A tale of two families

Diana Hinojosa DeLugan sat outside on a bench at her home in Tempe, peeling away layers of newspaper from a package as the early evening light faded behind her. Slowly, two 45 RPM vinyl records emerged. They were her father’s, recorded in the 1960s when the jarochoThis is a regional folk musical style from Veracruz, a Mexican state along the Gulf of Mexico. musician was in his 30s. Hinojosa DeLugan had packed them away after his funeral services 20 years ago — this was the first time she’d seen them since. Almost immediately her eyes began to well and she brought a hand to her lips.

“I didn’t want to open them until they had a good home,” she said.

•••

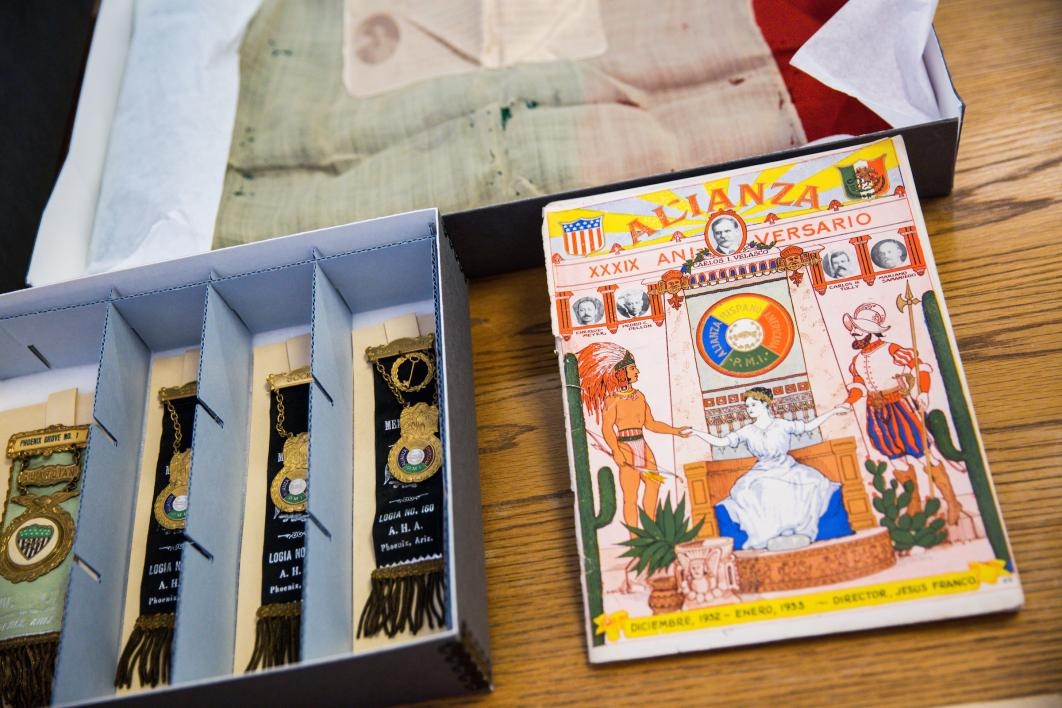

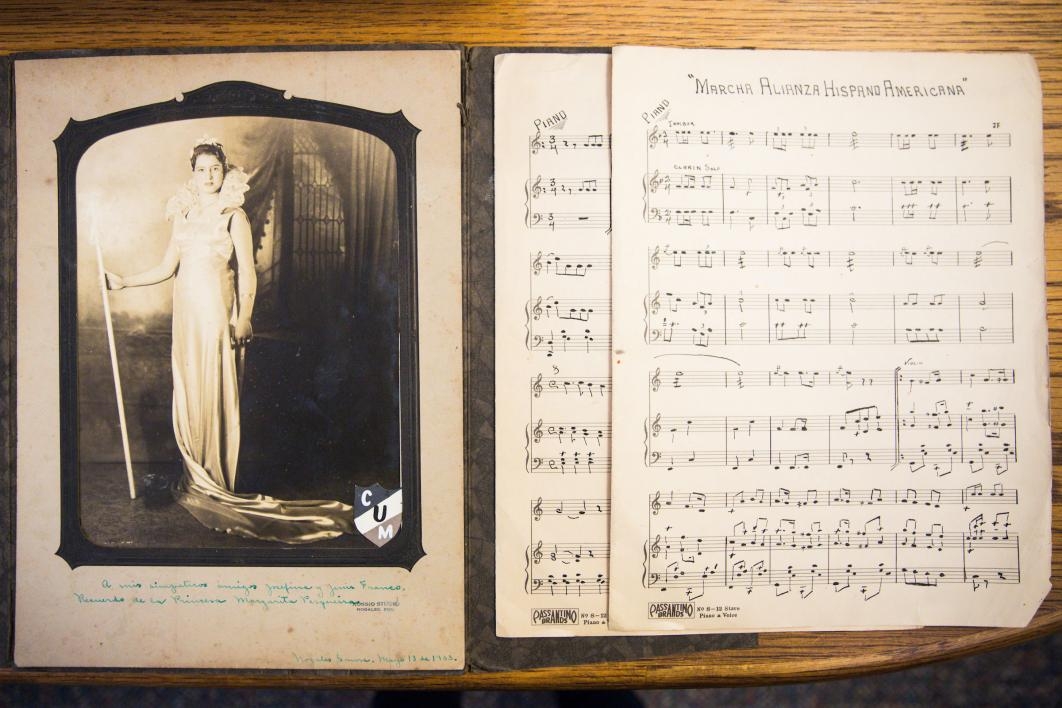

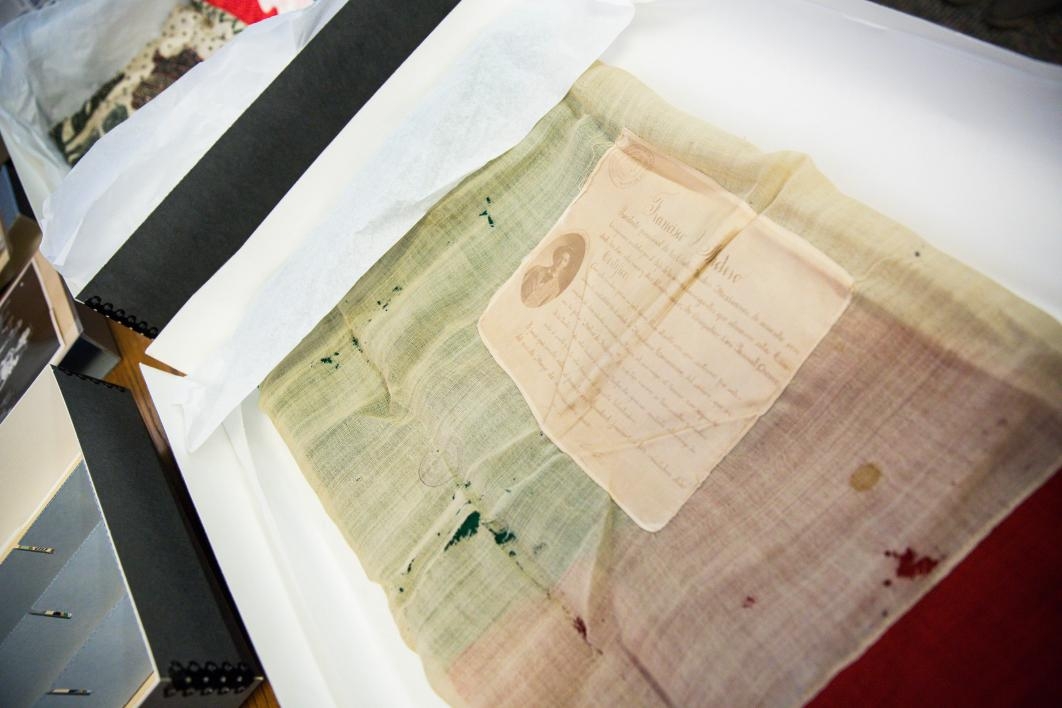

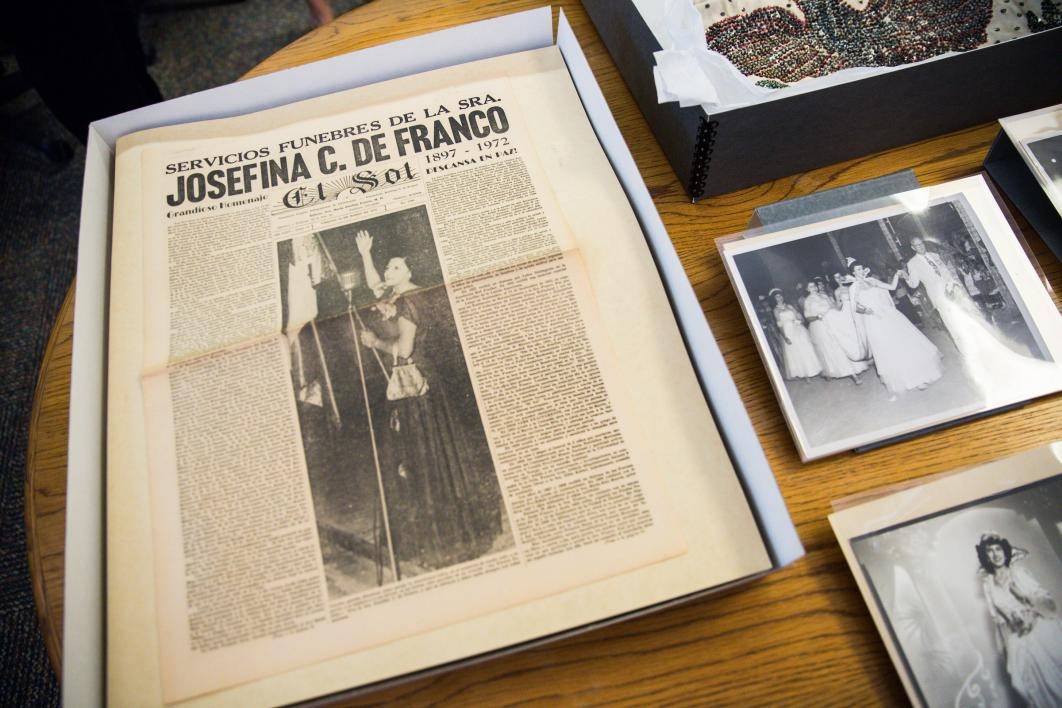

Laura Franco French surveyed the items laid out before her. A traditional "china poblana"-style Mexican skirt, shimmering with hundreds of painstakingly sewn sequins; a threadbare flag, the vibrant red, green and white stripes now faded and yellowed; a copy of the Spanish-language Phoenix newspaper El Sol, which stopped production in the 1980s. All of it Franco French found stowed away in her parents’ home after they’d passed.

“My mom saved everything,” she said. “But it wasn’t for me to keep all of this.”

•••

All of that and many more of the family treasures Hinojosa DeLugan and Franco French hold dear have finally found a home befitting their historical significance, among the archives in ASU Library’s Chicano/a Research Collection. Both women will be honored for their contributions at a public ceremony at 6 p.m. Wednesday, Oct. 4, in ASU’s Hayden Library on the Tempe campus.

“Everything [in their collections] is of historic importance because everything relates to the building of what we now call the Mexican community of Phoenix,” former ASU archivist Christine Marin said. Though now retired, Marin helped facilitate their donations.

“If we want to look at the history of Mexicanos, or Mexicans in Phoenix, we have to look at families, their contributions, their professions, the things that they did to bring people together.”

ASU Library archivist and curator of the Chicano/a Research Collection Nancy Godoy has spent over a year processing, preserving and making the items donated from the Hinojosa and Franco French families publicly available via ASU Library's online portal.

