So you think Cinco de Mayo is a made-up holiday contrived to sell stereotypically Mexican bar food and alcohol to gringos? Turns out, you’re mostly right, according Arizona State University Professor Alexander Aviña.

Aviña, who teaches history in the university’s School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, says the holiday started to grow beyond the Mexican-American community in the Southwest in the late 1980s when Latino-focused advertisers saw an opportunity.

“Business people saw that the Mexican-American community in the US was gaining in consumption power, and the thing is once you do that you open it up for everybody and it becomes totally commercialized,” Aviña said.

To learn more about this holiday that has changed drastically in the last 30 years, ASU Now spoke with a pair of experts on Mexican-American history. Aviña, who teaches Mexican history, and Professor Monica De La Torre, who teaches media in the School of Transborder Studies, helped provide this list of things to know about Cinco de Mayo:

1. It’s not Mexican Independence Day.

Mexican Independence Day is in September and celebrates the nation's liberation from Spain in 1810.

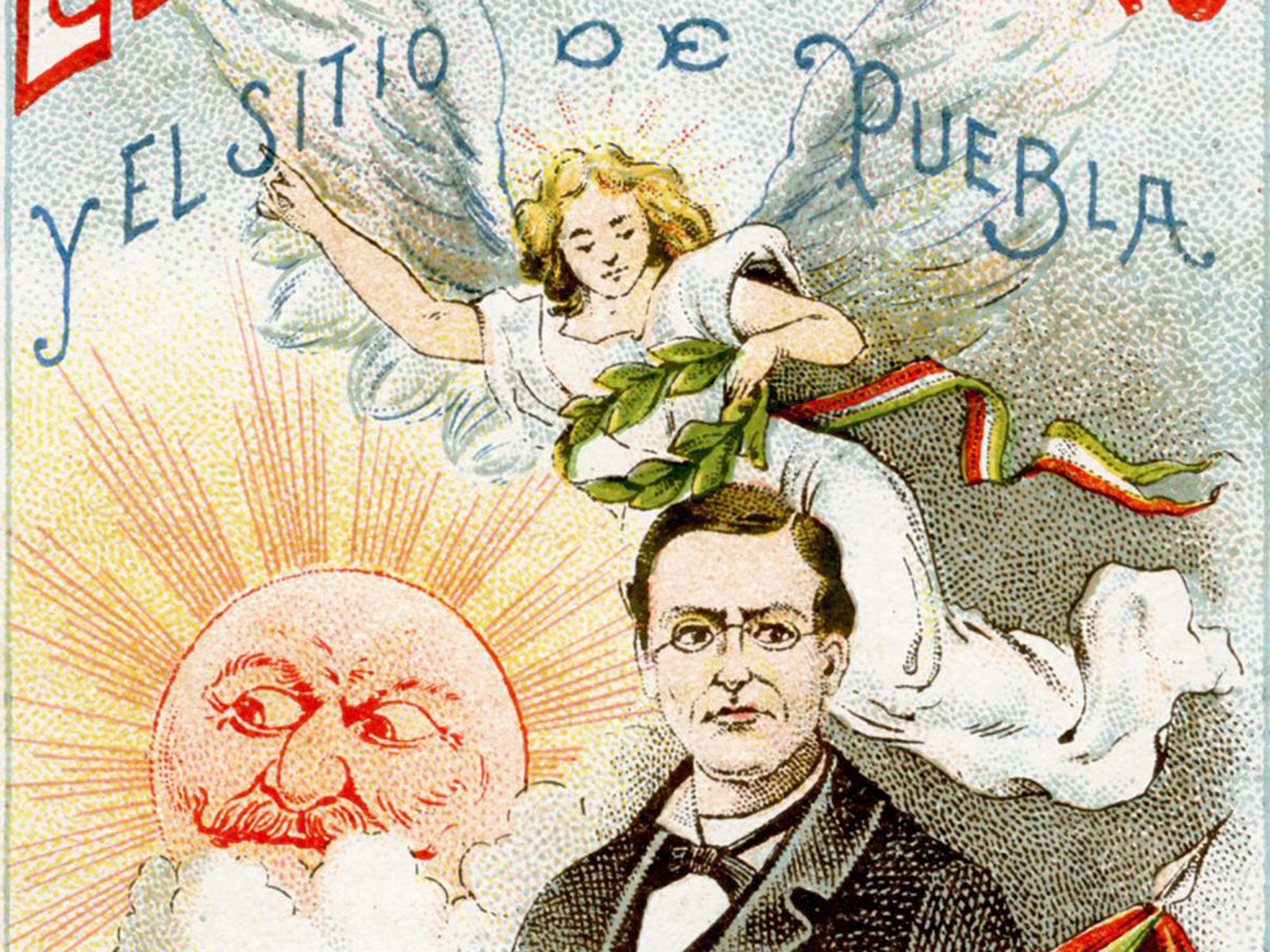

Cinco de Mayo recalls a skirmish more than 50 years later, the Battle of Puebla, when Mexico was fighting against a French invasion. A ragtag group of Mexican workers and farmers joined up with an outmatched army unit to take down one of the strongest military powers of the day — at least in one battle.

