ASU history professor leverages downtown Phoenix with art tours, cemetery prowls

ASU student Juan Carrola, a junior majoring in criminology and criminal justice at ASU's Downtown Phoenix campus, takes notes at the grave marker of Sadie Thoma at the Pioneer and Military Memorial Park as part of his history course in the College of Integrative Sciences and Arts. Photo by Kelley Karnes.

The energy of the city works like a magnet for many of the 11,000 students at Arizona State University's Downtown Phoenix campus.

It also appeals to historian Pamela Stewart, senior lecturer in the College of Integrative Sciences and Arts, who builds out-of-the-classroom opportunities into her courses each semester to get students to “do” history with art museum tours and cemetery prowls.

“I like to get students out to discover the richness of Phoenix historical and cultural venues and engage them in activities where they can learn how to apply the historian’s skill set,” Stewart said, “and besides, it’s fun.”

Fertile ground for discovery

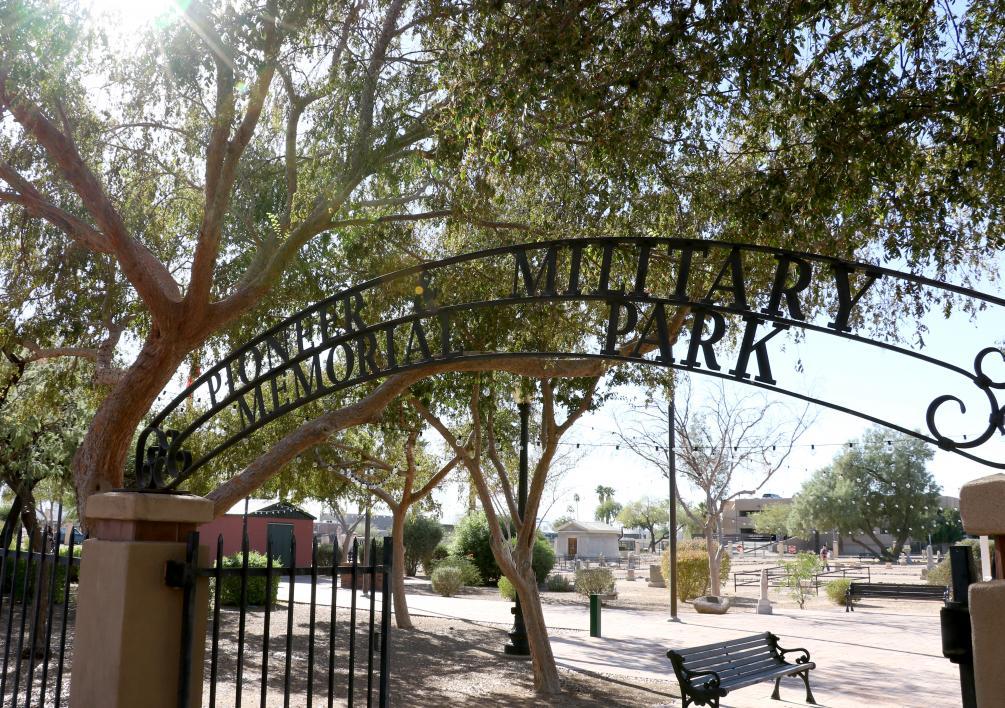

Less than 2 miles west of ASU’s Downtown Phoenix campus sits an 11-acre dirt cemetery that's become a history lab for Stewart’s courses.

The Pioneer and Military Memorial Park, which opened in 1988 and has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 2007, is made up of seven small cemeteries that were the burial place for nearly 4,000 people who died between 1884 and 1914.

More than 600 of the buried have grave markers of some kind, said Sterling Foster, the volunteer staffer at the park who was happy to field questions from the 83 ASU students who visited the park Thursday.

