After 10 years, three changes of major and two children, Ashley Pitman graduated from college this week — the first in her family to earn a degree.

Like many first-generation students, her journey took a bit longer, but she knows that she’s secured a future for herself and her family with her bachelor’s of nursing degree from Arizona State University.

“One of the main reasons I did it is because I think each generation of family should improve themselves and strive for higher achievements,” the Navy veteran said. “Even having two kids in the middle of it, I still did it.

“I don’t think my kids will have an excuse to not go to college now.”

Pitman is part of a growing number of first-generation students accepted to and graduating from ASU, part of the university’s mission to expand access.

In the fall 2017 semester, 22,070 students — including first-time freshmen and transfers — were the first in their families to go to college. That's 26 percent of the total enrolled student population, compared with 18 percent a decade ago. And their graduation rate is on the rise.

First-generation students can face unique challenges in navigating the complex world of higher education, but graduation is critically important as Arizona tries to increase the number of degree-holding residents as a way to draw business and boost the state’s economy.

A degree makes an enormous difference. College graduates not only have lower rates of unemployment than non-degree-holders, they also earn an average $17,500 more per yearA recent study by the Pew Research Center found that the median yearly income gap between high school and college graduates is around $17,500. Another recent study from Georgetown University found that, on average, college graduates earn $1 million more in earnings over their lifetime. than high school graduates. Graduates are also more likely to vote and to live a healthier lifestyle.

ASU has committed to removing barriers to higher education and to supporting first-generation students with specialized coaching, which improves the odds that they’ll persist in their studies and graduate.

“We’ve proven that ASU’s vision is possible,” said Kevin Correa, associate director of ASU’s First-Year Success Center.

“We can be committed to both access and excellence at the same time. Those things are not mutually exclusive.”

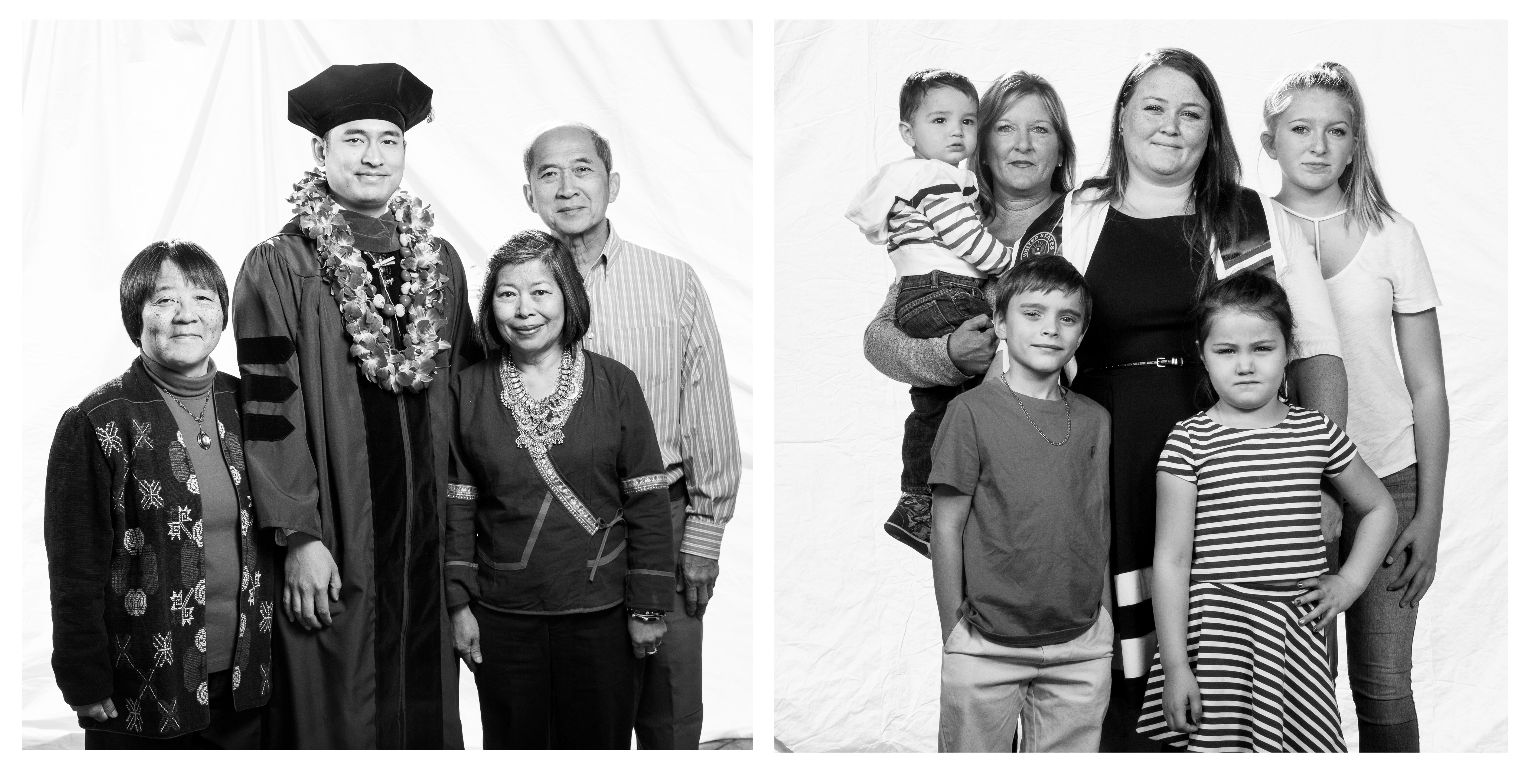

Sustainability doctoral graduate Michael Sieng (left) and Navy veteran and nursing graduate Ashley Pitman (right) stand with their families, of whom they are the first university graduates.

