The wood-burning fireplace is now a reading nook and the once-bare walls are covered with bright posters, but the Child Development Lab at Arizona State University is much the same as when it started 75 years ago.

In the past eight decades, thousands of children have sat on the floor, tended the garden and played with blocks inside the walls of the Center for Family Studies, which houses the lab on the Tempe campus.

The Child Development Lab started — and remains — a place where the professionals directly interact with the kids, according to Robert Weigand, director of the school and senior lecturer in the T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics.

“That’s the idea behind the founding of lab schools — you can’t learn to work with kids without being with kids,” he said.

“You can’t learn how they think, how they behave or how your behavior will influence their behavior unless you’re with them.”

The lab serves three purposes: a full-day, early-childhood education experience for children; a research facility on children’s development; and a place for future professionals to train.

The lab is probably the oldest continuously operated early-childhood center in Arizona, said Weigand, who has been researching the history of the lab and found some old newspaper articles and photographs.

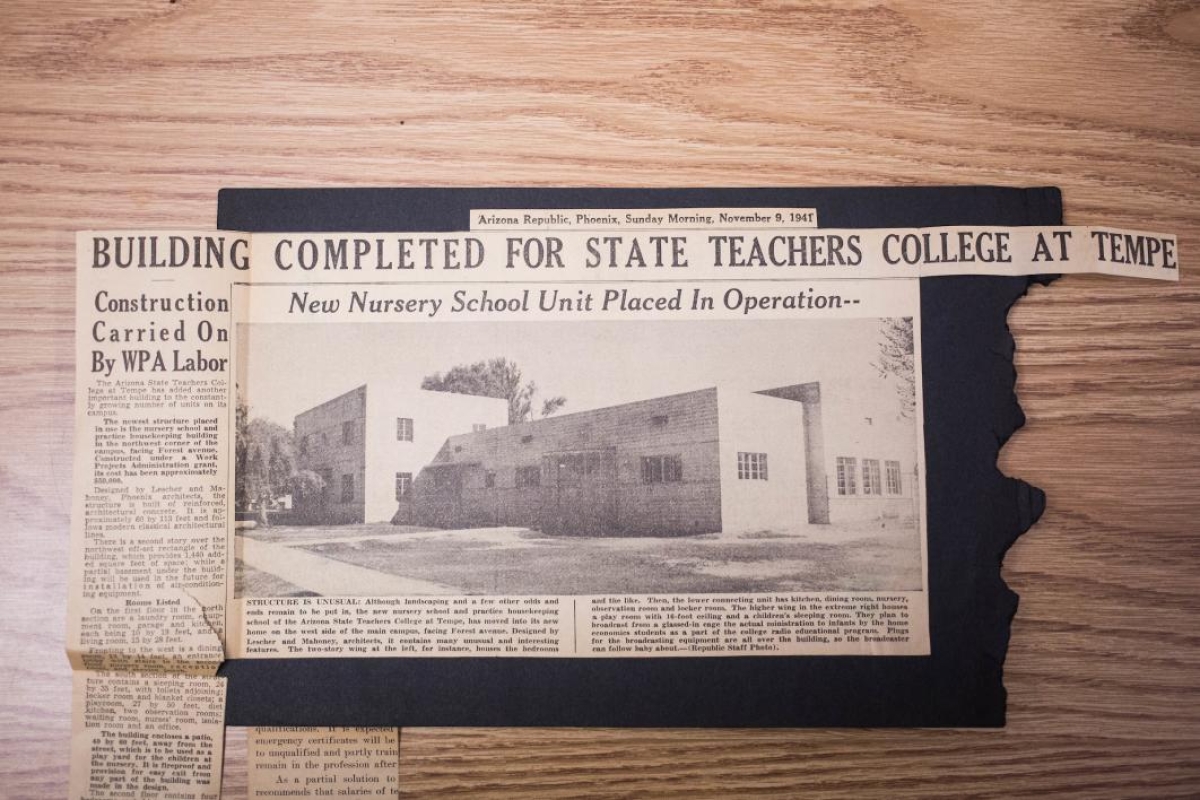

The building, completed with Works Projects AdministrationThe Works Projects Administration was a federal agency that employed millions of people on public works projects, including buildings and roads, from 1935 to 1943. money, was finished in 1942 and was called the Home Management House and Nursery School. The lower level was for the nursery school and the second level had bedrooms and a kitchen, where home economics majors lived for a semester while they learned to “keep house.” The second level now houses the Graduate Student Association.

