Why should we go to space?

To learn more about the universe and our place in it? To extract resources and conduct commerce? To demonstrate national primacy and technological prowess? To live and thrive in radically different kinds of human communities?

These forking paths are at the heart of "Visions, Ventures, Escape Velocities: A Collection of Space Futures," a new collection of stories and essays about the near future of space exploration from Arizona State University’s Center for Science and the Imagination. The collection, which was supported by a grant from NASA, envisions space futures shaped by partnerships between public and private institutions, as well as new constellations of citizens, consumers and investors. These visions of the future were developed by collaborative teams of science fiction authors and experts in fields ranging from history and economics to astronomy, physics, engineering and even botany.

The collection of space stories is available for free download.

"Visions, Ventures, Escape Velocities" takes readers on gripping, occasionally mind-bending journeys to low-Earth orbit, Mars, far-flung asteroids and uncharted exoplanets. We caught up with one of the book’s editors — Ed Finn, director of the Center for Science and the Imagination and an assistant professor in the School of Arts, Media and Engineering and the Department of English — to discuss our changing consciousness about space, the nature of our motivations for going there, the evolving economics of space expeditions and Elon Musk’s Martian retirement plans.

Question: What were your motivations for putting together this project? What are you hoping that these new stories and essays will accomplish?

Answer: The stories that we tell about space are changing. We have moved from a series of totally novel technical challenges, like building rockets that can carry payloads to orbit and keeping humans alive in space, to a set of much more familiar challenges. The big barriers to our future in space are now social, legal, and economic — who’s going to pay for this stuff, how will it be insured, and why are we doing it? The essays in this collection tackle those questions: the intersection of space science, policy, commerce and society writ large.

We hope these stories can illuminate the future with a set of technically grounded science fiction stories that also draw inspiration from the past. Put aside the rockets and habitats and you see that humans have been solving similar challenges for hundreds, if not thousands, of years, from funding scientific expeditions to grappling with the ethics and politics of building new communities. To make the next steps in space exploration, we need to address these “why” questions, and we hope this collection offers some possible answers in its exciting, technically detailed space futures.

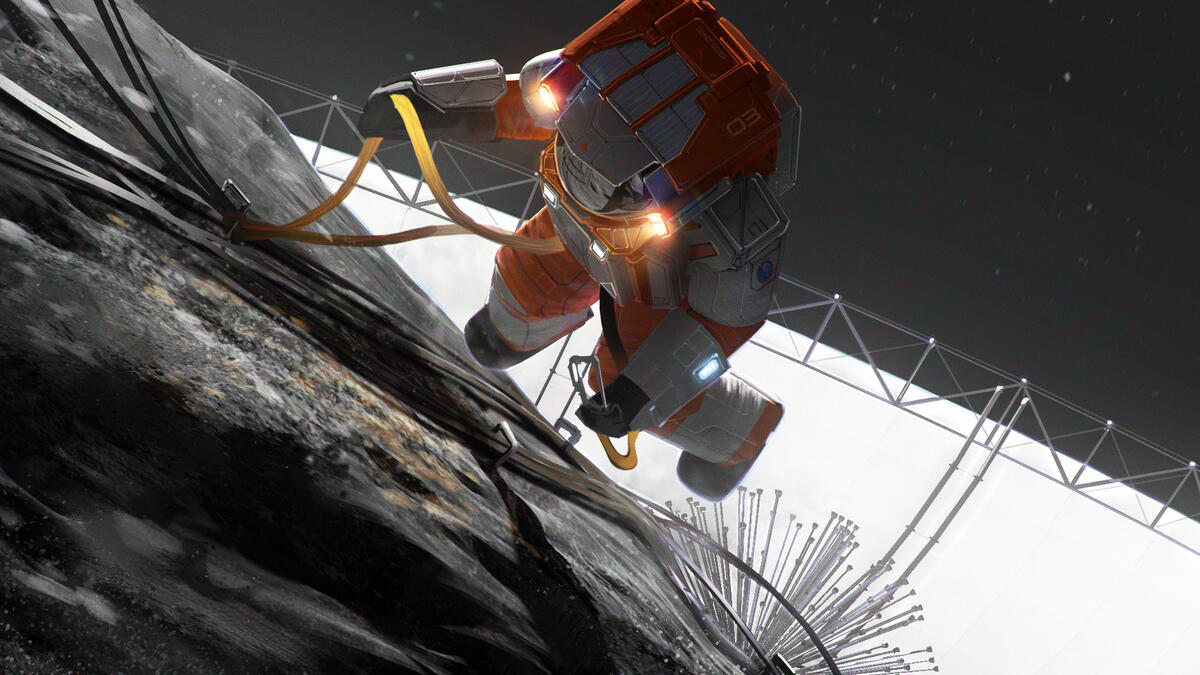

One of the book's illustrations by Maciej Rebisz.