A blessing and a burden

ASU has supported students through its First-Year Success Center coaching program for several years, but two years ago, the university launched Game Changers, an initiative specifically focused on first-generation freshmen. These students get one-on-one counseling from older peer coaches, many of whom also are first-generation students, along with group events and advice on building practical skills, like time management and how to email a professor.

Game Changers validates the students’ experiences, according to Marisel Herrera, director of ASU’s First-Year Success Center.

“It’s the identity of ‘first.’ What happens when you’re the first in anything? There’s a huge learning curve because you have experiences that those around you have not had,” she said.

Students learn not only practical information specific to ASU, like how to work the meal plan, but they meet a community of people like them.

“We have faculty who were first-generation students come and give talks,” Correa said. “They become role models for the students to relate to and aspire to.”

Beyond practical advice, Game Changers recognizes the unique pressures that first-generation students face, Herrera said.

“You can be this awesome student, academically qualified, living the dream that you and your family have worked so hard for, but you still feel somehow like you don’t belong or you have to prove yourself in ways different from others,” she said.

Even with family support, there can be stresses.

“You have a great deal of expectation from those around you, including your family and your community, to succeed — which is a blessing and a burden,” Herrera said.

“So many times we see students who are doing great but they’re dealing with a level of stress that’s pretty high because this is not just about them and their 18-year-old world. This is: ‘I need to make my family proud.’ ”

Herrera said the Game Changer coaches approach the first-generation students’ experiences as positives, not negatives.

“We talk about them being trailblazers. We congratulate them for being courageous pioneers for their family. We celebrate the experience and ask them to reflect on it,” she said.

Game Changers coaches also push the freshmen to maximize their college careers with leadership positions, undergraduate research, study abroad or entrepreneurship.

“We want them to elevate their vision of themselves,” Herrera said.

The intense one-on-one help is unusual, and colleges from around the country call Herrera to ask about the model.

“For ASU to be the largest university in the nation and to offer such personalized support is unheard of,” she said. “We’ve demonstrated that you can care deeply at scale.”

Time for a culture change

When a family launches someone into college, that student often supports those who follow.

Tomy Gates graduated with a degree in community sports management this week, and his twin brother, Tommy Gates, will earn his degree in tourism development and management in May.

“We were pushed to graduate from high school, but college was never spoken of in our house,” Tomy Gates said.

The two eventually enrolled in community college in their home state of California, and then Tomy Gates transferred to ASU.

“He helped me with everything,” Tommy Gates said of his brother. “He transferred first. He said, ‘This is what you need to do. This is how it will work. It’s a load you can carry, and I know you can do it.’ I’ve been looking up to him since I got here.”

The two, who live together while attending classes on the Downtown Phoenix campus, said that even though they were never encouraged, they knew they wanted degrees.

“It’s time for a culture change, and that’s what we wanted to do,” Tommy Gates said.

“We knew we could do it. We weren’t pushed to be doctors, but we knew we had the skills to graduate and change everything around us and make a better environment.”

Laura Samora was the first in her family to get a degree when she graduated from ASU in 2009, and this week, she watched her husband, Frank Samora, also a first-generation student, earn his degree in kinesiology.

“With us it’s really been a team effort with his working full time and going to school full time,” she said. “It’s been incredible to see all the personal growth in him, and the finish is almost bittersweet.”

Frank Samora, who’s a Marine Corps veteran, said his wife “got him over the finish line” and that he bonded with other first-generation students.

“We helped each other to reduce the anxiety. ‘First time you, first time me,’ ” he said.

Young people whose parents did not finish college are less likely to enroll in higher education right after high school. So for many, the journey to a degree is a long one.

Stacey Lynch earned her psychology degree from ASU Online this week, 20 years after graduating from high school. Along the way, she married and had seven children.

“My parents never encouraged me to go to college,” she said. “They said, ‘Find a good man to support you and have his babies.’ ”

Lynch worked for several years before enrolling in a community college in her home state of California.

“It was really hard because I did it all by myself. A lot of people have financial support and the backing of their parents, and I didn’t have that,” she said.

She had to work up the courage to apply to ASU Online two years ago and didn’t even tell her husband until a week after she was accepted.

“I told him, ‘I really want to finish this,’ ” said Lynch, whose children range in age from 18 years old to 4 months.

Her husband, Joe Lynch, is starting a master’s program in ASU Online this spring.

“She inspired me. It was so hard, and she did so much homework and she had a baby in her senior year,” he said, adding that their son and six daughters all will attend college.

Stacey Lynch, who will begin the master’s of social work program through ASU Online next fall, said that her degree means she’ll always have the ability to provide for her family.

“It’s changed my life.”

More Sun Devil community

Stellar student finds friendship is the best algorithm

They were two retired neighbors, dogs at heel as the evening sun slanted over Hayden Lawn, watching the students in the AZ Saber club swagger and spar with glowing lightsabers. Dave Mills and…

5 years young: Mirabella at ASU keeps redefining lifelong learning

Mirabella at ASU celebrated its fifth anniversary on Jan. 22 with a progressive dinner party for its nearly 400 residents, marking how far the university-based retirement community has come since…

2026 MLK Servant-Leadership Awardees announced

Every year in honor of Martin Luther King Jr.'s legacy of leading through service, Arizona State University recognizes members of society who are upholding the civil rights activist's ideology and…