New ASU course will look at fake news, alternative facts through the ages

According to Arizona State University Assistant Professor Sarah Viren, “fake news is nothing new, and alternative facts were around long before they were given that name.”

Viren is teaching a new English course in spring semester 2018 that will put the falsification of truth in historical contexts and offer lessons for how we can become better users of information today.

“We’ll cover some of the earliest examples of fake news — including an invented history by a Byzantine historian — alongside more recent hoaxes, from fictionalized memoirs to bogus news accounts of life on the moon,” said Viren (pictured above, right), assistant professor of English and creative writing in the Languages and Cultures faculty of the College of Integrative Sciences and Arts. “Within this context, we’ll also look at the evolution of factuality as a concept and map its relationship with literature and news, both fictional and not.”

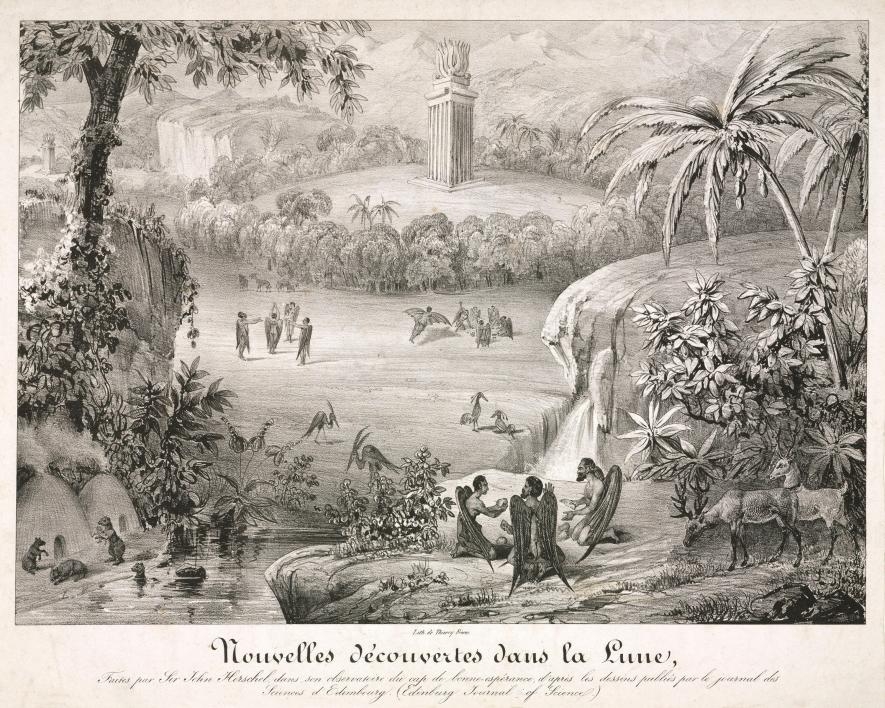

Even those who are unable to take her course might enjoy, and learn something from, one of the readings — what has come to be known as the Great Moon Hoax of 1825.

The piece was printed in six installments in the New York Sun newspaper over one week and written by a fictionalized Dr. Andrew Grant, who maintained he’d been hired to make an account of the astronomical observations that Sir John Herschel was making with a magnificent new telescope.

The details shared seem utterly preposterous to us today.

There were luxuriant forests, barren prairies, blue oceans, white-sand beaches. There were miles of wine-colored amethyst quartz formations and temples built of polished sapphire. The account described exotic lifeforms: bison who, by wiggling their ears, could move a flap of skin from their forehead down to cover their eyes; goats with a unicorn-like horn; biped beavers who glided along the ground carrying their young in their arms; and winged humanoids characterized as man-bats, who “spent their happy hours in collecting various fruits in the woods, in eating, flying, bathing and loitering about on the summits of precipices.”

The story went viral, 19th-century style.

“Subscriptions doubled within days,” Viren said. “People were lining up outside the newspaper offices waiting for the next installment.”

Why was it such a sensation?

“Like a lot of the fake news today, the story had the veneer of truth; it even claimed to be a reprint of findings from a scientific journal,” she noted. “And hoaxes like that weren’t uncommon then. The writer Edgar Allan Poe published his own invented news in the New York Sun sometime later, though his was a little more believable. It told the story a man who crossed the Atlantic in a hot-air balloon.”

Viren, who worked as a journalist for six years before she completed a master of fine arts in creative nonfiction at the University of Iowa and a doctorate at Texas Tech University, said the impetus for the course grew out of a panel proposal that she and another colleague worked up for the March 2018 AWP conference, titled “The Facts About Alternative Facts.”

