In 1980, the city of Tucson and the Arizona Department of Water Resources began an ambitious plan to replenish Tucson’s depleted aquifers. By 2004, the city had implemented water conservation practices among its residents and had begun using Colorado River water to recharge its aquifers. By 2015, Tucson was able to show a significant increase in water storage in the city’s aquifers, a vital element to this thriving city.

Arizona State University geophysicists Megan Miller and Manoochehr Shirzaei, of the School of Earth and Space Exploration, along with Donald Argus of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology, were intrigued by Tucson’s water storage success and wanted to take a closer look at what was happening both above and below ground.

“We chose the Tucson area because the groundwater management and conservation challenges there offer lessons for many other cities in the Southwest with similar predicaments,” Miller said. “Tucson was also of special interest because, contrary to what would be expected, its aquifer levels did not dramatically decrease during a period of drought.”

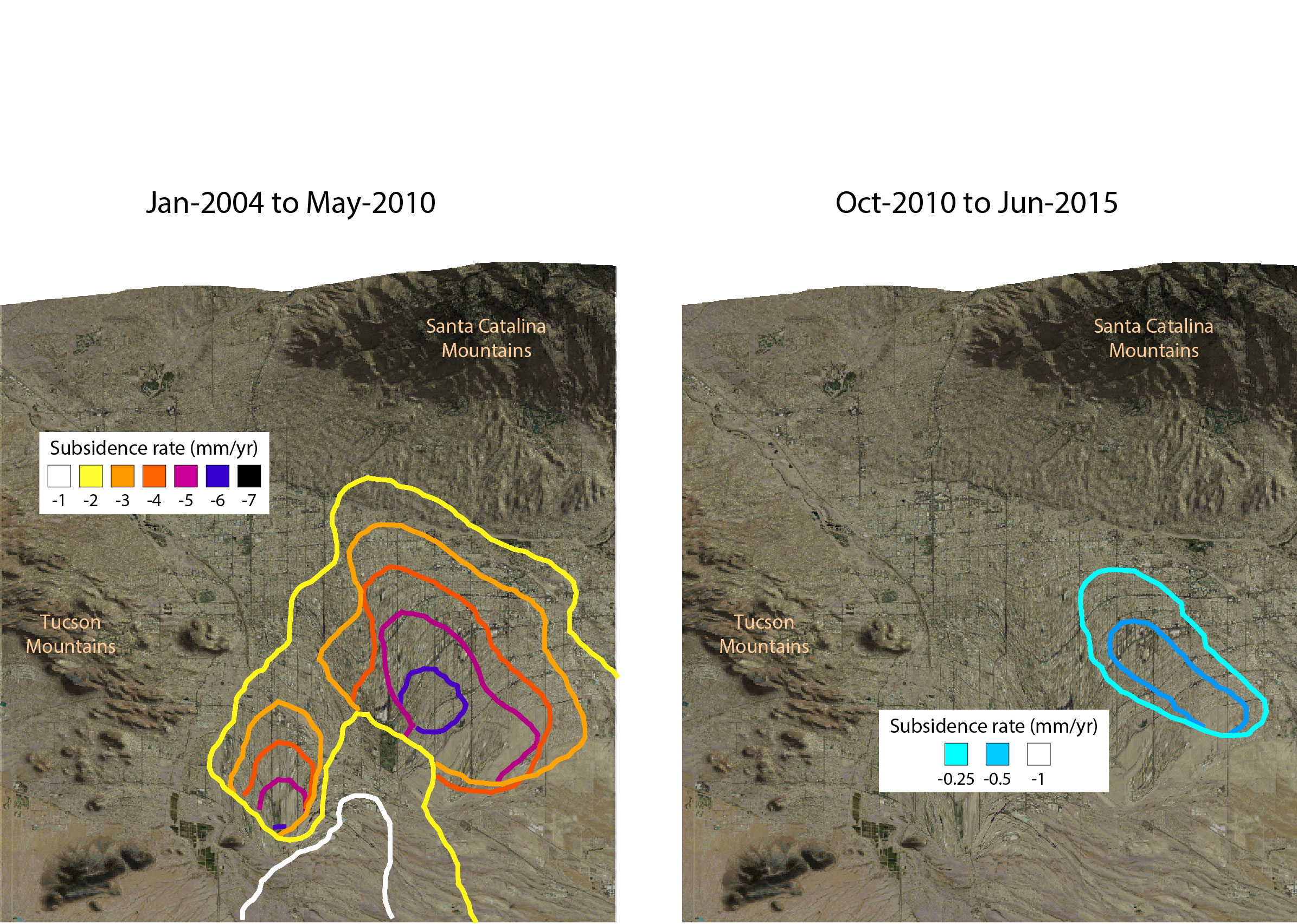

To study the area, the researchers used satellite radar data from the Envisat and RADARSAT-2 satellites from 2004 to 2015. Using this data, the researchers tracked land subsidence and measured how much the land fell, rose or stayed the same over time. They then compared the satellite-derived subsidence data to measurements from global positioning systems, land thickness studies and well levels.

The results of their study, recently published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, showed that following Tucson’s water conservation and management efforts, not only did the land subside less, there was also a decrease in the loss of storage volume in the aquifer.

Left image: Vertical land motion (mm/yr) in the Tucson metropolitan area observed using Envisat InSAR 2004–2010. This image depicts, through satellite data, how fast the land in the area of study was moving downward from 2004-2010, during which the Tucson area aquifer experienced storage volume loss. Right image: Vertical land motion (mm/yr) observed using RADARSAT-2InSAR 2010–2015. This image depicts how fast the land was moving downward during a significantly slower period when volume loss had been minimized as a result of groundwater management and conservation efforts. Credit: Megan Miller/Manoochehr Shirzaei

So far, artificial recharge efforts in Tucson have banked the equivalent of at least 45 years of groundwater withdrawals needed for residents of the area. When combined with impressive conservation efforts, Tucson has been able to minimize land subsidence, halt the depletion of the aquifer storage, and store water for the future.

The researchers hope that understanding how Tucson succeeded in storing water for the future may help other Southwestern cities.

“Knowing how the aquifer system responds can help public-policy makers decide what to do in the case of a water shortage,” Miller said. “In particular, knowledge of an aquifer’s elastic properties would allow authorities to determine how much fresh water can be extracted without causing permanent damage to the aquifer system.”

Top photo: Tucson skyline. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

More Science and technology

Hack like you 'meme' it

What do pepperoni pizza, cat memes and an online dojo have in common?It turns out, these are all essential elements of a great cybersecurity hacking competition.And experts at Arizona State…

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive — under pressure.One such innovation is the newly released tomato variety…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper fish. Nearby, children chase bubbles and move to music, while…