NASA satellites to aid ASU researchers in California drought study

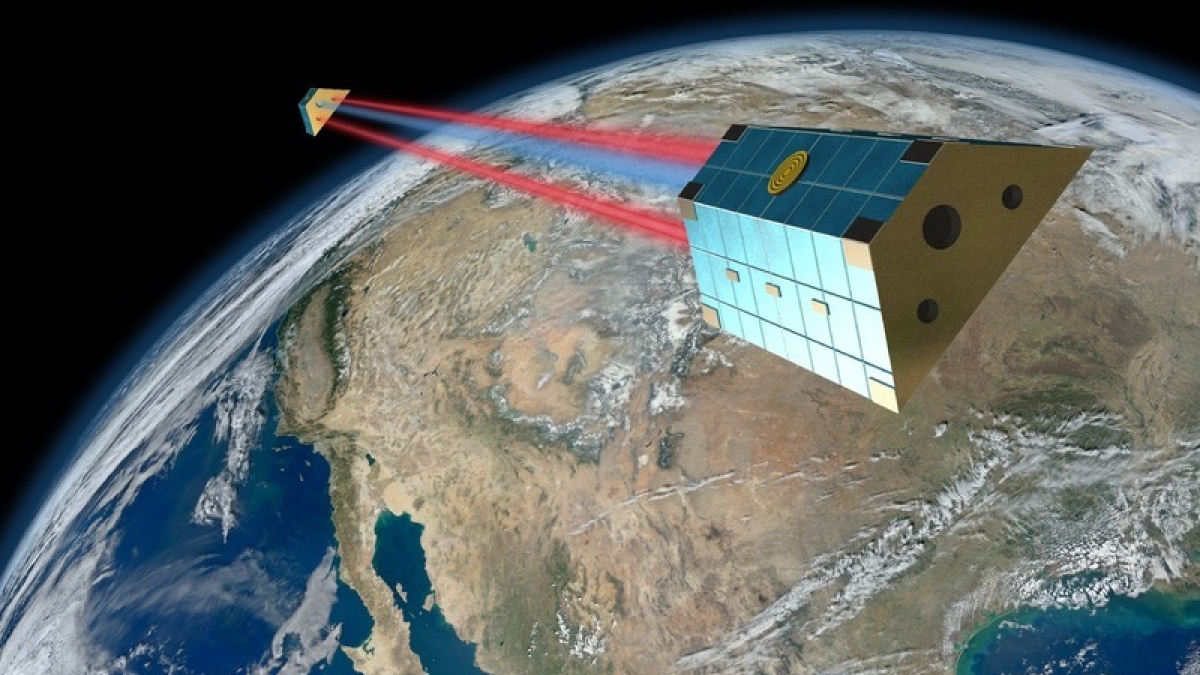

Artist rendition of the GRACE-FO satellites flying over North America. GFO satellite image credit: AEI/Daniel Schütze; background credit: NASA/NOAA/GSFC/SuomiNPP/VIIRS/Norman Kuring

Water management and drought forecasting traditionally meant physically measuring surface water or groundwater, but Arizona State University researchers are tackling the problem in a new way: from space.

“Ironically,” said principal investigator Susanna Werth, “we will be going several hundreds of kilometers away from Earth in order to see what is going on under the surface.”

Werth and Manoochehr Shirzaei of ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration (SESE), together with Yuning Fu of Bowling Green State University, have received a $550,000 grant from NASA’s Earth Surface and Interior focus area for a three-year study to use satellite data to more accurately measure water resources in California and predict future water availability.

ASU’s involvement represents the latest from a university that has become known for ventures into space.

In this case, ASU researchers will analyze data from a mission known as GRACE and other satellites, but the school also has high-profile connections with NASA that include Psyche, a first-time attempt to explore a metal asteroid; LunaH-Map, which aims to find water on the moon; and OSIRIS-Rex, which seeks to collect a sample from the asteroid Bennu and bring it back to Earth.

While past studies on water resources and drought have focused mainly on low-resolution surface or groundwater measurements, this new study will combine strengths of several Earth remote-sensing techniques, including satellite gravimetry and satellite radar interferometry, to help provide faster, more continuous, more consistent, higher-resolution and cheaper water-related surface and subsurface observations.

Gravimetry, which measures changes to the gravity field caused by water mass budget variations through the Earth’s hydrological cycle, will be provided by the twin-satellite mission Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE). The researchers also hope to collect data from GRACE-FO, which is expected to launch at the end of 2017.

Changes in the hydrological cycle also lead to height changes of the land surface, which can be measured using space-borne Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR), a method that uses radar images to generate maps of surface deformation using differences in the phase of waves returning to the satellite.

“This will be a huge leap forward in understanding the dynamics of water resources,” said Werth, who also holds a joint appointment with ASU’s School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning. “Our hopes are that it will enable authorities and decision makers to accurately manage water resources and plan for future water allocations.”

While California was chosen because of its severe drought and water management crisis, the team hopes to expand the study to the southwestern U.S., including Arizona.

“The whole region is affected by a long-term drought,” Werth said, “with differences in severity, climate conditions, groundwater geology and water management approaches.”

The results of this research will contribute significantly to ASU’s Future H2O program, which seeks to face the challenges of climate-change water insecurity through wiser design principles, new data and algorithms for better water governance and business outcomes, and scalable nature-inspired technologies.

NASA’s Earth Surface and Interior focus area (ESI) supports research and analysis of solid-Earth processes and properties from crust to core. ESI uses NASA’s unique capabilities and observational resources to better understand core, mantle and lithospheric structure and dynamics, and interactions between these processes and Earth’s fluid envelopes.

ESI studies provide the basic understanding and data products needed to inform the assessment, mitigation and forecasting of the natural hazards, including phenomena such as earthquakes, tsunamis, landslides and volcanic eruptions. They also use time-variable signals associated with other natural and human-caused disturbances to the Earth system, including those associated with the production and management of natural resources.

More Science and technology

What do a spacecraft, a skeleton and an asteroid have in common? This ASU professor

NASA’s Lucy spacecraft will probe an asteroid as it flys by it on Sunday — one with a connection to the mission name.The asteroid…

Hack like you 'meme' it

What do pepperoni pizza, cat memes and an online dojo have in common?It turns out, these are all essential elements of a great…

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive —…