No internet, no power, no problem: ASU solar library empowers schools abroad

Many islands in the Pacific Ocean lack two things that are essential for accessing information and performing educational pursuits: a library and the internet.

Without this access, many teachers are without strong lesson plans or curriculum and community members lack books and multimedia.

But a new Arizona State University faculty member has figured out a way to deliver a digital library that doesn’t depend on existing internet connectivity — rather, it comes with its own Wi-Fi hotspot.

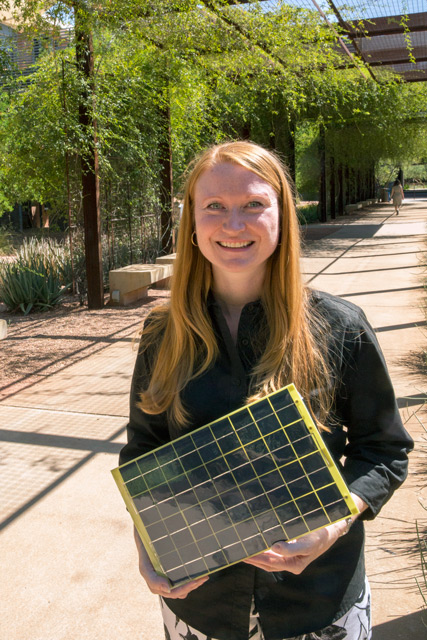

Laura Hosman

Laura Hosman is an assistant professor who began a joint appointment in ASU’s Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering and the School for the Future of Innovation in Society this semester.

Her innovative device, the Solar Powered Educational Learning Library, known as SolarSPELL, is a digital library full of educational resources that generates its own Wi-Fi signal and solar power. All that is needed to access the information is an internet-capable device, such as an iPad, laptop or smartphone. Basically, it’s a self-powered plug-and-play kit, portable enough to fit into a backpack.

The plastic case containing the technical components is waterproof and weatherproof, and it is covered with a compact solar panel.

The real genius of the device lies in its small, durable, credit-card-size computer — known as a Raspberry Pi — that is used as a server and delivers the educational content over its own Wi-Fi hotspot.

“The server is one directional, so the Wi-Fi doesn’t connect to the internet, but it serves up our offline library in the form of a website, so it looks and feels as though you’re online,” Hosman explained.

Curating localized content

On the SolarSPELL website are thousands of educational resources, including videos, ranging from math and English lessons to agricultural information to overviews of climate change.

Just like a community library, SolarSPELL can be a hub for people of all ages — from young children looking to watch instructional videos to community members looking to improve their agricultural practices.

SolarSPELL’s educational library is accessed using an internet-capable device, such as an iPad, laptop or smartphone. It operates like a self-powered plug-and-play kit. Photos by Pete Zrioka/ASU

In curating the content, Hosman insists on including as much localized information as possible. Currently, most educational content available to Pacific Islanders is provided by the governments of the U.S., Australia or New Zealand, and is not localized at all.

“When identifying content for SolarSPELL we try to think like a Pacific Islander, with a goal in the future of empowering locals to create their own unique content,” she said.

This means the device has a dual purpose of teaching things like science and geography, but also preserving and communicating local, traditional and indigenous knowledge. One example, preserved and accessible in the device, is a series of more than 70 Micronesian Seminar videos that cover 100 years of Pacific Islands history.

The importance of providing localized content came to Hosman several years ago during what she refers to as “a lightbulb moment.”

“I was showing a Micronesian Seminar video to a teacher and student, and their amazement at seeing the country’s president on the screen made me realize that these two had never actually seen a Micronesian — someone who looked like them — in a video before,” Hosman said. “It makes a huge difference if you can see yourself and your culture in the curriculum.”

Integration with Peace Corps

SolarSPELL has a strong working relationship with the U.S. Peace Corps in Vanuatu, Micronesia and Samoa. Peace Corps volunteers in the Pacific Islands are stationed at remote, rural schools for two years and have a mission to teach English and, where possible, technology in the schools.

“SolarSPELL provides a synergistic approach to the Peace Corps volunteers’ educational responsibilities, particularly when introducing technology into schools for the first time,” Hosman said.

She has learned that introducing technology in rural areas is successful only when the instructors are both technically proficient and embedded in the local community — a perfect fit for Peace Corps volunteers who know the local educational environment.

“It can take a long time to change the locals’ mind-sets and skill sets toward using technology. But Peace Corps volunteers are tech-savvy and are integrating SolarSPELL into schools in a successful way,” she said.

There are more than 100 SolarSPELL devices in the Pacific Islands, with 90 devices being managed by active Peace Corps volunteers.

A future at ASU and beyond

In January, Hosman will be taking SolarSPELL to Tonga for the first time. She is working with four engineering students in the Polytechnic School, one of the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering, on curating content specific to Tonga and creating hands-on lesson plans for teaching about solar power.

With the help of ASU students, Hosman said SolarSPELL will continue to evolve and improve — from enhancing the library’s website features to identifying more cost-effective assembly methods and components to potentially coordinating a SolarSPELL build day on location in the Pacific Islands with teachers or high school students.

Hosman said the project seems to “exponentially expand” with student interest and enthusiasm.

“What’s exciting is I don’t know what direction it will take next because ASU has an unlimited outlook and mentality,” Hosman said.

Long term, she hopes to see the device’s use expanded to all islands with Peace Corps volunteers, and then beyond.

“With time and dedication from ASU students, it could go across Africa and Asia,” she said.

Lofty aims like expanding SolarSPELL’s reach around the globe is what attracted Hosman to ASU.

“Teaching innovative concepts at a school that’s No. 1 in innovation in the country is the dream,” Hosman said.

She was attracted to the Polytechnic School for its project-based classes, especially with engineering students.

“At many schools, engineers learn a lot of theory, but don’t get their hands busy … yet being able to tackle hands-on projects is a main reason why many of these students became engineering majors,” she explained.

Hosman has taken previous students to Haiti, Micronesia and Vanuatu. She said bringing students into the field to see their work take fruition is a life-changing experience that alters their trajectory.

“ASU supports social justice, inclusivity, hands-on teaching and multidisciplinary learning. It’s a perfect fit because that’s what I’m all about.”

Laura Hosman is working with engineering students in the Polytechnic School to introduce the device to Tonga in January 2017. From left: James Larson, electrical engineering junior; Laura Hosman, assistant professor; Bruce Baikie, engineering mentor and implementation manager/lead; Tyrine Jamella Pangan, software engineering junior; and Miles Mabey, robotics engineering junior. Photo by Pete Zrioka/ASU

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU professor's project helps students learn complex topics

One of Arizona State University’s top professors is using her signature research project to improve how college students learn science, technology, engineering, math and medicine.Micki Chi, who is a…

Award-winning playwright shares her scriptwriting process with ASU students

Actions speak louder than words. That’s why award-winning playwright Y York is workshopping her latest play, "Becoming Awesome," with actors at Arizona State University this week. “I want…

Exceeding great expectations in downtown Mesa

Anyone visiting downtown Mesa over the past couple of years has a lot to rave about: The bevy of restaurants, unique local shops, entertainment venues and inviting spaces that beg for attention from…