Q: Asteroid mining has been a big part of most recent conversations about building a functioning economy in space. Do you think that’s the most promising direction?

A: The writers in this collection explored a whole range of possibilities, from nanobots breaking down asteroids to tourism in low-Earth orbit. Asteroid mining is certainly one major focus of space industry attention right now, and it makes sense that long-range expansion into space will depend on “in situ” resources, including the water and minerals on asteroids that can be converted into fuel and equipment.

But the asteroids are far away, and in the short term, we’ll be relying on established technologies and stuff we lug up the gravity well from Earth, so it’s good to speculate about other economic models. In his story, Karl Schroeder imagines that the development of human settlements on Mars will happen largely via robots controlled in virtual reality, and that the economics of space exploration will take a surprising, decentralized turn. Vandana Singh imagines a mission to an exoplanet funded through crowdsourcing. And two of our writers, Steven Barnes and Carter Scholz, think it will be the rich who get there first, creating businesses in Earth orbit that are really just extensions of the Earth economy.

Q: During the Cold War, the U.S. invested in space as part of a competition for national power and technological preeminence. What is driving our efforts in space today?

A: In a lot of ways this is the central question of an increasingly commercial sector. When we launched the Apollo program in the 1960s, it was a heady mix of hope and fear. Optimism and national pride on the one hand, as the U.S. came into its own as a global superpower after World War II. But also anxiety about military rockets, nuclear weapons and losing the technology race to the Soviet Union. Getting the first man on the moon was a race not just for prestige but to master this new arena of technology, making space another battleground in the Cold War.

Of course, companies aren’t in it to plant flags, and I think there are a number of groups hunting for the right business model. Today we are at one of those inflection points where something that used to be very hard is going to become significantly cheaper and easier. The details of how that shakes out will play a major role in determining what the new space economy looks like, as well as the new symbolic economy around why we are investing in space exploration, and what it means for people back on Earth.

Q: Elon Musk has famously proclaimed that he’d like to retire on Mars. Why is that such a provocative statement? After all, he’s not really talking about mind-blowing scientific discoveries or whiz-bang new technologies.

One of the book's illustrations by Maciej Rebisz.

A: What I really like about Musk’s retirement plans is that it’s not just a technical challenge, but a social and economic one. Sure, we’ll need to build some bigger rockets and solve some new problems, but retiring on Mars means much more than setting foot on Mars, or simply surviving there. It means creating a way of life, establishing a home, maybe planting a garden … dwelling there in a meaningful way. That is really cool because (pulling it off) will require answering all kinds of cultural and social questions about who goes to space and why most people aren’t even thinking about that right now. Several of the essays in this collection really delve into these economic and social consequences of building human communities in space.

Q: What works of science fiction influenced your work on "Visions, Ventures, Escape Velocities"? What kinds of stories about space exploration did you want to edit and publish for the book?

A: One major inspiration for this book is Kim Stanley Robinson, our writer-not-in-residence this year at the Center for Science and the Imagination. We were especially pleased to link this project with the 25th anniversary of his seminal novel "Red Mars," which we’ve quoted from in a series of epigraphs throughout this new collection. Robinson has been writing technically grounded, optimistic visions of humanity in space for decades now, and we were hoping for stories that follow his example. And, of course, I was hoping for weird new tales that are unlike anything we’ve seen before. I’m happy to say there’s something rich and surprising to me in every story in the collection, from movie-buff AIs to plant pheromones that can hack human DNA.

“Visions, Ventures, Escape Velocities" is free to download in a variety of digital formats. Print-on-demand copies are also available for purchase, at cost, for $20.90, plus sales tax and shipping. Visit csi.asu.edu/books/vvev to learn more.

Top image: An illustration of one of the stories featured in "Visions, Ventures, Escape Velocities." Image by Maciej Rebisz

More Science and technology

ASU-led space telescope is ready to fly

The Star Planet Activity Research CubeSat, or SPARCS, a small space telescope that will monitor the flares and sunspot activity of low-mass stars, has now passed its pre-shipment review by NASA.…

ASU at the heart of the state's revitalized microelectronics industry

A stronger local economy, more reliable technology, and a future where our computers and devices do the impossible: that’s the transformation ASU is driving through its microelectronics research…

Breakthrough copper alloy achieves unprecedented high-temperature performance

A team of researchers from Arizona State University, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Lehigh University and Louisiana State University has developed a groundbreaking high-temperature copper alloy…