Pakistani engineering students battle energy crisis, gender roles

Master’s students Warda Mushtaq (second from the right) and Syeda Mehwish (on the right) spent the spring semester at Arizona State University with a cohort of Pakistani students as part of the U.S.-Pakistan Centers for Advanced Studies in Energy (USPCAS-E) program. In addition to advancing a research agenda in renewable energy, they toured Arizona sites such as the Grand Canyon. Photo courtesy of Hassan Zulfiqar

Two Pakistani women have important insights into their country’s colossal energy crisis.

Engineers Warda Mushtaq and Syeda Mehwish are master’s students that came to Arizona State University as part of the U.S.-Pakistan Centers for Advanced Studies in Energy (USPCAS-E) program.

Supportive parents, a hunger for scientific knowledge and progressive academic programs have fueled their successes in engineering, a field dominated by men in Pakistan and most parts of the world.

Their cohort, composed of 25 Pakistani engineering students, spent the spring semester learning new research techniques and tackling energy-related projects alongside ASU researchers.

Funded with an $18 million investment from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), USPCAS-E is a partnership between ASU and two leading Pakistani universities, the National University of Science and Technology (NUST) in Islamabad and the University of Engineering and Technology (UET) in Peshawar.

Renewables key to solving Pakistan’s energy crisis

Many engineers remember the device or question that first ignited their passion for finding scientific and technological solutions. For Mehwish, her interest began with a fascination concerning how televisions and radios worked.

Raised in southwestern Punjab, Pakistan, Mehwish said, “my earliest and fondest memories of childhood involved the wonders I could see and hear through these devices.”

For Mushtaq, her interest in engineering came later. Though born in Pakistan, she spent her childhood and teenage years in Saudi Arabia until she returned to her home country to pursue an undergraduate degree.

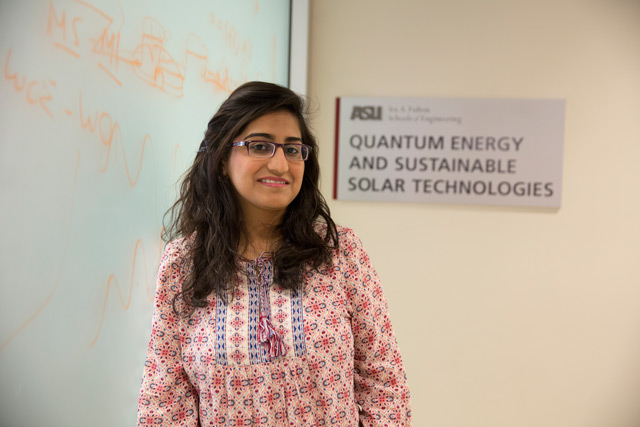

Warda Mushtaq conducted research in assistant professor Zachary Holman’s lab on advanced generation photovoltaics. Her research aspires to help solve the energy crisis in Pakistan with increasingly affordable solar power alternatives to fossil fuels. Photo by: Nick Narducci/ASU

“I have seen how posh the lifestyle of many communities in the Middle East is, compared to our lifestyle here in Pakistan,” she said.

She feels that the energy crisis facing Pakistan, in particular, is causing a majority of the societal and economic strain in Pakistan.

This energy crisis is deeply concerning, as the supply of energy is far less than the growing demand of the heat-wave prone country.

Due to management difficulties, increased power generation costs and underdeveloped infrastructure, power shortfalls approached 50 percent of national demand and the country experienced two major blackouts last year.

Reports also attributed more than 1,200 deaths last year to lethal heat waves, exasperated by rampant power outages.

An over-reliance on imported fossil fuels and untapped renewable energy sources have greatly contributed to the national crisis.

“I feel very passionate about using my skills to do something for my community, to contribute to resolving the energy crisis,” said Mushtaq.

At ASU, Mushtaq worked in assistant professor Zachary Holman’s lab on advanced generation photovoltaics. Her research aspires to help solve Pakistan’s energy crisis with increasingly affordable solar power alternatives to fossil fuels.

Solar power is one of the most feasible energy solutions in Pakistan, believes Mushtaq, “but it’s very expensive because all solar cells are imported.”

“My research is focused on the fabrication of low-cost photovoltaics…available to everyone in Pakistan, from our largest city to the smallest villages,” said Mushtaq.

Mehwish worked with associate research professor Govindasamy Tamizhmani in the Photovoltaic Reliability Lab on ASU’s Polytechnic campus.

“I am looking at making electricity cheaper for rural [communities] by proving the feasibility of standalone power plants in remote locations,” said Mehwish.

These alternative energy power plants could improve access and sustainability in rural communities in Pakistan, and across the world, if their feasibility can be proved.

The research contributions of engineers like Warda and Syeda aim to address this complex problem and are championed by leaders at their university.