“Family collections, for me, personally, are very important because they tell so many different stories,” she said. “So that’s priority for us, to make these collections accessible to the community.”

Video by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

Godoy is an expert in the art of preservation. Photos are placed in special Mylar sheets, and items like clothing and newspapers are placed in acid-free boxes and folders.

“This material will be here probably longer than most of us,” Godoy said, referring to a group of university staff gathered to receive the latest donation from Franco French. “It has a life expectancy of 50 to 100 years if you properly monitor the material.”

That’s great news to Franco French and Hinojosa DeLugan. It’s clear they spent a lot of time considering whether to part with their family heirlooms, and they’re glad to know the items will be available for students, researchers and the public for years to come.

“I’m so proud of the legacy of Mexican-Americans in Arizona that I wanted [these items] to be accessible to everyone and to have people honor the rich heritage that we have,” Franco French said.

Their stories are different yet the same.

Hinojosa

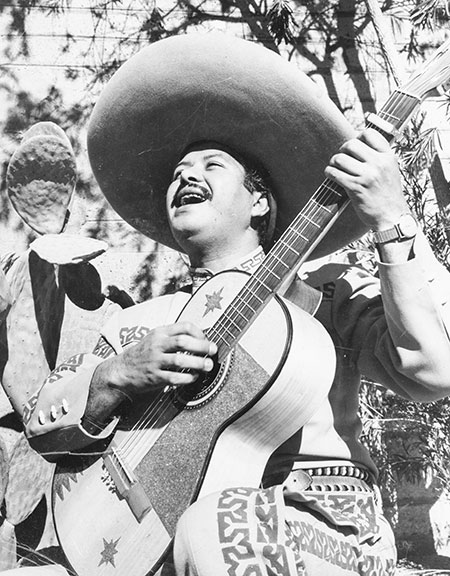

Musician Fidencio Garcia Hinojosa (second from left) was known for popularizing jarocho music in the Phoenix area during the middle of the 20th century. This photo of him and his bandmates is part of the collection of memorabilita and family heirlooms being donated by his daughter to the Chicano/a Research Collection at ASU's Hayden Library.

Hinojosa DeLugan is the daughter of beloved Veracruz-born musician Fidencio Garcia Hinojosa, known for popularizing jarocho music in the Phoenix area. She describes jarocho as “a fusion of Afro-Cuban, indigenous and true Spanish music,” usually accompanied by zapateado, hard-heeled dancing that acts as additional instrumentation to keep the beat.

Ritchie Valens' 1958 smash hit “La Bamba” is probably the most well-known example of the style, she said.

Garcia Hinojosa crossed the border from Mexico into Texas as a young teen in the 1940s seeking a better life after playing the guitar in a traveling circus. He adopted the name Hinojosa from the migrant worker family that took him in there. Before that, he would spend his days waiting for tourists to throw money into the Rio Grande and dive into the river to collect it as a means of survival.

Eventually, Garcia Hinojosa made his way to Phoenix, where he continued playing music. At one point, he was approached by a group of businessmen who were opening a restaurant near Scottsdale and McDowell Roads. They wanted a house band and asked him to be the leader of a group.

One of the items Hinojosa DeLugan donated is a document from the U.S. Department of Immigration, which the businessmen petitioned to bring the other members of the group in from Mexico. It states that they were the only group of traditional jarocho musicians in existence in the U.S.

“This is a unique music history because it’s not just music in general, it’s jarocho music,” said Hinojosa DeLugan, a singer herself. “Most people, when they think of Mexican music, they automatically think of mariachi, the big hat, the charro outfit. That’s kind of the icon of Mexican music. … So I thought it would be good for Arizona to remember this.”

She remembers being a child living in a house in an area of town known then as Las MilpasThe word “milpa” is derived from the Nahuatl word phrase mil-pa, which translates to “maize field.”, now the location of GateWay Community College Central City campus. At times, the house was brimming with the families of musicians who would visit to play with her father — and also brimming with their voices.