Weigand isn’t sure exactly when, after the building was done, the nursery began accepting children, but he noted that the timing coincided with two movements — the influx of women into the workforce during World War II and the recognition at universities of early-childhood development as a worthy area of academic study.

“There was the ‘Rosie the Riveter’ child-care movement,” Weigand said. As women started taking over jobs from men who went off to war, leaders including Eleanor Roosevelt were concerned about “12-hour orphans,” when the children were left alone. So the Kaiser shipyards in Portland, Oregon, started one of the first child-care centers in the country, in 1943.

These first centers started recruiting experts in early childhood to develop appropriate programs, Weigand said.

“Simultaneously, early-childhood programs were developing at universities around the country. They started in the 1930s and were starting to blossom, and most of them were related to schools of home economics,” like the one at Arizona State Teachers College in 1942.

The building itself, though it has been updated with air-conditioning, security and other amenities, hasn’t changed much. The fireplace still has the original decorative tiles with scenes of animals and children, and each classroom still has an observation booth with one-way windows.

And research continues. When parents enroll, they know the lab is a research facility, but they must give permission for their children to participate in each experiment.

Many of the studiesThere are two child-development research facilities on the ASU campus: the Child Development Lab in the T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family Dynamics, which started in 1942 and is a full-time program; and the Child Study Lab, in the Department of Psychology, which was launched in 1972 and offers part-time classes for children age 15 months to 5 years. involve observing the children, but sometimes the kids are asked to perform tasks or answer questions. One cleverly designed study investigated collaboration. Two children had to cooperate in a task in order for both to access some candy, and if one wanted to have all the candy, neither would get it.

“There’s a lot of ingenious work going on,” Weigand said.

A center full of children also is the perfect place for future researchers and teachers to learn how to interact with kids.

“Some of the research assistants, when they begin their graduate studies, haven’t worked with kids before. If you’re a stranger and ask a kid to come out and play a game with you, how do you do that in a way that makes it more likely the kids will say yes?” Weigand said.

Child Development Lab coordinator Courtney Romley watches children as they get ready to juice lemons for lemonade. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

Getting up close with the kids is key, according to Courtney Romley, coordinator of the school.

“The thing we tell every adult who walks through the door is you’ve got to be sitting on the floor playing. You have to be at their level,” she said. “You can’t be an adult who is towering over them.”

The center, with about 50 children enrolled, has a waiting list, and spots are in high demand. The lab accepts children from 20 months old to pre-kindergarten, and the curriculum focuses on building social and emotional skills.

Because of the lab format, there is a low ratio of staff to students. Besides the full-time teachers, all of whom have master’s degrees, 25 college students work part-time in the center, as well as future teachers who are interns or on a practicum.

“This means our teachers aren’t constantly having to manage the classroom and can instead be a part of building those relationships with children, not only the adult-child relations but peer-to-peer relationships as well,” Romley said.

On a recent day, the children tended to the tomatoes and artichokes in the garden and squeezed lemons to make lemonade. Several student workers sat on the floor and patted backs during nap time. One of the aides, Ben Derdich, knew the drill well because he attended the lab as a 3-year-old.

“A few things are different now,” said Derdich, a sophomore majoring in tourism. “I remember where they do group time now there used to be cubbies where we could squeeze stress balls and have alone time.”

Derdich was walking on campus as a new freshman last year when Weigand recognized him and invited him to apply for a job. Now he helps during lunch and makes up games on the playground.

“When I walk in after classes, the stress is instantly gone. It’s not even like work — you get paid to play with kids,” he said.

Top photo: ASU student worker Sam Christus, a junior, plays with kids in the Child Development Lab, which was finished 75 years ago this spring. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU instructor’s debut novel becomes a bestseller on Amazon

Desiree Prieto Groft’s newly released novel "Girl, Unemployed" focuses on women and work — a subject close to Groft’s heart.“I have always been obsessed with women and jobs,” said Groft, a writing…

‘It all started at ASU’: Football player, theater alum makes the big screen

For filmmaker Ben Fritz, everything is about connection, relationships and overcoming expectations. “It’s about seeing people beyond how they see themselves,” he said. “When you create a space…

Lost languages mean lost cultures

By Alyssa Arns and Kristen LaRue-SandlerWhat if your language disappeared?Over the span of human existence, civilizations have come and gone. For many, the absence of written records means we know…