormon elder in his 70s, Lorenzo Wright, the president of the Mesa stake and founder of a chain of East Valley grocery stores, took the stage.

“What a speaker! He doesn’t stand up in front and make a speech,” Dedera said. “He’s up and down the aisle like a lion of Judah! Wagging his finger at his beloved flock. A man of great respect, of a terrifically important religion. And he yells at them!

“He’s thundering at these people who have come for retribution and continued punishment, and he reminds them that all their books of guidance, from the Old Testament to the Book of Mormon, preach that there comes a time for resolution of hard feelings.”

Wright walked up and down the aisles, bellowing, “I want to hear that you are ready to forgive these men!”

Dedera recalls hearing a roar like you’d hear at a football game: “Yes! We forgive them!”

There was never a doubt to the parole board what to do, Dedera said. The next day they voted for commutation.

A week later, the Power brothers were released from the prison in Florence. Dedera waited at the iron gates.

John clutched a paper bag, which Tom handed to Dedera. Inside were a beautiful pair of handmade spurs inlaid with silver.

“We made parade spurs for you because we know you’re a dude,” Tom told him.

Don Dedera (second from left) talks with Tom and John Powers (right) on parole day (the man on the left is unidentified). Photo courtesy of the Power Brothers Notebook housed at ASU's Special Collections

A life and legacy on the outside

The brothers walked out of prison and into the future.

Other than crafting tack and managing livestock, the brothers had no skills to prepare them for modern life. They knew how to hunt, trap, blacksmith, pan for gold and wrangle livestock.

“Not what you would call a high-growth industry in the America they were freed into,” Dedera said.

A group of people, including Dedera, looked after the brothers, helping them find work and adjust to freedom.

Their first job out of prison was working at a children’s summer camp near Prescott, caring for the goats and ponies. Some of Arizona’s wealthiest families sent their children to the camp, where the brothers assisted with recreation. Later when Tom was a wrangler in Apache Junction, he taught Dedera’s 4-year-old daughter to ride.

There was some trepidation, Dedera said.

“One of my buddies said, ‘You entrust your daughter into the care of a murderer?’ I said, ‘He’s the kindest grandfather figure you can imagine.’”

Tom became fascinated with the space program and read all he could about it. He was also intrigued with Disneyland. Supporters arranged a visit to the park for him.

John moved to Silver City, New Mexico, for a period, where he built a line shack similar to the cabin in Kielberg Canyon. He traveled to Arizona from time to time to visit his brother and push for a full pardon. Eventually he returned to Graham County, where he lived in a trailer near the general store in Klondyke and worked a mining claim up in the mountains.

In 1970, they were pardoned by the governor of Arizona. The first thing they did was register to vote.

Dedera and Tom remained good friends, corresponding frequently until Tom’s death in 1970, shortly after the pardon. He was 77.

John died in 1976. He was 85.

Dedera went on to successfully cover Europe, the Soviet Union and the Vietnam War. In 1985 he became a charter inductee into the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism Hall of Fame at ASU. He went to work as editor-in-chief of Arizona Highways magazine, then continued a prolific writing career including 23 books and national awards. Dedera was recognized in 2007 as part of the Arizona Culturekeepers program for his dedication to Arizona's history.

In the Gila Valley, the shootout remains infamous, but it invokes less passion and fury than it once did.

“I can tell the latest generation is a little bit more ambivalent and not so certain it happened the way Grandpappy said,” Osselaer said.

Some Powers admit Tom and John were wrong for evading the draft, Osselaer said, while some on the lawmen side wonder why the posse went up there at all.

“I think that one of the most remarkable things is with time, you pull away and reevaluate,” she said. “(A) tragedy of this scope did not happen without there being real big mistakes on both sides.”

A memorial depicting the historical event with fairness and respect to both sides is planned for the town of Klondyke. Parties interested in donating may contact Lori Sollers, PO Box 167, Central, AZ 85531. Checks made payable to: Klondyke Senior Scholarship.

Top image: The Powers brothers leaving Arizona State Prison, Florence, in April 1960, after a parole board voted to commute their sentence. They were serving a life sentence for the murders of a sheriff and two deputies in 1918. Ten years after their release, Gov. Jack Williams pardoned them. Image from the Arizona Daily Star