Update: Nearly a year after it fell to Earth, the meteorite has an official name — one that ties it to the community where it was found. Read about it here.

On June 2, a chunk of rock the size of a Volkswagen Beetle hurtled into the atmosphere over the desert Southwest at 40,000 miles per hour and broke apart over the White Mountains of eastern Arizona.

A week later, one of Arizona State University’s top meteorite experts was off on a team expedition in the Arizona wilderness on an Apache homeland, braving bug bites, bears and mountainous terrain.

After three nights and 132 hours of searching, they were successful.

“This is a really big deal,” said Laurence Garvie, research professor and curator of the Center for Meteorite Studies in the School of Earth and Space Exploration at ASU. “It was a once-in-a-generation experience.”

It began when Garvie woke up on June 2, checked social media and saw that dozens of people and cameras witnessed a dramatic meteor fall in the wee hours of the morning. He immediately knew it was going to be a long day.

National Weather Service Doppler radar in Flagstaff swept the area and turned up three strong radar returns on White Mountain Apache tribal land.

“This thing exploded in the atmosphere,” Garvie said. “When the stone breaks up, things just start dropping. ... By simple physics we can estimate where these things are on the ground.”

The ASU team was granted permission by the White Mountain Apache Tribe to go onto their land to search for the meteorites.

Photo courtesy of Laurence Garvie

A lot of meteorite hunters immediately knew where it had fallen, but tribal lands are closed to the public, unless hiking or fishing with a permit. “People were excited, but it wasn’t on public land,” Garvie said.

A day or so after the fall, after Garvie had stopped being bombarded for interview requests from the press, he and Jacob Moore, assistant vice president of tribal relations at ASU, contacted the tribal council of the White Mountain Apache Tribe.

“(Moore) was absolutely pivotal to this,” Garvie said.

With tribal permission granted, the Arizona State University–White Mountain Apache Tribe Meteorite Expedition, as Garvie dubbed it, took off for the mountains. Tribal chief ranger Chadwick Amos and Game and Fish director Josh Parker met the team nearby to help them with their search.

Garvie, two grad students from the Center for Meteorite Studies and three professional meteorite hunters invited by the center took off in three high-clearance four-wheel-drive trucks. They brought food and water for a week in case they got stuck.

Like most backcountry roads in Arizona, it was a hairy two-track.

“We drove 5 miles an hour,” Garvie said. They blew a tire (their last spare) at one point. “We drove a mile an hour after that,” he added. “We took 1.5 hours to travel the 7-mile dirt road to our first campsite.”

Everyone was bitten by either cactus or insects. Bears wandered through camp one night. On the way out, they rescued two lost hikers. Because the mountains are tinder dry, they couldn’t have campfires, so they ate canned chili, nuts and jerky. One guy put Reddi-Wip on everything. “It was a real adventure,” Garvie said.

The terrain is beautiful, but rugged. You might want to hike to a point 1,000 yards away, but it involves traversing twice that to get there.

After three nights camping and 132 hours of searching, the team found 15 meteorites, ranging in size from a medium-sized strawberry to a pea. “These are pristine things that were in space a few days ago,” Garvie said.