“We believe that women can play an integral role in the socio-economic development of Pakistan and in resolving the energy crisis,” said Sonia Emaan, the communications and outreach specialist for USPCAS-E at NUST, the university Mehwish and Mushtaq attend.

“I believe that our women are giving their utmost in finding ways to perform with perfection … [including] working at the power plants, in the process industry, conducting field surveys, developing ways of improving existing processes at the oil and gas refineries, or designing and testing machinery for converting, transmitting and supplying useful energy to meet Pakistan’s needs for electricity,” added Emaan.

Time at ASU boosts research potential

Both Mehwish and Mushtaq decided to pursue a master’s degree in energy systems engineering at NUST, in part, because of the USPCAS-E program.

Syeda Mehwish spent the semester

working with associate research

professor Govindasamy Tamizhmani

in the Photovoltaic Reliability Lab

on the ASU Polytechnic campus.

She hopes to pursue a doctoral

degree next.

Photo courtesy: Syeda Mehwish

Mehwish enjoyed collaborating on her research at ASU, which she calls “a melting pot for people from all regions of the world.”

Warda describes her initial introduction to ASU as surprising.

“I think we were all a little shocked at how huge ASU is and just how much research goes on here,” she said.

Mushtaq says the USPCAS-E program jumpstarted her research career and has been “an amazing experience.”

She was so committed and excited about the opportunity USPCAS-E provided that she turned down a prestigious Fulbright doctoral program fellowship, offered by the United States Educational Foundation in Pakistan, to spend the semester at ASU.

In addition to funding from USAID, Mehwish won the British Council’s Scholarship for Women in Energy in 2013.

Both Mushtaq and Mehwish have returned to Pakistan to continue their careers in advancing renewable energy.

“I’ve always thought the focus of research should be on how something is going to affect your community, what the real-world application is,” says Mushtaq. “I see a lot of that kind of purpose-driven research here [at ASU], and that’s something I look forward to applying back home.”

Both students aim to pursue a doctoral degree.

Navigating a male-dominated society

On track to graduate this summer, Mushtaq and Mehwish are among four female students in their class of about 30 master’s students at NUST.

“But that ratio is increasing,” said Mushtaq, and NUST is focused on bringing more women into technological fields through recruitment efforts and the addition of specific facilities for female students, including living accommodations, a medical center, a gym and increased transportation offerings.

Total female enrollment at NUST is currently 30 percent, but the environmental science and engineering programs are approaching almost 50 percent.

“By being the backbone of the society and having a dominant representation in the population of Pakistan, [women] can provide a ripple effect with their understanding of engineering programs and the dissemination of their learning and practical application to the larger part of the community,” said Emaan.

Though many supportive teachers and parents encouraged Warda and Syeda on their engineering journeys, they acknowledge that many women face pressures that can limit career progression.

According to Mehwish, “society norms in Pakistan usually dictate that women and girls are expected to run a household instead of going after a dream job.”

“It was only through the constant support and belief of my family that I have reached where I am today,” she said.

At various times throughout her academic journey, Warda says she has encountered “inappropriate attitudes and comments” due to the unfortunate belief that women shouldn’t pursue careers.

“When I excel and do better than most of my male colleagues, I gain respect and observe a change in attitudes. This has given me confidence that the only way we can gain respect in this male-dominated society is by pursuing our dreams and excelling in them,” said Mushtaq.

“Society will not always be your best friend, especially as a woman, so you must be firm in your beliefs and stay true to your passion,” said Mehwish.

While championing the “sanctity and piousness” of her own culture, Mehwish admits it can be a struggle when she feels judged for her desires to interact with people from different religions, cultures and parts of the world.

Despite any criticism, Mehwish champions becoming a “global citizen.”

“Only when we understand and listen to the problems faced by people from all corners, can we completely eradicate the petty things dividing us, the simple things distracting us and the radical things holding us,” she said.

Mushtaq added, “I look up to every career-minded woman who is determined to be strong, independent and brave enough to not worry about what the society thinks she should or shouldn’t do. From a Pakistani women who drives an auto to support her family to the Pakistani scientist in the team who discovered gravitational waves, and everyone in between, all these women — their strength inspires me.”

Mehwish said her time at ASU helped her to gain confidence in her research focus and gave her the zeal to “bring Pakistan to the forefront of academic research, especially for young girls who aspire to be researchers and scientists.”

More Science and technology

Cosmic clues: Metal-poor regions unveil potential method for galaxy growth

For decades, astronomers have analyzed data from space and ground telescopes to learn more about galaxies in the universe.…

Indigenous geneticists build unprecedented research community at ASU

When Krystal Tsosie (Diné) was an undergraduate at Arizona State University, there were no Indigenous faculty she could look to…

Pioneering professor of cultural evolution pens essays for leading academic journals

When Robert Boyd wrote his 1985 book “Culture and the Evolutionary Process,” cultural evolution was not considered a true…