ASU-led project to rebuild tribal housing with eye to future, rooted in tradition

Gila River Indian Community residents haven’t chosen their housing since the 1800s.

Their U.S. government-furnished homes are uninspired, inefficient and lacking reference to culture, experts say.

A community-led research project headed up by Arizona State University has the potential to turn it all around.

“Indigenous people have an interrupted history in North America,” said Wanda Dalla Costa, a visiting eminent scholar from Canada based in ASU’s School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built EnvironmentASU’s School of Sustainable Engineering and the Built Environment is part of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering..

“Boarding schools, the reservation system and the outlawing of cultural traditions segregated indigenous people from their practices and norms. Thankfully, Native American traditions are being reintroduced in a number of disciplines, including architecture and community planning. The best way forward is often through our traditions.”

Dalla Costa is referring to a new collaboration between ASU and the Gila River Indian Community, which started in 2015. That’s when Dalla Costa was introduced to Gov. Stephen Roe Lewis at an event celebrating the life and work of poet Sherman Alexie. When Lewis discovered he was talking to a Native American architect, his mind immediately went to work.

“The opportunity to work with an acknowledged design expert such as Professor Dalla Costa doesn’t come around very often,” Lewis said. “In partnering with ASU in developing sustainable housing would be the first of its kind for our community, bringing together modern technology and traditional building methods as the foundation of our future homes.”

Lewis, an ASU alumnus, wanted the university to explore the idea of building affordable, sustainable and energy-efficient homes with an eye toward the traditional adobe structures that once dotted their reservation, about 40 miles south of Phoenix.

Home building is at a healthy clip in the community. In the past two years, Gila River finished building approximately 475 single-family home structures, with plans to build an additional 600 in the next five years — and those 600 would incorporate designs from the project with Dalla Costa.

The partnership typifies one of ASU’s design aspirations by connecting with communities through mutually beneficial relationships, said Bryan Brayboy, ASU special adviser to the president and President’s Professor of indigenous education and justice.

“Wanda Dalla Costa is enacting ASU’s commitment to working with tribal communities in creating futures of their own making,” Brayboy said. “Her work, rooted in listening to the community’s needs, is innovative, insightful and imaginative. It is only the beginning of something very big.”

Dalla Costa said over thousands of years living in the Arizona climate, tribal members developed sophisticated methods of adapting to the hot and arid climate by building brick adobe homes, using shade structures for outdoor living, cooking outdoors to reduce heat gain in the home and, at times, living in subterranean dwellings.

“This is what climatic resiliency in architecture looks like, and principles such as this need to be reinvestigated here in Arizona,” said Dalla Costa, who is a member of the Saddle Lake First Nation of Northern Alberta.

According to Climate Central, Phoenix is experiencing 6.2 more days above 110 degrees since 1970, and the city’s nighttime temperatures have also increased almost 9 degrees since 2000 due to heat-island effect.

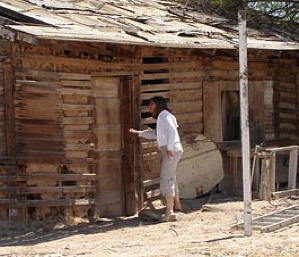

A typical adobe-style home in the Gila River Indian Community, Gila Crossing, circa 1900. Photo courtesy of USC Special Collections

The heat wasn’t a real problem for the original inhabitants of Gila River, who built homes that suited their lifestyles.

“The adobe’s thick walls protected the tribe members from the heat and were very effective,” Dalla Costa said. “When you live in this kind of climate, you figure out real fast what works.”

What hasn’t worked so well are the homes furnished by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, which was established in 1824 to oversee and carry out the federal government’s trade and treaty relations with indigenous tribes.

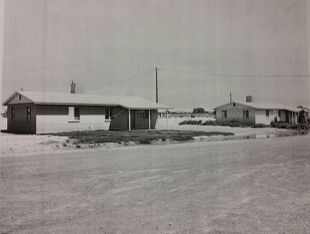

The first recorded adobe structure on Gila River dates back to the 1300s. The structure, known as the Casa Grande, is still standing. Adobe, along with sandwichMud packed with lumber forms and attached to a structural framework of posts. construction were the most common types of structures before the mid-1960s, when the Housing and Urban Development (HUD) started furnishing homes on the reservation. The HUD model was replicated across the USA, regardless of culture, climate or local materials and construction techniques.

Sandwich-style homes started popping up on the Gila River reservation in the 1920s. Photo courtesy of Kelley and Susan McGuinness/Defiance Photography

“It’s a one-size-fits-all approach to architecture,” Dalla Costa said. “The HUD home isn’t designed for this climate.”

That often translates to higher energy bills during the summer — some as high as $500 a month. For community members on fixed incomes, this can be a real hardship.

“A main goal is to contain utility costs with quality construction and energy-efficient methods,” Lewis said. “It’s not only important for our homes to reflect the past and the future, but as an end goal they must be energy-efficient.”

Buy-in from the community was also a must for Lewis, who wanted tribe members involved in the project from the start.

“It’s all about changing peoples’ perception that we’ll be creating something as beautiful and more efficient than they once had,” Dalla Costa said.

Dalla Costa and BriAnn Laban, a visiting doctoral student studying architecture from the University of Hawaii, met more than 100 residents in several community meetings and presentations to establish rapport and engage them as co-collaborators on the project.

HUD started building homes on the Gila River Reservation starting in the mid-1960s. Photo courtesy of Robert Nuss

“Most of them felt a disconnection to their homes,” said Laban, who is from the Hopi tribe in northern Arizona. “A lot of architects had come in before thinking they knew what the community needed, but having a Native American perspective was important to them.”

Dalla Costa’s team of architecture students is hoping to come up with a number of designs and begin a prototype home next year. The aim is to have a sample wall section ready in time for next May’s Mul-Chu-Tha fair and rodeo in Sacaton, Arizona.

“A fully built prototype home would enable community members to touch and see the inside, and experience how these homes would look in a contemporary setting,” Dalla Costa said. “Once they walk inside, they can make a decision if this type of home would be a good fit for their community.”

More Science and technology

Hack like you 'meme' it

What do pepperoni pizza, cat memes and an online dojo have in common?It turns out, these are all essential elements of a great cybersecurity hacking competition.And experts at Arizona State…

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive — under pressure.One such innovation is the newly released tomato variety…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper fish. Nearby, children chase bubbles and move to music, while…