Marketplace solutions work for many needs, but not all of them — particularly some of the most basic ones. That’s what Rimjhim Aggarwal found when she considered the question of how to guarantee affordable access to clean water to the people who need it.

Aggarwal, an associate professor in Arizona State University’s School of Sustainability, is an economist by training. She was taught that the laws of the marketplace would lead to efficient allocation and ensure that most goods we need would be available.

But she was left with a nagging question: How have the laws of the marketplace fared in terms of providing water for the millions of Indians living in abject poverty in slum communities in her home country? Many of these people do not have regular and affordable access to clean water or basic sanitation. Like brushing away remnants of a used pencil eraser, tidy economic models seemed to sweep poor populations from their evenly drawn curves.

“In fact, markets leave people thirsty,” said LaDawn Haglund, an associate professor of justice and social inquiry in ASU’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. “It’s only in the United States where we’re so wedded to the idea of markets as a solution to so many social problems.”

“When we talk about water for basic human physiological needs, the question of price raises not only economic but deeply ethical considerations,” said Aggarwal. “I think we need to ask ourselves: Do we want to live in a society where people don’t have the means to fulfill their basic needs?”

Haglund and Aggarwal do not want to live in such a society. Together they submitted a proposal to the National Science Foundation to explore the most effective pathways and mechanisms to translate the human right to water into practice.

One of these mechanisms is the use of courts. They proposed to document the way court systems have been used to advance the right to water in emerging economies with fairly well-developed legal systems, such as Brazil, South Africa and India.

The NSF responded that a comparison across three countries was too ambitious and asked the researchers to scale back the scope. But Haglund and Aggarwal were not deterred. They had seen numerous struggles of communities desperate for water in these countries — some successful and some unsuccessful — and were convinced that the comparison would be valuable, not only for these countries but also globally. They persisted in making their case to the NSF and ultimately were awarded $300,000 over three years for the full scope of their original proposal.

Over the past two years, Haglund, Aggarwal, doctoral student Julie Gwiszcz and undergraduate student Nicole Hale have traveled to Delhi, India; Johannesburg, South Africa; and Sao Paulo, Brazil, where issues such as pollution, affordable access to clean water and conflicting demands on water resources pose serious governance challenges.

Rimjhim Aggarwal (left) and LaDawn Haglund outside a community toilet in a slum in Delhi.

In each city they meticulously collected information on thousands of court cases related to water governance. They also met with stakeholders — judges, lawyers, government officials, utility managers and citizens — to understand the complex landscape of the right to water.

“We’re not just doing this as an academic exercise,” Aggarwal said. “We are trying to find ways where we can go back to the people we have interviewed and say, ‘This is how we think we can help you.’ ”

More than charity

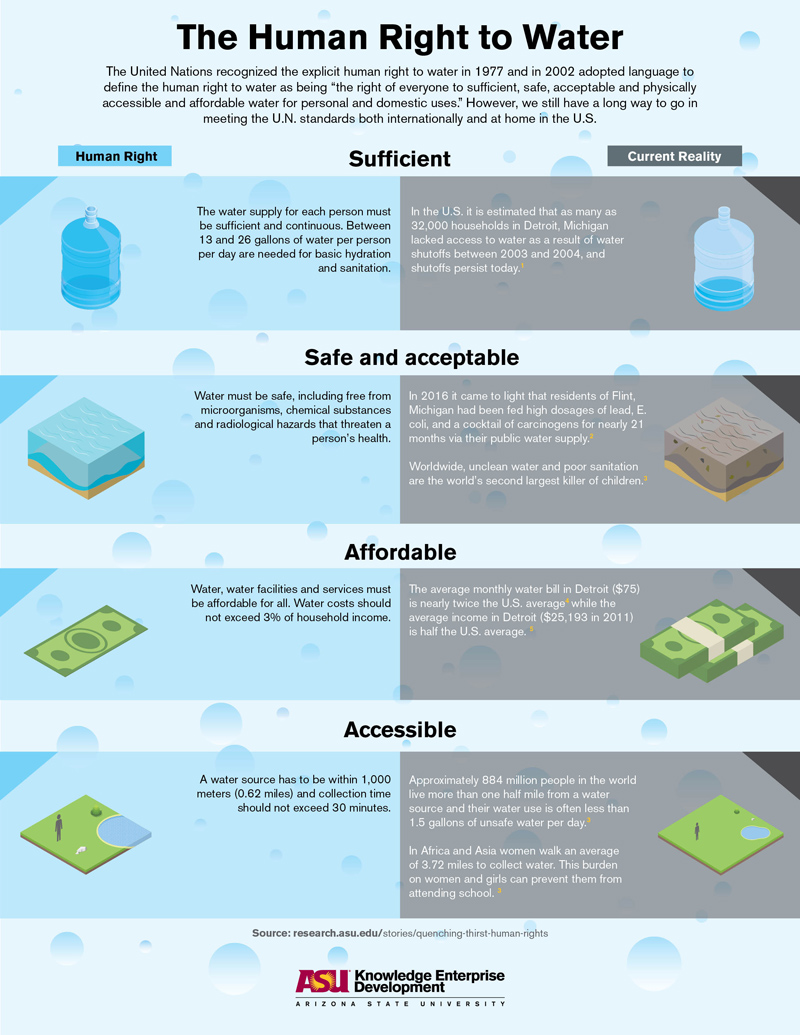

The United Nations has established a set of universal human rights to which each person is entitled. These include freedom from slavery, the right to have a family, the right to education and the right to water. Simply by virtue of being born, every baby is issued a theoretical bill of these basic human rights.

