Buildings account for 46 percent of all carbon emissions. They also account for 75 percent of all electrical use.

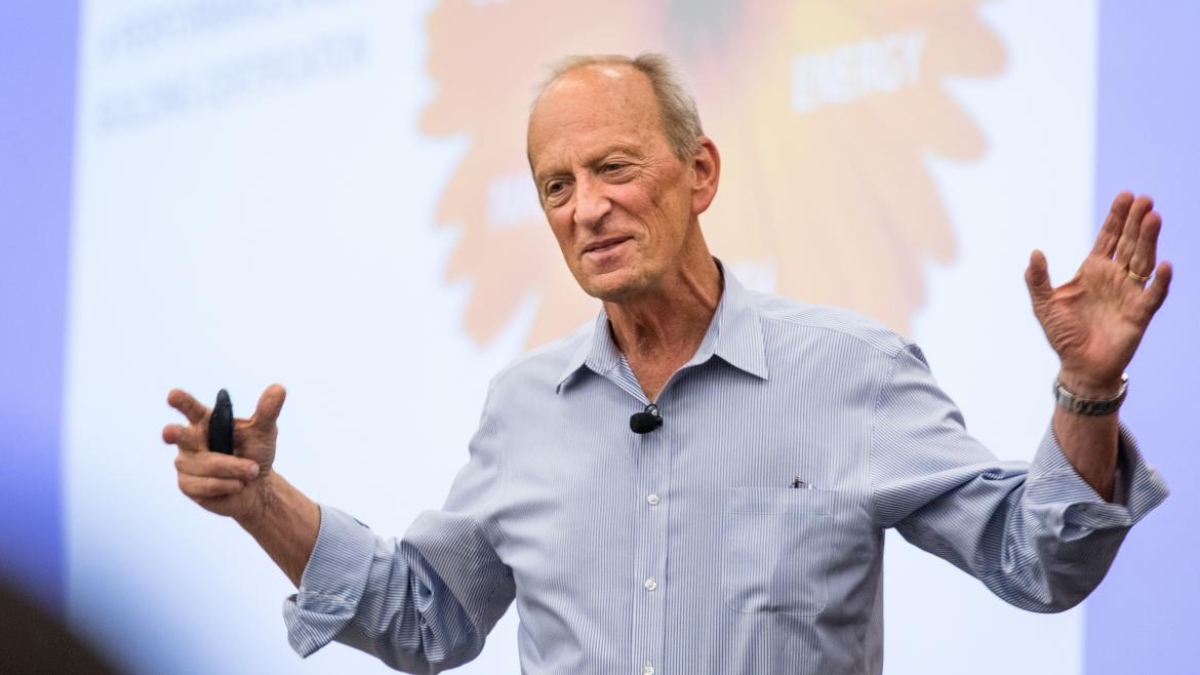

“This is breathtakingly important,” Denis Hayes told an audience at Arizona State University on Monday night.

Hayes, coordinator for the first Earth Day and president and CEO of the Bullitt Foundation, a nonprofit devoted to protecting and restoring the environment of the Pacific Northwest, discussed working in what has been described as the world’s greenest building.

The Bullitt Center in Seattle has met what is called the Living Building Challenge. A combination of a building standard and a philosophy, it’s similar to LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) certification, but performance-based.

LEED buildings can be “heroically disappointing,” Hayes said, citing a new Seattle City Hall that is LEED-certified but has more of an environmental impact than the old building it replaced.

“We need to move vastly farther and vastly faster,” Hayes said.

A Living Building must produce 105 percent of the energy it uses. It must capture its own water. It cannot have been built on a place where nothing has been built before. And it must not use materials from a banned “Red List” that are hazardous to human health or the environment.

The Bullitt Center has produced 60 percent more energy than it uses during the past three years.

“To which the basic question arises: What’s up, Phoenix?” Hayes said. “In Seattle we don’t even know what the sun looks like.”

He called the building the most comfortable office building in Seattle. Windows crack themselves automatically around 9 p.m., letting cool night air to circulate. At 7 a.m., they automatically close.

The water goal was to operate with as much impact as a Douglas fir forest on the same site. A study revealed it uses slightly less water. Composting toilets use a half cup of water per flush. A traditional low-flow toilet uses 1.5 gallons per flush.

All of this sounds expensive. The six-story building cost $355 per square foot, less than the median cost of construction of Class A office space in Seattle. One way this was achieved was to have no marble, no granite countertops, no expensive art and no parking garage. (Workers bike, take public transit or Lyft, or they park a block away.)

The idea in bringing Hayes to speak on campus was to spark ideas about possibilities, said Mick Dalrymple, directorDalrymple is also a senior sustainability scientist at the Julie Ann Wrigley Global Institute of Sustainability and an instructor in the School of Sustainability. of University Sustainability Practices at ASU.

“Most people don’t know what a living building is, so I wanted to elevate the conversation here and get people to think of a new idea,” he said. “I don’t expect that ASU is going to have some Living Building Challenge policy. It’s really made for design for the frontier buildings, people who really want to push the envelope.”

The new Student Pavilion (and the newly renovated Orange Mall in front of it) hosted Denis Hayes on Monday evening. The Student Pavilion was designed to be ASU's first Net Zero Energy building. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

Dalrymple and his University Sustainability Practices team help the university reach its ambitious sustainability goals. ASU owns the largest number of LEED-certified buildings in Arizona and built state's first-ever LEED Platinum building, the Biodesign Building B on the Tempe campus.

A Living Building earns certification after one year, during which all metrics are measured.

“It’s a pretty tough standard,” Dalrymple said. “It’s tougher than LEED. It’s not based on design. It’s based on actual performance.”

The water standard for a Living Building would be very tough to achieve in dry, sunny Arizona. But incorporating other standards is possible, Dalrymple said.

“There are a good number of people within ASU looking into the Living Building Challenge to see how we might be able to do a Living Building or at least is inspired by or aspires to the Living Building Challenge,” he said. “I am hoping we get one or two of them here; specifically I’m hoping that we go for it on ISTB7, and maybe on Waterworks, although on both of them it’s an extremely challenging standard to meet. I don’t know if it’s possible or not, but I want us to explore it and see how far we get. It’s really kind of an aspirational thing.”

Hayes cited the 50th anniversary of Earth Day approaching in 2020. A movement like that had to have incredible tailwinds, he said.

“And that begins at universities,” he said.

The Julie Ann Wrigley Global Institute of Sustainability sponsored Hayes' visit, along with other partners. For more GIOS events related to Campus Sustainability Month, click here.

Top photo: Earth Day coordinator Denis Hayes speaks about Living Buildings at ASU's new Student Pavilion on Monday evening. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

More Environment and sustainability

'Earth Day Amplified' promotes power of collective action

Everybody loves the concept of sustainability. They want to do their part, and the chance to say they’ve contributed to the well-being our of planet.But what does that actually mean?Arizona State…

Rethinking Water West conference explores sustainable solutions

How do you secure a future with clean, affordable water for fast-growing populations in places that are contending with unending drought, rising heat and a lot of outdated water supply infrastructure…

Meet the young students who designed an ocean-cleaning robot

A classroom in the middle of the Sonoran Desert might be the last place you’d expect to find ocean research — but that’s exactly what’s happening at Harvest Preparatory Academy in Yuma, Arizona.…