Buried there are children who died of scarlet fever, appendicitis and morphine poisoning. There are mule-train drivers and wagon makers, gravediggers and gamblers, soldiers, shopkeepers and saloon women. People who came to Phoenix from Sweden, Japan and France. Public servants, including former U.S. congressmen and territorial governors; the first surgeon general for the territory, thrown to his death by his horse; the first fish and game commissioner, whose gun exploded in his face just days after taking out $27,000 in insurance policies.

Further below the interred lie the ruins of a Hohokam village abandoned hundreds of years ago.

“Not being from here, I’d never seen this cemetery before,” said Belinda Caballero, who’s taking "Women in U.S. History" as a junior criminology and criminal justice major. “I like getting away from the books and the computer … and it’s cool to find things out that you can share with friends and family.”

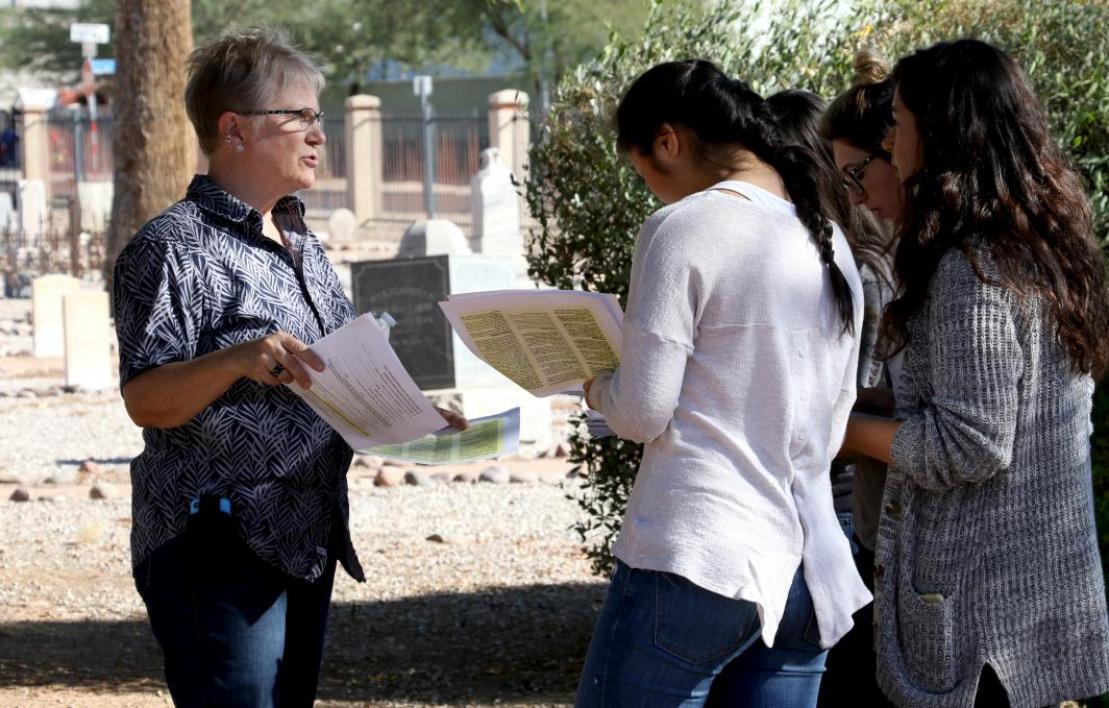

ASU College of Integrative Sciences and Arts history teacher Pamela Stewart talks with Cassandra Imperial, an undergraduate in the College of Health Solutions, and Imperial's father, Gilbert Ponce, as they explore the cemeteries in Pioneer and Military Memorial Park on Nov. 17. Photo by Kelley Karnes.

Freshman Cassandra Imperial, who is majoring in healthy lifestyle coaching, even brought her father, Gilbert Ponce, along for the tour.

“I’ve been wanting to visit it for a long time,” said Ponce, who has often driven by and tried to visit when the gates were locked (volunteers open the park on Thursdays and by appointment).