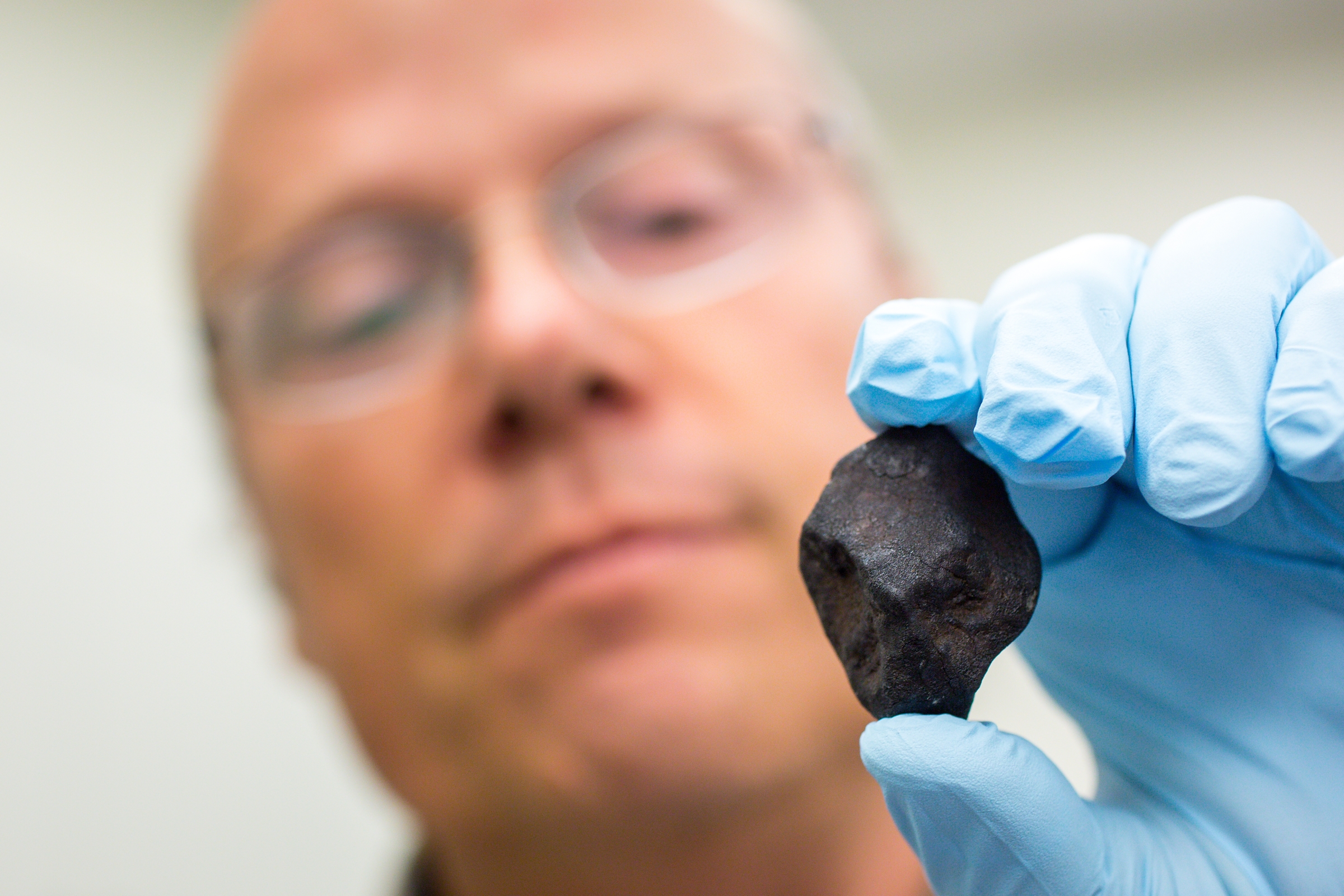

Laurence Garvie, curator of ASU’s Center for Meteorite Studies, on Tuesday displays the meteorite he found on his recent trek into the White Mountain Apache tribal area. His team found 15 meteorites from the June 2 fireball that broke up over Arizona. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

Searching consisted of walking slowly and scanning small patches of bare ground where it would be possible to see a small, black, rounded rock, according to Garvie.

Graduate students from the Center for Meteorite Studies, Prajkta Mane and Daniel Dunlap, both found meteorites.

Dunlap found one the size of a pea in a clump of grass. “Oh man, I can’t believe this is happening,” Dunlap said he thought when he saw it. “Oh my God, is that one? It is!”

“It was an amazing feeling,” he said later.

Mane also found her first meteorite.

“It was crazy,” she said. “You study these things in the lab, but to go into the field with experienced people and find one was really amazing.”

It was the third recovered meteorite fall this year in the United States. The other two were in Mount Blanco, Texas, and Osceola, Florida. All three finds were enhanced by Doppler radar. Without the Doppler data, the White Mountain finds would likely not have been recovered, Garvie said.

“Like all discoveries, something of this magnitude bridges the gap of earth science,” said Ronnie Lupe, chairman of the White Mountain Apache Tribe. “They say meteorites crashing down upon the Earth's surface is relatively common; however, to have them land on tribal lands is significant in discovery.”

The three citizen scientists — Robert Ward, Ruben Garcia and Mike Miller, all well-known to the center — discovered meteorites and handed them off to the collection. It was a condition of their joining the expedition, and they gladly accepted, attracted by the thrill of the hunt.

“I really want to stress how important they were,” Garvie said.

It was the second time Garvie has personally found a meteorite. He didn’t expect to find anything on the expedition. “I was hoping,” he said.

Finding a meteorite can be hard, but not impossible, Garvie said. “If you just went out to the western deserts of Arizona and looked really hard, you might find one every few days,” he said.

The meteorites the team found are ordinary chondrites. Chondrites are stony — non-metallic — meteorites that have not been modified from melting or differentiation of the parent body. It was only the fourth recorded fall in Arizona history.

“Every new meteorite adds a piece to the puzzle of where we came from,” Garvie said. “We need to stress how grateful we are to the White Mountain Apache Tribal Chairman Ronnie Lupe for giving us access. This area is normally totally off limits to non-tribal members.”

The meteorites will remain the property of the tribe; the ASU center will curate them. Moore said the university was honored to work cooperatively with the tribe on such a rare scientific discovery.

“They have extended tremendous cooperation in the work the ASU scientists are doing on the White Mountain Apache tribal lands,” said Moore.

Lupe thanked everyone involved for being mindful of tribal lands and their laws and ordinances.

“The findings of these meteorites belong to the White Mountain Apache Tribe as it was found on tribal lands; whatever is found is ours,” he said. “Tribal resource advisers play a major role in assisting this team as they proceed on tribal lands; they will have a major role in guidance of our traditional and cultural values as these values are one with the land.”

Meenakshi Wadhwa, director of the Center for Meteorite Studies and a professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration, said she was proud that the cooperation between everyone involved yielded such an amazing find.

“A fresh meteorite fall is always a fantastic opportunity to learn something new about the origin of our solar system and planets,” Wadhwa said. “I am really proud of the great teamwork between our ASU personnel, the meteorite collectors and members of the White Mountain Apache Tribe that made it possible to collect pieces of this meteorite for the benefit of science.”

Top photo: ASU graduate students Daniel Dunlap and Prajkta Mane consult their notes while looking for meteorites in the White Mountain Apache tribal lands. Photo courtesy of Laurence Garvie

More Science and technology

Hack like you 'meme' it

What do pepperoni pizza, cat memes and an online dojo have in common?It turns out, these are all essential elements of a great cybersecurity hacking competition.And experts at Arizona State…

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive — under pressure.One such innovation is the newly released tomato variety…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper fish. Nearby, children chase bubbles and move to music, while…