For many babies, these rights are effectively tucked into the swaddle and enshrine the bundle through adulthood. But for millions of babies — babies being born this very second — these rights are snapped away, either immediately or unexpectedly at a later date. This includes the right to water, which the United Nations defines as the provision of safe, clean, accessible and affordable drinking water and sanitation for all.

News photos of foreign aid workers distributing bottles of water in slums or building wells in rural villages in developing countries create the impression that providing water is an act of charity. Haglund and AggarwalHaglund and Aggarwal are leading an international, interdiscplinary workshop on their research titled, "Law and Urban Water Governance: Cross-Country Dialogues on Human Rights and Sustainability Challenges" this week at ASU. say their research was motivated by their frustration with the foreign-aid-driven model of top-down development. We should eschew the notion of charity, they say, and instead frame the provision of basic human necessities as rights.

This perspective offers profound philosophical and practical implications. People receiving charity are dependent on the moral sentiments of others. People with rights, even if they are poor and marginalized, can pursue legal action if a right is not fulfilled. A human right does not mean the government has to provide everything, says Haglund, but it does mean the government needs to create conditions in which people can access basic goods.

A violation of the basic human right to water has a profound impact on health, education and the ability to improve one’s circumstances. And women and children are often disproportionately affected by lack of access to water and sanitation.

In Africa and Asia, many women walk farther than the distance of a weekend 5K every day to collect water for basic survival. Young girls often are not sent to school so that they can walk to collect water. Close to half of all people in developing countries are suffering from health problems caused by poor water and sanitation. Together, unclean water and poor sanitation are the world’s second biggest killers of children.

The National Guard distributed bottled water in Flint, Michigan, in January 2016.

These problems are not limited to the developing world. People in the U.S. looked on in horror last year when utility companies cut off water indefinitely to thousands in Detroit, Michigan, who were unable to pay their water bills. And residents of Flint, Michigan, learned that their taps had delivered water contaminated with lead, E. coli and carcinogens for months.

Enforcing rights through courts

Courts can provide a space for citizens with few means to hold regulators, water companies and municipalities accountable for supplying clean water. Courts are a place where the duty to uphold a right can be enforced. By dissecting court cases and sharing what they find, Haglund and Aggarwal are shining light on the power that courts and human rights language can have in advancing the right to water.

“We're looking at how these courts are used to force people to respect, protect or fulfill human rights,” said Haglund.

The final product of the research will be a publicly available database of information. Although the court systems in each country are different, they can still be useful to people in other countries. Haglund and Aggarwal heard many eager requests to know what was happening elsewhere when they conducted interviews. In a sense, the database will serve as a GPS illuminating potential pathways toward water access and sanitation through complex court systems.

Governments tend to get the blame when citizens aren’t being cared for, and in some cases the blame is justified. But Aggarwal says that one of the enlightening aspects of the research was meeting officials with genuinely good intentions who shared the challenges of working in extremely complicated situations.

For example, in Delhi there are slum communities living in areas of the city that are not zoned for residences, either because they are unsafe or because they are near natural areas that could be damaged by human habitation. Government officials are reluctant to provide infrastructure for water to these areas because it would permanently establish the communities living there. In some cases, environmental-rights groups advocating for protection of fragile ecosystems are at odds with human-rights groups advocating for the right to water.

“This project made us very appreciative of the magnitude of the problem we face,” said Aggarwal.

An irregular settlement built on the protected Guarapiranga watershed, São Paulo, Brazil.

The case for water

The researchers were also surprised by the volume of court cases. Originally Aggarwal and Haglund expected to find perhaps a few hundred court cases documenting decisions related to water governance. They found thousands.

Cataloging the cases was tedious work, but the result will be a robust database with pragmatic strategies that can be applied in the real world.

“It’s less about us and more about the kind of world we want to live in. It’s destructive to the human spirit to deprive people of the very basics,” said Haglund.

Progress is made by inches but it is there, says Aggarwal. And there is evidence of governments in India, South Africa and Brazil taking systematic steps toward establishing universal access to water. Being part of a solution is exactly why Aggarwal and Haglund were determined to take on such ambitious research in the first place.

Aggarwal says that ASU actively facilitates the kind of cross-disciplinary research that allows an economist and a sociologist to study court cases happening on the opposite side of the globe.

“Here we stress making real-world impact and thinking about embeddedness, not only in your local community but in your global community, and developing integrated solutions based on multiple perspectives — not just the economic perspective,” said Aggarwal.

When their water was cut off, thousands of Detroit residents gathered in protest at the capitol building. They gripped signs and their voices rang out, proclaiming a value held by Americans, Indians, South Africans, Brazilians and people of every nationality around the world, but denied to many: “Water is a human right.”

For an in-depth look at water rights in the American Southwest, read ASU Now's three-part series.

Written by Kelsey Wharton, Office of Knowledge Enterprise Development

Top photo: Goats graze next to a polluted stream outside a township near Capetown, South Africa.

More Law, journalism and politics

Can elections results be counted quickly yet reliably?

Election results that are released as quickly as the public demands but are reliable enough to earn wide acceptance may not always be possible.At least that's what a bipartisan panel of elections…

Spring break trip to Hawaiʻi provides insight into Indigenous law

A group of Arizona State University law students spent a week in Hawaiʻi for spring break. And while they did take in some of the sites, sounds and tastes of the tropical destination, the trip…

LA journalists and officials gather to connect and salute fire coverage

Recognition of Los Angeles-area media coverage of the region’s January wildfires was the primary message as hundreds gathered at ASU California Center Broadway for an annual convening of journalists…