ASU researchers at forefront of emerging field: Biohistory

Thanks to an unlikely fusion of disciplines, it’s an interesting time to be dead — especially for the famous.

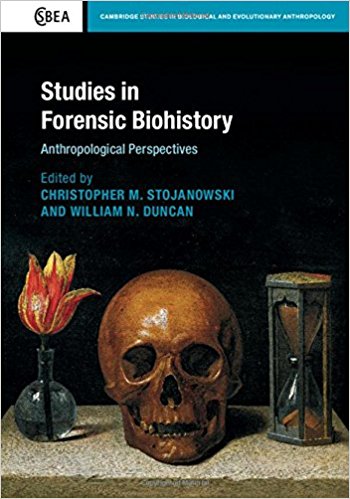

Today, researchers at the intersections of medicine, forensics, history, anthropology, folklore and pop culture are using science to confirm details about a range of historical figures, and ASU Professor Christopher Stojanowski has captured a collection of the most interesting stories in a new book, "Studies in Forensic Biohistory: Anthropological Perspectives."

It details cases that include the work of several ASU biohistory experts and covers Old West militias, Catholic martyrs and Shakespeare’s King Richard III.

“Oftentimes, it’s about trying to positively identify a body as belonging to a famous person from history, but there are also infamous historical events for which bodies can provide answers,” said Stojanowski, professor and associate director of undergraduate studies at ASU’s School of Human Evolution and Social Change.

“The public loves it all.”

The term “biohistory” was applied in forensic contexts by ASU Regents’ Professor Jane Buikstra and describes efforts to understand famous lives from biological remains.

The book, which Stojanowski co-edited with East Tennessee State University’s William Duncan, features several ASU experts describing notable cases.

As it turns out, studying the remains of potentially noteworthy humans is a complicated business. Biohistory shares much in practice with mainstream anthropology, which is often focused on giving voice to the voiceless. But while anthropology is like working in a vacuum, trying to hear anything at all, biohistory is like listening for a clear radio station amid endless, buzzing feedback.

There are always standing opinions and narratives in place in these cases, even if they rarely tell the whole story, Stojanowski said.

“This means people’s life stories and even broad sections of history can be vetted, revised or retold entirely based on what is found. As you get into these cases, it really begins to raise questions about the nature of fame and of personal attachments to things bigger than ourselves.”

On fame and the human brain

Stojanowski’s first biohistory case started more than decade ago when he and Duncan were contacted by a Franciscan friar, hoping they duo could confirm the identity of a skull. The Catholic church thought the skull belonged to a friar beheaded in 1597, who was being considered for sainthood.

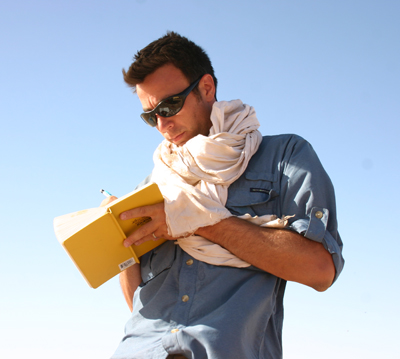

ASU Professor Christopher Stojanowski

After many scientific twists and turns (including a quickly abandoned idea of recreating fractures using a pig cadaver and recovering DNA from blood in the stomach of a louse recovered from the skull’s ear canal), the claim could neither be proved nor dismissed.

What stuck with Stojanowski, however, were the lingering implications of the effort — for science and living people alike.

“The friar in question was the subject of canonization procedures, so I was able to use a skill set for a community that specifically valued what I was trying to do for them,” he said.

Stojanowski realized his work had actually become a part of the friar’s story. He realized he was on the cusp of a new field of study.

“No one type of training prepares you to do this work, how to understand why we care and what the physical presence of fame and celebrity — in the form of the body — means to us,” he said. “The published literature is horribly scattered.”

In an effort to bridge this gap, Stojanowski and Duncan put out a call to others with this unique subset of experiences to share their most notable biohistory cases for the book.

“For 'Studies in Forensic Biohistory: Anthropological Perspectives,' we chose authors that could add something unique, theoretical or humanistic to the volume, more so than just an assessment of techniques and methods,” he said. “We also wanted to explore the range of individuals who become historically important, as there is some meaning to these patterns.”

Five paths to a notable demise

So what types of patterns has Stojanowski found exactly? Well, if you’re looking to be remembered, and studied, post-mortem for ages to come, this new volume can certainly provide some tips.

Option 1 — Die in a macabre way.

Stojanowski describes Margaret Clitherow, a Catholic martyr who was executed in a particularly brutal manner, as a prime example (squeamish be warned — Google at your own risk).

Option 2 — Make lots of friends, enemies or money.

“Famous leaders or scientific luminaries are often targeted for study, but ASU Associate Research Professor Richard Toon has a chapter in the book that does a great job exploring the behind-the-scenes motivations for why some biohistorical cases gain traction,” Stojanowski said. “Money is often there in the background somewhere.”

Option 3 — Be in the right place at the right time.

“In the U.S., the most visible biohistory cases involve Western outlaws and a series of catastrophes and massacres that occurred during Western expansion” Stojanowski said. “There is also a chapter on the Mountain Meadows Massacre, for example, as there is an entire specialty of sociology that studies death tourism — people visiting the sites of famous murders, mass disasters, etc.”

Option 4 — Leave something behind.

“In our book, there has to be a physical body or body part left behind or found that can be studied. That is our specialty,” Stojanowski said. “But there is a subset of work that seeks retrospective medical diagnoses, and here, journals and other written testimony can be used to try to diagnose (often with much controversy) a condition a famous person may have suffered.”

Option 5 — Have a reputation at home.

Stojanowski said he finds local folk heroes more interesting because their stories are less well known and documented, but they still helped shape the course of history. “If publishing an article on them brings awareness to conveniently overlooked aspects of U.S. or world history, then that to me is the greater service done by this type of work.”

Acknowledging the fringe, while moving into the mainstream

Even as the concept of biohistory develops and solidifies, it still bears some remnants of its relative youth, particularly in the hands of amateurs, the scientifically untrained or others who might be drawn to the sensational more than the substantive.

Stojanowski hopes this new volume can encourage more real conversation about the social theory, complexities and responsibilities involved in dabbling with posthumous identities and its possible repercussions in the minds of the living.

“What right do people have to dissect someone’s health history hundreds of years after they died? The short answer is that most researchers probably don’t think about this as much as they should and the ethical guidelines are murky.”

On the other hand, he said, the pendulum can swing both ways.

“The book also discusses,” Stojanowski said, “some of the reputational rehabilitation that may have been part of the Richard III story that emerged over the last few years.”