Imperial had just visited the gravesite of Leticia B. Rice, who, according to the research on the park’s website, also went by the names Tessie Murray and Mrs. Wright and was accidentally set ablaze in a saloon lodging house.

“None of that was mentioned on her gravestone,” Imperial said. “It was just her name and dates.”

Stewart challenged the students to explore and assess the grave markers as historical documents. She had them choose one individual from each of the six sections of the cemetery and compare the information on their grave markers with the information about the person, which volunteers and preservationists have made available in the park’s brochure and online site.

“I want students to think about and discuss what primary historical sources can tell us and what they can’t,” Stewart said. “Are there conspicuous absences on the marker or in the website descriptions? If you were to pursue additional information about this person, how would you learn more? These are skills they can apply to their own degree programs and personal interests.”

Learning to really look

In October, more than 100 of Stewart’s students from five different history courses signed up for 30-minute slots over two days to complete an assignment at the Phoenix Art Museum, which waived admission fees for the students.

In 14 small groups the students engaged in close observation of selected artwork with Stewart, who also volunteers at the museum as a docent.

“I reminded them that the exercise wasn’t about whether they liked art or wanted the artwork over their couch at home,” she noted. “This was about learning to observe closely.”

As students approached the art, Stewart asked them to discuss what drew their attention first. They added to their initial impressions as each group looked more carefully and longer. Then Stewart posed more questions, drew in historical knowledge, and then there was more looking and listening to what other students noticed, too.

In their written reflections about the experience, many students shared that this was the first time they’d ever visited an art museum, and they hadn't known what to expect. Several said they initially felt real apprehension.

Those same students used words like “amazing,” “awe” and “fascinating” to describe what they discovered and talked about wanting to come back on their own and introduce their families to the range of art they found, Stewart said.

“I loved this place and the peaceful way it made me feel,” wrote one student. “I was able to learn the difference between looking and truly observing with actual focus.”

More than 100 ASU students from five history courses at the Downtown Phoenix campus participated in an assignment at the Phoenix Art Museum in October. Photo by Pamela Stewart.

“When I arrived at the gallery, I just wanted to get it over with,” observed another student, “but ... Philip Curtis’s ‘Mountain Village’ made me think about my transition into college and how cluttered everything seems, but if I slow down then there can be that peaceful space, which can bring me back to sanity. I found it profound that I was able to reflect on my own life thanks to these paintings that someone else created.”

“For it being my first visit to an art museum, it was unexpectedly pleasant,” wrote a criminology and criminal justice major. “The art museum opened my mind a little bit more to curiosity. It’s good for the field I’m studying. ... The art museum really did change the way I felt about art.”

Reading the responses to the assignment, Stewart learned how much the opportunity affected her students.

“I must say, it was one of the best, most universally appreciated assignments I’ve ever had students do,” Stewart said. “Not only did they get it, but I learned a tremendous amount.”

She said she can’t say enough about the generosity of people in the arts and cultural community toward her students.

Stewart, for example, recently reached out to the Desert Botanical Garden about the possibility of students visiting an ASU-associated art exhibit there relevant to the course Immigration and Ethnicity in the U.S.

“The section meets late in the afternoon, after the garden buildings close, but that didn’t deter them from making it happen,” Stewart said. “They sent free VIP passes to the class to use any time in the coming year.”

More Arts, humanities and education

2 ASU professors, alumnus named 2025 Guggenheim Fellows

Two Arizona State University professors and a university alumnus have been named 2025 Guggenheim Fellows.Regents Professor Sir…

No argument: ASU-led project improves high school students' writing skills

Students in the freshman English class at Phoenix Trevor G. Browne High School often pop the question to teacher Rocio Rivas.No,…

ASU instructor’s debut novel becomes a bestseller on Amazon

Desiree Prieto Groft’s newly released novel "Girl, Unemployed" focuses on women and work — a subject close to Groft’s heart.“I…