“A true jarocho has a way of singing their words,” she said. “It’s very different than what we know as colloquial Spanish. Even though I had never heard [my father] speak that way, it took him no time at all to go into singing his words.”

Meeting those HuastecaThe term “Huasteca” describes a person from a region of Mexico including the state of Veracruz, where Fidencio Garcia Hinojosa was from. families and hearing those voices opened a window into her father’s past, and thereby her own history.

“It was nice to learn about where my father was from, and his people,” said Hinojosa DeLugan, who was born in Phoenix.

Garcia Hinojosa performed all over the Valley, at large public events like the Fiestas Patrias, Mexican Independence Day celebrations, as well as small, intimate gatherings. Sometimes, like when he played for the former Gov. Raul Castro’s campaign events, his daughter would accompany him.

“To be able to play the music that was so unique. … For the Hispanic culture, it’s part of what brings us together as a people, as a tribe, as a clan,” Hinojosa DeLugan said.

As Fidencio Garcia Hinojosa went through the naturalization process, he meticulously saved every document: his naturalization papers, a copy of the Pledge of Allegiance, a novelty American flag. All of those items are now a part of the collection at Hayden Library.

She also remembers times in the Las Milpas home gathered around the table with her family after dinner, when her father would study to become a U.S. citizen.

“He’d study everything. Geography, everything to do with the U.S.,” she said.

As Garcia Hinojosa went through the naturalization process, he meticulously saved every document: his naturalization papers, a copy of the Pledge of Allegiance, a novelty American flag. All of those items are now a part of the collection at Hayden Library.

“To find all [of that] intact just showed me how much it meant to him” to be an American citizen, Hinojosa DeLugan said.

Her father also studied Mexican songbooks. He’d never spent a day in school and didn’t know how to read or write Spanish or English, so that was how he learned, she said. The songbooks also told the history of the music and what inspired it. Before he passed, he put all of them in a big, brown suitcase and gave them to his daughter.

“I opened it up, and there were 80-plus songbooks,” Hinojosa DeLugan said. They dated from the late 1940s through the 1990s. She has since added several more to the collection, dating as far back as 1914.

“These songbooks are a tremendous wealth to so many people,” she said, because they tell the story of the history of Mexico through lyrics.

And then there are the letters, nearly a decade's worth. Letters from her father to his family, from his family to her father. After he left Mexico, he only ever saw them once, for a brief visit in the 1970s. Hinojosa DeLugan had reservations about including the letters in the collection because they were so personal. She tells of reading her grandmother’s words and feeling the “angst, sadness and loneliness.”

After some reflection, she decided to include them “specifically because my father was just like so many other people. ... He was an immigrant. And so many immigrants face the exact same thing. The struggles of the loss of their families, the desire to want to be with them and they can’t. The desire to want to help and they can’t. … I want people to know that this is a true story for so many immigrants.

“This is the face of an immigrant who came [to the U.S.] … and achieved his goal [of becoming a citizen], and the truth of what it meant to him to be so proud of that.”

Hinojosa DeLugan said she wants people to know her father’s story because it shows that “you can love where you came from, you can love the culture, which he did, he was passionate about it, his identity was being a jarocho musician. You can have that, but you don’t have to lose it to become a U.S. citizen.”

“His life was straddling both borders,” she said. “We lived, breathed and sang Mexico, spoke Spanish, ate Mexican food, danced Mexican dances, sang songs from Veracruz. Yet, just as important was, ‘Don’t forget, it’s time to vote! This is your duty as a citizen.’”

She still performs with her band, Rhythm Express, two or three times a month at various spots around Phoenix. And she still thinks of her father every time.

“He was so much of what became my identity as a human being,” she said. “To this day, when I perform songs, I stand there singing and I’m thinking of my dad, of the songs we used to sing together.

“I’ll always be his jarochita.”

