ASU students learn from the dead at Teotihuacan

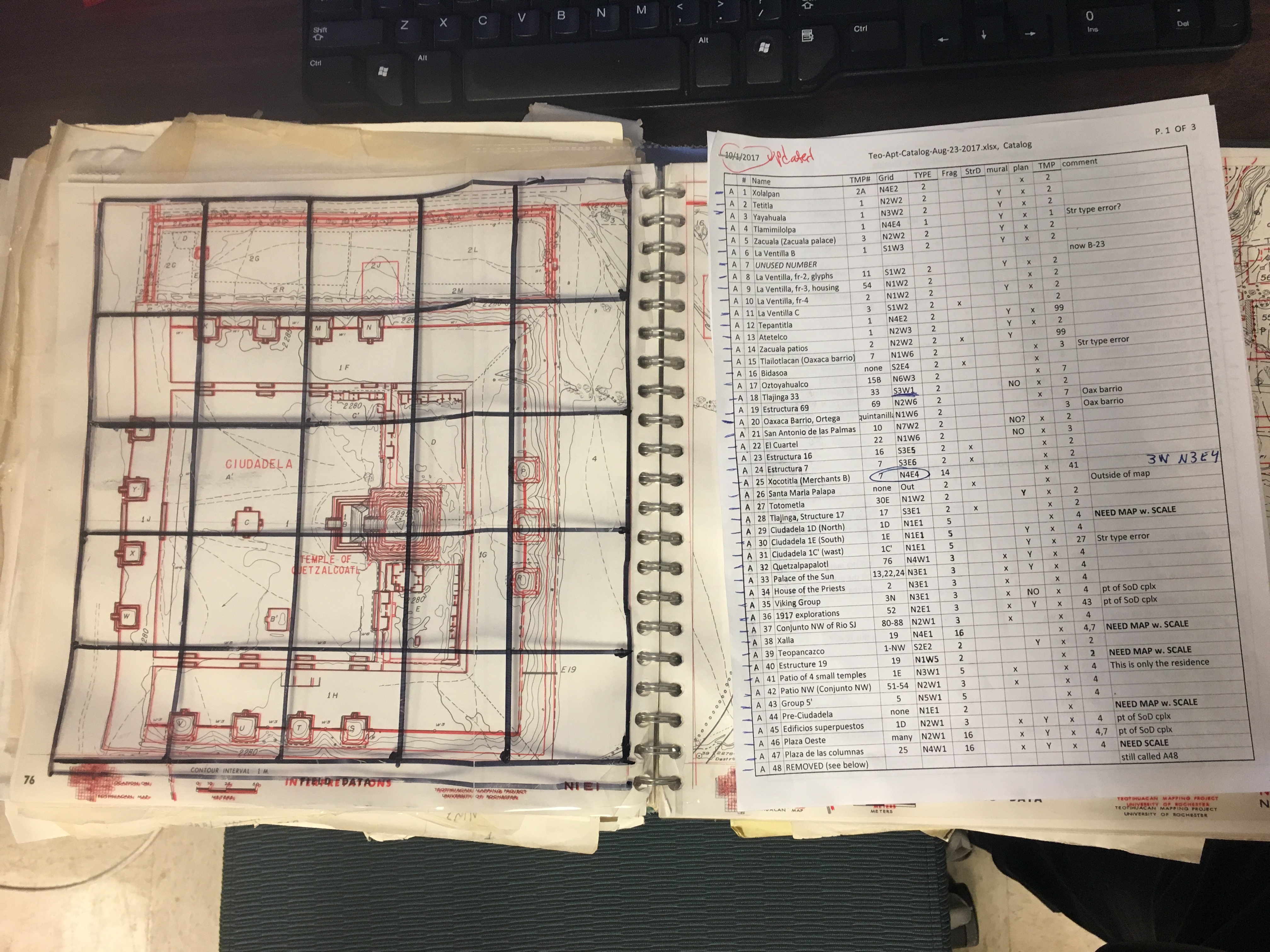

Intern Noah Livingston looks at the Teo Mapping Project, pointing with a piece of obsidian.

Teotihuacan was once the largest and most influential city in the ancient new world. Yet its social structure seems to be more egalitarian than those in its fellow ancient cities.

“Most ancient societies had an elite class that lived in big houses and had big fancy tombs. Then you got the commoners living in little houses and their burials were very simple with no gravestones,” said Michael E. Smith, a professor in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change at Arizona State University. “You don’t seem to have that distinction at Teotihuacan.”

Mesoamerican expert and archaeologist Smith is the director of the Teotihuacan Research Laboratory, an ASU-managed facility for on-site archaeological fieldwork to further understand ancient urban life. Smith is leading the lab’s new project, “Burials and Society at Teotihuacan.”

“At Teotihuacan, the standard residence was 10 times as big as an Aztec peasant house,” Smith said. “There’s something strange about the level of inequality being lower, and there seems to be a lot of prosperity. So maybe the burials will provide another perspective on this because we don’t have a good handle on how society was organized at Teotihuacan.”

A team of undergraduate students will be creating a database of the burials and offerings from the city, which has never been done before. They will analyze patterns of wealth, status and gender within the burials.

“I’ve always worked pretty heavily with undergrads,” Smith said. “I like working with undergrads because they’re just figuring out that they can do something beyond just learning knowledge from a book or from a class. I think the kinds of experiences and skills they’re getting are valuable in lots of ways.”

A picture of the Teotihuacan Mapping Project, a collection of maps of Teotihuacan and the structures

The students' potential discoveries can contribute to studies of our modern world, such as alternative governmental systems, how cities rise and fall, and the ways social practices change over time.

“No one has really looked at burials systematically, and we can learn a lot of things from the data of what was excavated,” Smith said. “It’s a source of information that hasn’t really been exploited.”

Emily Edmonds, an undergraduate student studying anthropology in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change, is one of the students working on the research project. She processes the documentation side of the project by reading the materials that have been written on the burials already and using them to help guide the group’s data analysis.

“The project is probably going to go in a couple of different directions as we figure what, exactly, we are looking for,” Edmonds said. “Just doing some of this data analysis, I’m noticing we should be looking for certain things, or we need to fix a variable within it, and I think it’ll be really exciting when we get our own data.”

Another undergraduate working on the documentation portion of the project is Noah Livingston. As an anthropology student, he is grateful for the skills he is learning within the lab because he knows will help him in his future career.

“I’ve already gained a lot from this project,” Livingston said. “I find our research and Teotihuacan itself tremendously fascinating. I also enjoy being able to apply what I’ve been learning in my classes to a real archeological project. I get to gain experience in working on long-term research, from design onward.”

The project will continue into the spring semester with the undergraduate students compiling a comprehensive catalog of residential burials and their associated offerings at Teotihuacan.

“It’s sort of an experiment,” Smith said. “A project that is, in large part, run by undergraduates. I think the experience of doing research is really helpful because you’re not just learning something and remembering something; you have to figure out how things work and how to evaluate things, and it just has lots of aspects of learning an experience.”

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU course explores culture through an interdisciplinary lens

When Razieh Araghi joined Arizona State University in fall 2025, she wanted to show students the power of humanities. Her…

ASU launches ‘AI-Informed Writing Classroom’

“How do I know what I think until I see what I say?”This question, attributed to novelist E.M. Forster, alludes to the role…

Fluent Futures Lab teaches what English textbooks miss

Learning English is about more than mastering key vocabulary and demonstrating verb tenses — it’s about knowing what to say…