Editor's note: This story is being highlighted in ASU Now's year in review. To read more top stories from 2017, click here.

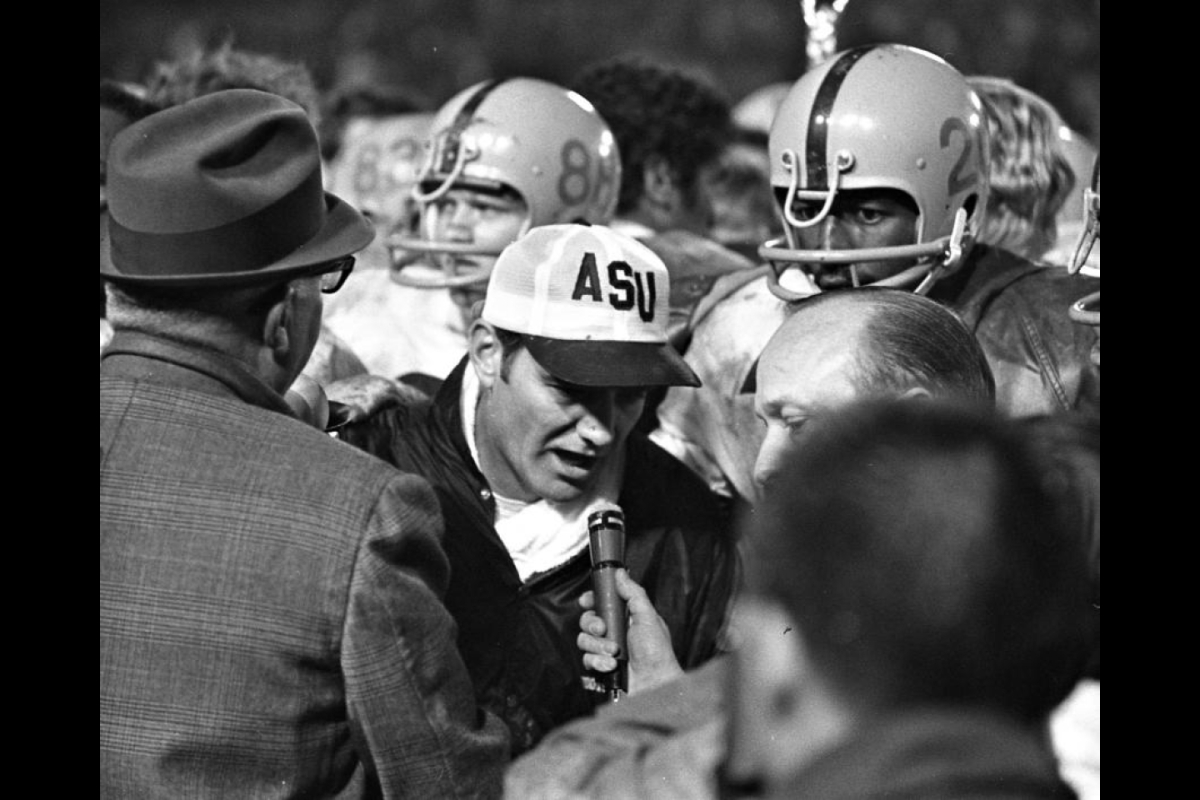

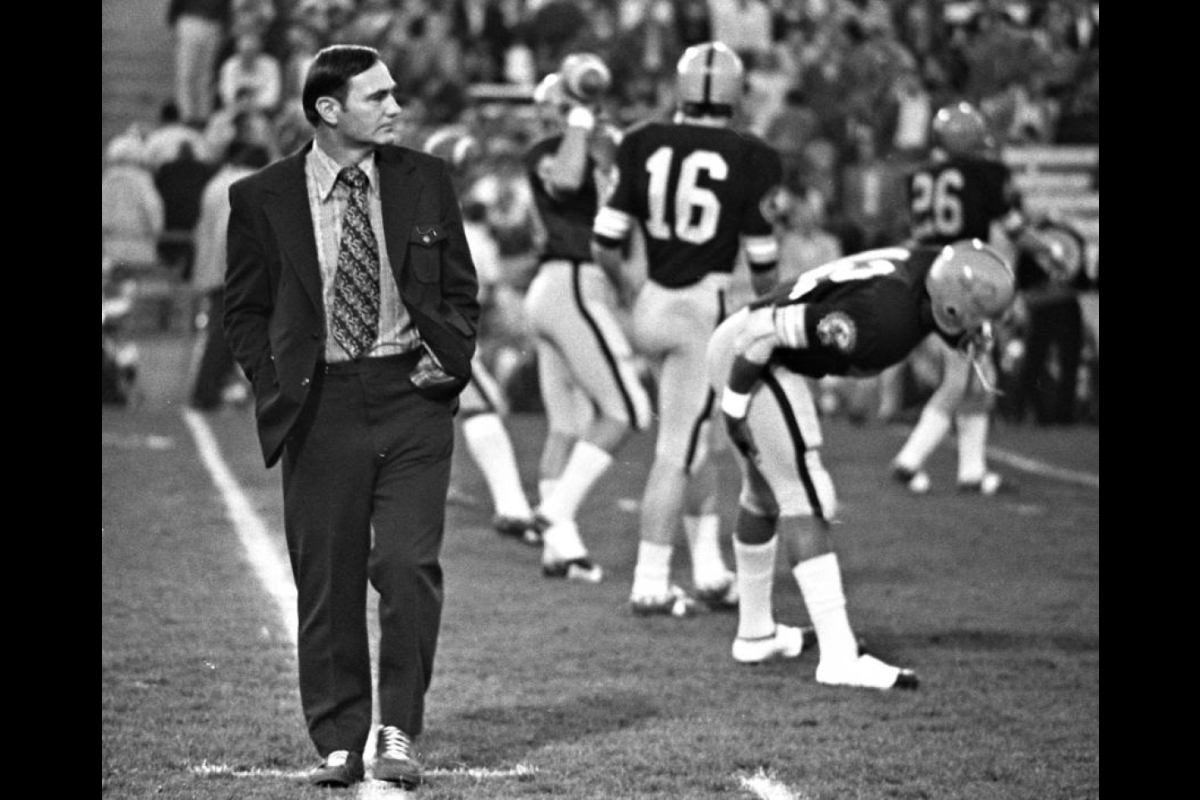

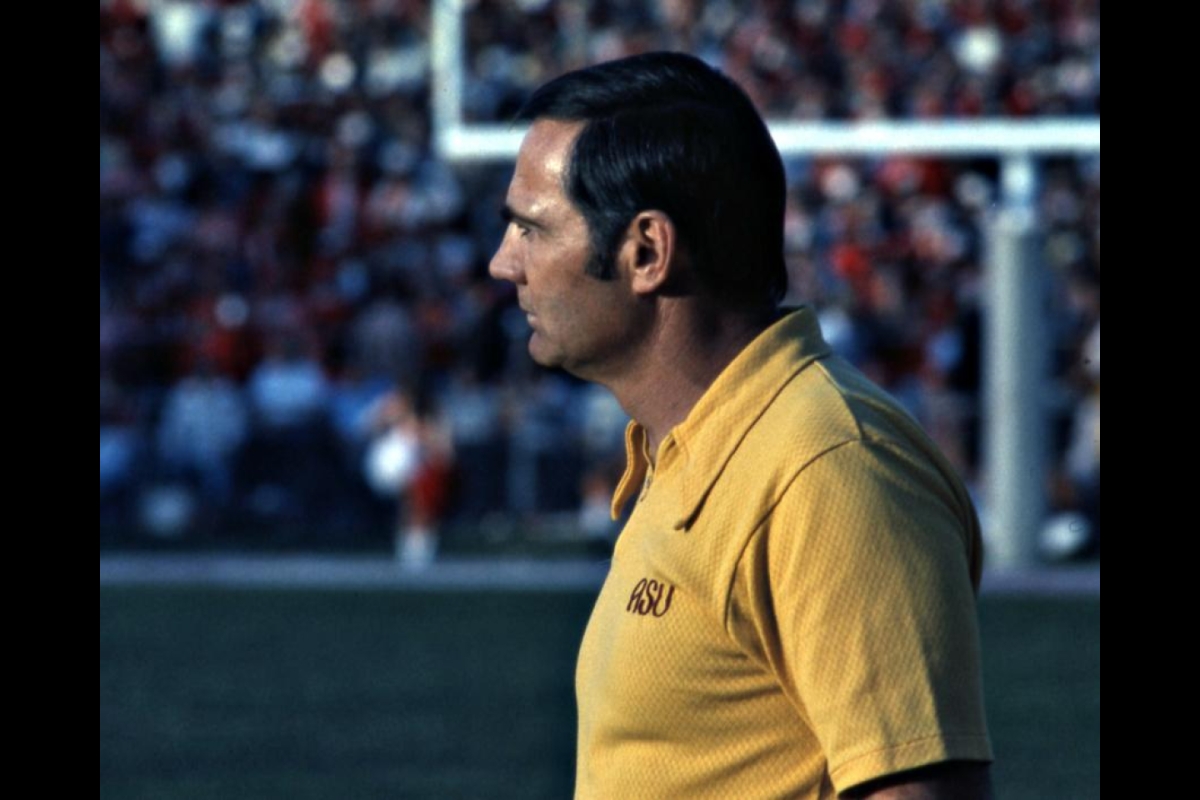

Frank Kush, Arizona State University and College Football Hall of Fame inductee and the winningest coach in Sun Devil football history, died Thursday at age 88. Kush was a part of the ASU family since 1955 and served in many roles over the years, most recently as an ambassador for Sun Devil Athletics.

Frank Kush

"Coach Kush built ASU into a national football power,” ASU President Michael M. Crow said. "He taught us how to make football work, and he put ASU on the map long before it was a full-scale university. Throughout his life he maintained his strong connection to ASU, working with coaches and devoting time to the football program. By growing ASU football he helped us build the whole university into what it is today. He will be sorely missed.”