Franco French

An image of the Fiestas Patrias in Phoenix from the Franco French family collection being donated to the ASU Library. Laura Franco French's grandparents brought to Phoenix the tradition of Fiestas Patrias “queens,” a custom at the celebrations in Mexico.

Laura Franco French never met her grandparents but, she said, “It was as though I did because my mom kept them alive always” through stories and pieces of the past she kept.

Her grandfather, Jesus Franco, served as the consul generalThe consul general is the highest-ranking consul among those consuls serving as representatives of the government of one state in the territory of another. from Mexico to Arizona. His wife, Josefina — known among those close to her as “Fina” — was quiet, elegant and ladylike, Franco French said, but nevertheless a trailblazer who oversaw the production of El Sol, one of the first Spanish-language newspapers in Phoenix, as well as several civic organizations and community efforts.

“I remember my mom telling me how [my grandmother] found out about some fieldworkers who were in freezing conditions,” Franco French said. “So she organized the community to go out and get clothes, and used the medium of journalism to get that message out.”

It was hard enough at that time being a woman, but being a minority woman and doing all that she did, Franco French said, was brave and noteworthy.

Her grandfather also wrote for El Sol and served as the publisher. Copies of the newspaper are very hard to find nowadays because not many people saved them, and libraries at the time didn’t subscribe to Spanish-language newspapers. The ones Franco French was able to donate will help researchers looking for firsthand accounts of Mexican-American life in Arizona during the 1930s through 1980s, when El Sol was in production.

“Times were really difficult in the 1930s for Mexicans,” Franco French said. “It was a very segregated community, and people fought very hard to end that. So for people who didn’t grow up with that, we need to know that others fought for us and paved the way, and we have to honor that.”

Together, her grandparents established and ran Phoenix’s first Fiestas Patrias celebrations, which her mother, Maria Josefina French, eventually took over. Among the items she donated are black-and-white photos of Fiestas Patrias “queens,” a tradition at the celebrations in Mexico that her parents brought to Phoenix, as well as a "china poblana"-style skirt, worn by dancers and revelers.

Franco French also donated her grandfather’s vast library collection, full of leather-bound Spanish-language literature and history books. He loved to read and write, and as she was going through his books, she found little pieces of poems he had written.

If her grandmother was a quiet trailblazer, Franco French’s mother was an audible force. When she took over the Fiestas Patrias duties from her parents, she took them very seriously. Franco French remembers one evening, around midnight, her mother went next door to their neighbor, then Secretary of State Richard Mahoney, and knocked on the door. She’d heard that he wouldn’t be attending the celebration and was adamant about changing his mind.

“She always made sure that the governor and the mayor [and other officials] had to be there. And if they weren’t going to be there, there had to be a really good reason, because it had to be inclusive,” Franco French said. “My mom was a fighter, and she was not afraid of anyone. She made sure that everyone knew we were Mexican and we were proud, and this was our history.”

Though Franco French did not take over the Fiestas Patrias duties from her mother, she still attends the celebrations today and echoes her family’s civic-minded nature through her work as the director of communications and community partnerships for Greater Phoenix Leadership.

There has been a lot of progress in recognizing the contributions of Mexican-Americans to the history of Arizona since her grandparents’ time, Franco French said — “but there’s always room for improvement.”

“We have certain politicians who have really focused on erroneous and negative aspects of being Latino,” she said. “[Individuals] who prey on a fear that isn’t true.

“I think it’s really important to share those stories. They make up who we are and what we become and remind us of where we come from. We all come from very humble roots, we’re all immigrants, so when we get some of this nativist fervor that certain politicians use for their gain, it’s good to look back and remember we all came from a certain place.”

Franco French is excited to see the items she has shared become available to the community, and she hopes they will serve to educate future generations.

“I am so thankful to ASU,” she said. “I would have just had it all in a box, and that’s not where it should be.”

Top photo: Children take part in a Fiestas Patrias parade in midcentury Phoenix, in a photo that is part of the French Franco family collection being donated to ASU.