Far out in the asteroid belt, more than 200 million miles from Earth, an asteroid the size of a Volkswagen Beetle lazily orbited the sun. Then something — we’ll never know what — disturbed it.

It was knocked out of its orbit into an elliptical orbit. It swung closer and closer to the sun. Then, last summer on June 2, it roared into Earth’s atmosphere at 40,000 miles per hour.

This random chain of cosmic events landed it on the homeland of the White Mountain Apache Tribe in eastern Arizona.

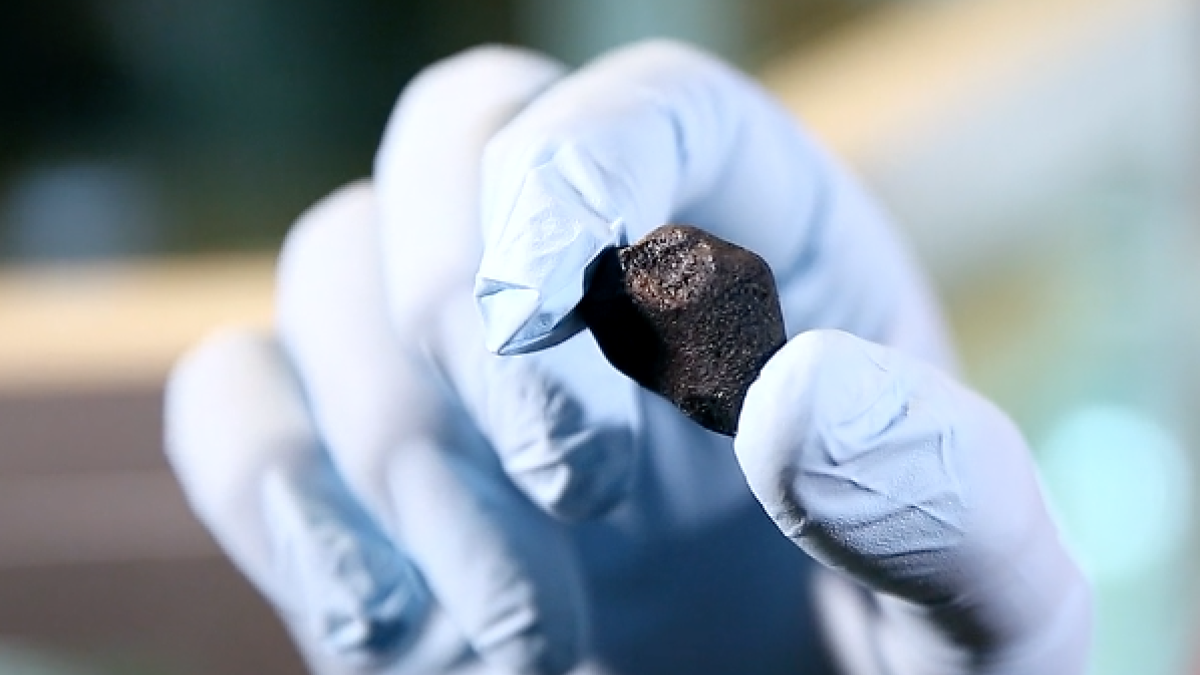

Now it has a name. The tribe has named their meteorite Dishchii’bikoh Ts’iłsǫǫsé Tsee. In English, it is CibecueThe town of Cibecue is close to where the meteorite was found. Star Rock. It was officially confirmed Monday.

Recovered by an Arizona State University team during a three-day expedition, it is a meteorite like no other ever studied.

“It does contain things we have not seen before,” said Laurence Garvie, research professor and curator of the Center for Meteorite Studies in the School of Earth and Space Exploration.

It is an ordinary chondrite — the most common type of meteor. However, when Garvie examined it in detail, he found some unusual features.

“Ooo, we’ve never seen anything like this before,” he said. “We just finished the initial scientific analysis of Dishchii’bikoh. It turned out to be really interesting. In one respect it’s an ordinary chondrite, but when we looked at the structure there’s aspects we’ve never seen before. This is where the future scientific analysis will take place.”

Video and top photo by Ken Fagan/ASU Now

It has been classified as an LL7 meteorite. Only 50 of that type have been found over the world. This is the first in North America.

“Look at the structure inside,” Garvie said. “These stones are really, really fragile. It’s like someone crushed this rock with a mortar and pestle and then squeezed it back together very gently. How did that structure form? That’s something we still need to work at.”

The name and classification were approved by the Committee for Meteorite Nomenclature, a 12-member international committee that classifies all new meteorites found around the world. The committee is part of the Meteoritical Society. They mull such questions as, is the name appropriate? How do you justify it being a certain type of meteorite? Is the science there? It’s a difficult and time-consuming process.

“It’s something the public knows almost nothing about,” Garvie said. “It’s a lot of work. It’s not just me eyeballing it saying, ‘It’s a whatever.’ It’s hours of work here and hours of work on microscopes and hours of work looking through boring Excel spreadsheets. Then you have to write a report and then you have to submit it to the nomenclature committee and then, assuming everything is OK, you have to publish your findings. So it’s a long, long process.”

The meteorite belongs to the White Mountain Apache Tribe, but it will be curated in perpetuity at the center on the university’s Tempe campus. Permission to curate the meteorite took months of legal work. Because the meteorite belongs to the tribe, they chose its name.

“We wanted something that reflected the local environment and what’s special about it,” Garvie said.

Jacob Moore, assistant vice president of tribal relations at Arizona State University, and tribal chairman Ronnie Lupe were key to securing permission from the tribe to search on their land.

“This would not have happened without a lot of people,” Garvie said. “It’s just been a really, really fun story.”

More Science and technology

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive — under pressure.One such innovation is the newly released tomato variety…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper fish. Nearby, children chase bubbles and move to music, while…

ASU water polo player defends the goal — and our data

Marie Rudasics is the last line of defense.Six players advance across the pool with a single objective in mind: making sure that yellow hydrogrip ball finds its way into the net. Rudasics, goalkeeper…