“We’re both experts in nonfiction, and we study the essay and other forms of writing,” Viren continued. “We thought we had an obligation to dispel the notion of fake news being a modern phenomenon and could bring some nuance and history to the discussion. As I started thinking about the ways we might talk about factuality that‘s contemporary and historic, I thought, 'Hmm, I think this is a class.' ”

The idea of “fact,” Viren noted, is a relatively modern phenomenon.

“In ancient Greece, oracles were considered a form of truth and so when a guy named Onomacritus forged oracles and tried to pass them off as real, he was in a sense publishing fake news. There’s also an example of a Roman-era historian who invented history. And the writings of someone who claimed to be a disciple of the apostle Paul, but wasn’t, managed to influence Christian thought throughout the Middle Ages,” she said.

One of the texts students will examine during the first part of the semester is “Robinson Crusoe” by Daniel Defoe. Published in 1719, it blurred the boundaries of truth and fiction.

“Today we think of ‘Robinson Crusoe’ as literature, as a novel,” explained Viren. “But when it came out, works like this were talked about —and read by some — as if they were nonfiction, until they became their own genre.”

Students in the course will read examples of “yellow journalism” prominent in the U.S. of the late 1800s, the false or exaggerated reporting that newspapers frequently used to try to lure more readers, and then the focus will move on to more contemporary publications and podcasts.

“We’ll look at at least one falsified memoir,” said Viren, like the recent "A Million Little Pieces" by James Frey, once an Oprah's Book Club title.

“(Oprah) Winfrey brought Frey back on her show to confront him after the falsifications had been revealed, accusing him of cheating and harming his readers by giving this false story,” she said. “There have been lawsuits against him, which is odd, considering there’s usually no actual harm to someone from reading a fictionalized memoir. But the way we read is different when we decide something is true,” she continued. “The way we make meaning for ourselves is different if we think what we’re reading is fiction.”

Students will eventually find their own examples of fake news and compare them with examples from the class, so they can contextualize what they see today with fake news from the past — and think about their present-day consumption of information as well.

Viren, who joined ASU this fall, has always had a fondness for storytelling.

She started her journalism career at a weekly newspaper in Florida, on a tiny island of 3,000 people.

“I rode a golf cart around and reported on anything and everything that was going on,” Viren said with a laugh. “By the time I’d left, it felt like I’d written about just about everybody! I came away understanding that there are stories to be told about anyone and everything.”

From there she moved to the Galveston County Daily News, where she focused on the police beat, city council and other county news. After writing investigative stories for the Corpus Christi Caller-Times, often doing data-based reporting about social issues and juveniles, she was hired by the Houston Chronicle in 2006 to cover youth affairs.

Her transition from award-winning journalist to university professor has brought publication success as well.

Ploughshares Solos published Viren’s translation of the Argentine novella “Córdoba Skies,” and her first essay collection, “Mine,” won the River Teeth Literary Nonfiction Book Prize and will be published in 2018.

Her new course, which will be offered on ASU’s Downtown Phoenix campus, is open to any students who might have interest, Viren said, but she noted that it might be especially appreciated by majors in English, history, philosophy and journalism.

“It’s my very favorite kind of class to teach,” she said, “where you’re evaluating literary texts and you’re going to be able to dig into important questions with the students as you move forward.”

This ENG 494: Special Topics course "Fake News and Alternative Facts: A Survey Course" (registration code #30441) will meet from 4:30 to 7:15 p.m. Tuesdays in the spring 2018 semester, in the University Center Building on ASU’s Downtown Phoenix campus. Top photo: Award-winning journalist Sarah Viren is now an English professor in the College of Integrative Sciences and Arts at ASU. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

More Law, journalism and politics

Can elections results be counted quickly yet reliably?

Election results that are released as quickly as the public demands but are reliable enough to earn wide acceptance may not always be possible.At least that's what a bipartisan panel of elections…

Spring break trip to Hawaiʻi provides insight into Indigenous law

A group of Arizona State University law students spent a week in Hawaiʻi for spring break. And while they did take in some of the sites, sounds and tastes of the tropical destination, the trip…

LA journalists and officials gather to connect and salute fire coverage

Recognition of Los Angeles-area media coverage of the region’s January wildfires was the primary message as hundreds gathered at ASU California Center Broadway for an annual convening of journalists…