A French expeditionary force, Aviña said, was “defeated by a combination of underfunded, undertrained professional army and a bunch of irregular guerilla fighters who were peasants — and dressed like peasants — and had an assortment of bad, bad weaponry,” including machetes and slingshots.

The invaders, meanwhile, would have had muskets and cannons, and “they totally underestimated the tactical awareness of (Mexico’s Gen. Ignacio) Zaragoza and the fighting spirit of these Mexican fighters.”

2. The Battle of Puebla was just the start.

"The Execution of Emperor Maximilian" oil painting by Édouard Manet. Courtesy of the Yorck Project

That victory was the only success against the French, who proceeded to overtake Mexico and rule from 1862 to 1867, by installing the only European royal “crazy enough,” Aviña said, to take the job: Emperor Maximilian I.

As the U.S. Civil War was winding down, the U.S. government was able to turn its attention to the French and wanted them out of North America. Also, France’s standing in Europe was being jeopardized by a unifying Germany.

Napoleon Bonaparte decided to withdraw troops from Mexico. Maximilian, an Austrian loyal to France, however, chose to stay.

Maximilian “arrives in Mexico, he rules for a couple of years, he alienates everybody because he’s too liberal for the conservatives, and the Mexican liberals are in no way going to accept an emperor installed by a foreign force,” Aviña said.

Maximilian was executed in 1867, and the only traces remaining of the French occupation were the baguette used in torta sandwiches or the crepes used to prepare crepas de huitlacoche.

3. The battle is commemorated in Texas.

A portrait of Gen. Ignacio Zaragoza. Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress

Zaragoza was born in modern-day Texas, and his birthplace is commemorated in what today is Goliad State Park, where the U.S. government rebuilt his birth home.

The people of Puebla, Mexico, near Mexico City, the site of the famous battle, established a 10-foot bronze statue of Zaragoza in 1980.

Zaragoza’s second-in-command during the battle was no other than Profirio Díaz, who helped depose Maximilian and became the ruler of Mexico for the next 35 years.

He was so heavy-handed that he “causes the explosion of the Mexican revolution in 1910,” Aviña said, effectively setting up the government system that exists today.

4. It's been celebrated ever since — but not like this.

As early as 1865, Spanish-language newspapers in the U.S. West show committees being formed to raise funds and awareness against the French occupation. The communities from California to Texas these publications served had become American overnight with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, and this was their way of exerting influence on a nation with which they continued to identify.

“Cinco de Mayo during the 1860s as it's celebrated or commemorated in places like California really helped developed what historians refer to as a greater Mexican identity, so a Mexican identity that goes beyond borders,” Aviña said.

In the ’60s and ’70s, the Chicano Movement revived the holiday, Aviña said: “It’s part of recuperating parts of a Mexican past that will give some sort of national pride and dignity to people who have been oppressed racially and treated like second-class citizens in the U.S.”

5. It's been increasingly commercialized.

People gathered downtown recently to listen to Entre Mujeres, a trans-local music composition project between Chicanas/Latinas in the U.S. and Jarochas/Mexican female musicians in Mexico. Entre Mujeres project includesTylana Enomoto of Quetzal, among others. Photo by Tim Trumble/ASU.

As the holiday became commercialized in the ’80s and ’90s, the Mexican-American community largely ceased to identify with it, Aviña said.

Monetizing the one and only Mexican-American holiday means tacos, tequila and mariachi music — which is problematic, De La Torre said.

She sees the holiday as it’s celebrated today as a missed opportunity to actually connect.

“It’s an unjust stereotype to say that Mexican food is only beer, tequila, tacos and salsa. Instead of only listening to mariachi on Cinco de Mayo, you should listen to other bands. Chicano Batman is a great band; Quetzal is a great band.”

De La Torre suggests that it's OK to celebrate the holiday, but make sure you're learning more about it as you do.

Aviña, meanwhile, said, “I’m going to probably put posts on Facebook about offensive use of Mexican dress and costume.”

More Law, journalism and politics

Kate Spade brand co-founders stitch fashion legacy into Cronkite Alumni Hall of Fame

From Mary Tyler Moore dreams to runway success, iconic fashion designers Elyce Arons and the late Kate Spade are the newest members of the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication…

Trailblazing Spanish-language journalists remind students that choosing journalism is a privilege

Iconic Spanish-language journalists Jorge Ramos and María Elena Salinas accepted the 42nd Walter Cronkite Award for Excellence in Journalism on Tuesday, Feb. 24, during a luncheon at the Sheraton…

When police moonlight, who’s watching?

When police officers work off-duty security jobs, or “moonlight,” often in uniform and sometimes with full police powers, the lines between public service and private interest can blur.A new…