Kush started his career at ASU in 1955 as an assistant under former head coach Dan Devine. Three seasons later, on Dec. 22, 1957, Kush became the 15th football coach in Arizona State history.

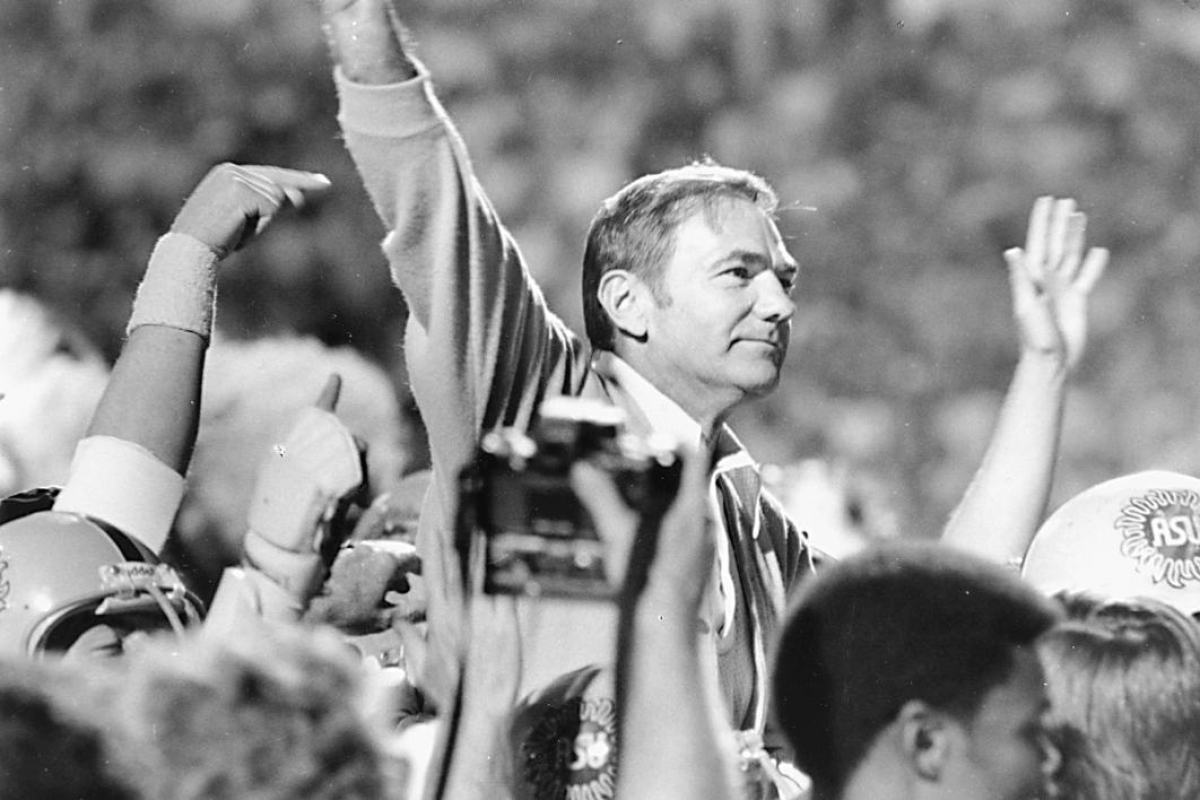

Kush went on to win 176 games — the most in school history — across 21.5 seasons and was elected into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1995. He led his team to seven Western Athletic Conference Championships and guided the Sun Devils to winning seasons in 19 of his 22 years. The Hall of Famer also holds the ASU football record for most postseason victories.

“Frank Kush is Sun Devil football,” said ASU Vice President for University Athletics Ray Anderson. “… Today, he and his family are in our hearts."

Read the full story about Kush and his impact on the university on the Sun Devil Athletics site here.

In the players' words

In October 2011, Kush and players from his 1958–1979 teams gathered at ASU for the Legends Luncheon. Watch the memories and hear what players had to say about their coach.

What's in a name?

In the late 1950s, efforts were afoot to change Arizona State College's name to Arizona State University. There were strong feelings on both sides.

Kush was among those who played a key role in drumming up support for the "university" change. Hear Kush and others speak about what it was like during that time.

More Sun Devil community

A champion's gift: Donation from former Sun Devil helps renovate softball stadium

Jackie Vasquez-Lapan can hear the words today as clearly as she did 17 years ago.In 2008, Vasquez-Lapan was an outfielder on Arizona State University’s national championship-winning softball team,…

Student-led business organization celebrates community, Indigenous heritage

ASU has seen significant growth in Native American student enrollment in recent years. And yet, Native American students make up less than 2% of the student population.A member of the Navajo Nation,…

Remembering ASU physical chemist Andrew Chizmeshya

Andrew Chizmeshya, a computational chemist and materials scientist whose work spanned over three decades at Arizona State University, died on March 7 at the age of 63.A dedicated mentor and cherished…