Shows like “CSI,” “The First 48” and “Forensic Files” have captivated audiences, keying into a general fascination with murder, crime and forensics. In the world of make-believe, high-tech laboratories, fancy gadgets and instantaneous lab results solve a murder in 60 minutes (43 minutes with commercials).

But what really happens behind the scenes in a crime lab, and who are the real-world people who discover, examine and connect the clues left behind?

Kimberly Kobojek, program director of forensic science at Arizona State University’s New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at the West campus, worked for 17 years as a forensic scientist for the Phoenix Police Department before joining ASU as a clinical associate professor.

ASU’s forensic science program is more than savvy investigation. It emphasizes laboratory coursework in chemistry and biology, both essential to work in a crime lab. The program also features its own crime lab, where students begin to learn how to investigate scenes.

Video by Ken Fagan/ASU Now

To celebrate National Forensic Science Week, Sept. 17–23, the West campus is hosting Scott Rex from the Arizona Department of Public Safety’s Central Laboratory at “One Step Closer to CSI — Rapid DNA Analysis.” Rex will discuss the latest breakthroughs and answer questions about the technology and what it means for Arizonans at the free public lecture Tuesday evening.

Here, Kobojek delved into the world of forensic biology with the ASU Now team.

Question: What is forensic biology?

Answer: Forensic biology, in its “purest” definition is the application of biological sciences to matters of law. In other words, it's the analysis of evidence that may contain biological material that is collected from a crime scene. Forensic biology includes both serological tests [testing and ID of body fluids] and DNA analysis.

Q: Why is forensic biology an integral part of a potential or actual crime scene?

A: Like other pieces of physical evidence, forensic biology evidence can demonstrate a link between a person and a location or another person. It could be a link between victim and suspect, suspect and location, or victim and location, or all of the aforementioned (and possibly more). Some forensic biology evidence may be “invisible” or latent, so a person may not know it's there. Examples of this include “touch DNA,” or the DNA from skin cells that may be left when someone handles an object.

Q: What is the role of a crime-scene investigator?

A: It is the crime-scene investigator's responsibility to document, preserve and collect evidence at a crime scene while working in tandem with other law enforcement and (if necessary) medical-examiner personnel. This includes recognizing what may or may not be potential evidence.

Q: How is forensic biology applied in a criminal case?

A: Forensic biology can be applied in a few different ways. An analyst may test evidence for the presence of biological material and then conduct DNA analysis to obtain a DNA profile for that person/biological stain. If there is another person to whom that DNA sample may be compared, a comparison will happen.

For instance, if a suspect's shirt is found to contain a blood stain, the blood stain will be tested and a DNA profile is generated. The DNA profile will then be compared to both the suspect and the victim. If the victim’s DNA matches the bloodstain on the suspect’s shirt, we now have a link between the victim and the suspect. Statistics are then calculated to determine how unique that DNA profile is.

DNA analysis can also be conducted on samples from missing persons, unidentified remains and biological samples belonging to family members of missing persons.

Q: You mentioned DNA, and we know it is a significant tool in a criminal case. Is there value in extensive DNA collection and storage?

A: DNA can be an extremely useful tool in a criminal investigation and has helped “crack” many a cold case. However, as with any forensic science, its use needs to be tempered with common sense and the notion that just because you can do something doesn't mean you should do it. What I mean by this is that companies have advertised and collected a number of DNA samples from individuals all across America. I don't know how strict these companies’ rules are regarding allowing agencies such as law enforcement, immigration and insurance companies to access the DNA profile or the sample itself.

Crime labs who participate in the national DNA database, CODIS, have very strict rules about what can and cannot go into the database. There are also expungement procedures in cases of wrongful entry or wrongful conviction. And while crime labs typically keep the whole reference standards from individuals who submit them for testing in a criminal case, the samples aren't subject to transfer without at least an order from a law-enforcement official if not a court order.

I believe this technology is amazing, and it will keep getting even more sensitive, which means the DNA evidence must be collected, analyzed and interpreted with even more caution.

Q: One usually relates forensic biology to crime scenes and courtrooms. Does forensic biology exist outside the criminal justice field?

A: Yes, it does. DNA fingerprinting, first developed by Alec Jeffreys in the United Kingdom, was created in his university laboratory. It was only after the Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) technique was used in a criminal case that its use exploded outside of the academic environment.

Today, DNA/forensic biology is used by public and private crime labs, academic researchers, medical researchers and businesses who specialize in creating your ancestry profile.

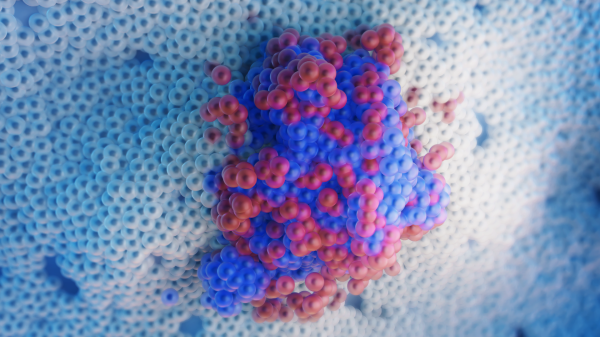

Answers have been edited for clarity and length. Top photo: ASU Clinical Associate Professor Kimberly Kobojek uses an ultraviolet light to fluoresce certain biological fluids in the forensics lab on the West campus. Kobojek’s lab focuses on reconstructing an incident through discovery and forensic science. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

More Science and technology

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would become one of the most famous fossil skeletons of our lifetime — the 3.2…

ASU and Deca Technologies selected to lead $100M SHIELD USA project to strengthen U.S. semiconductor packaging capabilities

The National Institute of Standards and Technology — part of the U.S. Department of Commerce — announced today that it plans to award as much as $100 million to Arizona State University and Deca…

From food crops to cancer clinics: Lessons in extermination resistance

Just as crop-devouring insects evolve to resist pesticides, cancer cells can increase their lethality by developing resistance to treatment. In fact, most deaths from cancer are caused by the…