'Vehicle of Resistance'

Kenny Dyer-Redner is somewhere in the wilds of Nevada’s Indian country, and he’s spinning his wheels.

No, he’s not taking a break from his studies at Arizona State University. Dyer-Redner is on a two-wheeled mission.

The American Indian StudiesThe American Indian Studies Program is an academic unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. student is speaking about indigenous history as part of his master’s thesis and touring 15 Indian reservations in 34 days on a bike. He’s hoping to inspire youth and other community members to make their own history.

“As American Indian people, we are taught to think about history from a Western point of view. Too often American Indians accept this,” said Dyer-Redner, who is about three-quarters finished with his 34-day bike ride, which will encompass approximately 1,000 miles in and around northern Nevada.

“Most people think that stories and storytelling are powerful. I argue that stories have the power to shape our thoughts, consciousness and even our actions. I urge people to begin a process of engaging in physical activity and intellectual reflection.”

Dyer-Redner’s thesis, “Vehicle of Resistance: A Bicycle Ride for the Land, Culture and Community,” uses a theoretical framework that explores four concepts: history/land, storytelling, the physical body and political action.

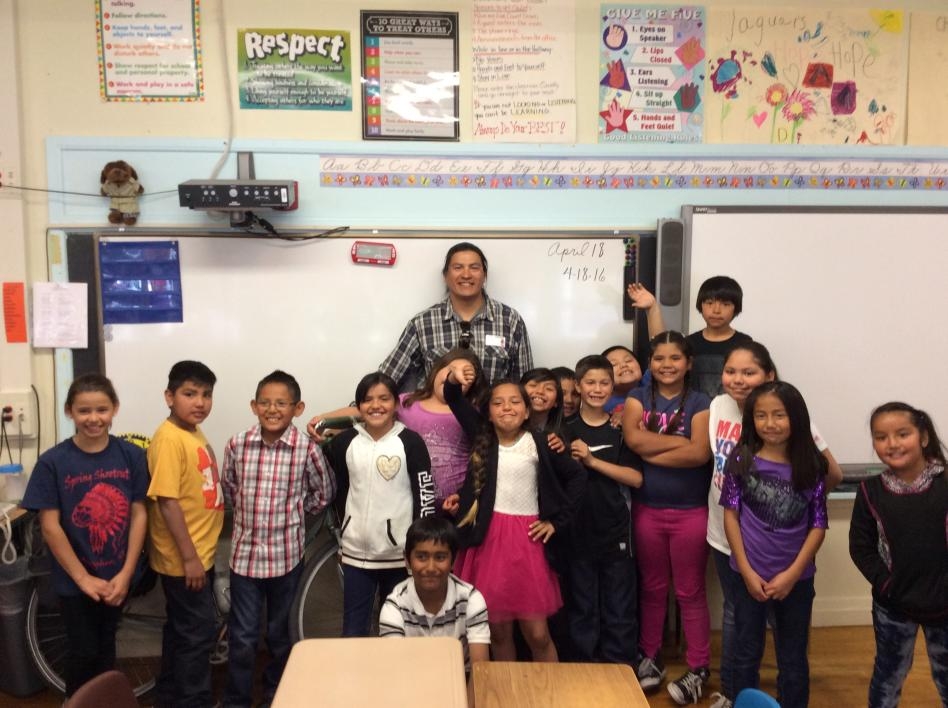

Kenny Dyer-Redner visits students on the reservations he's biking through.

Photo courtesy of Dyer-Redner

He’s putting to the test a theory he called “Active Indigenous Presence,” which argues that a presence of indigenous thought, voice and physical body disrupts and introduces the concept of decolonization and self-determination.

“At one time this country was all indigenous land, and right now we’re all separated on different reservations,” Dyer-Redner said. “We might be scattered, but there’s indigenous people everywhere and they’re very supportive. They are showing me that we are all one big community.”

Those kinds of life lessons are inspiring and the epitome of use-inspired research, said Bryan McKinley Jones Brayboy, director of the Center for Indian Education and ASU’s Special Advisor to the President on American Indian Affairs.

“Kenny’s thesis project is remarkable in that he is, quite literally, embodying his scholarship. I suspect he will learn a great deal about himself as he braves the elements and tells his story,” Brayboy said. “Young boys and girls in communities will see that Native peoples can be thoughtful and serious scholars, generous people and engaged community members.”

The 34-year-old master’s student is fully engaged at the moment; he rides his bike 50-70 miles a day and sleeps in a tent at night. He said it helps him to connect with the land and the people.

“I purposely chose a bike because it’s not as quick as a vehicle and it forces me to get to know the landscape more intimately,” said Dyer-Redner. “There’s no way I’d be able to do that driving by in a car really fast.”

Riding a bike at 4,000-feet elevation can have its drawbacks, said Dyer-Redner. He has endured rain, severe wind, snow, and on a couple of occasions, hail. But that’s nothing compared with the sacrifices he made before taking off for Nevada earlier this month. He quit his job as a stocker at the Amazon Fulfillment Center in west Phoenix and had to get the blessing of his wife and two kids, ages 15 and 2, to fulfill his thesis.

But Dyer-Redner is quickly acquiring a new support system while on the road, thanks to a social-media post by longtime pal Derek Hinkey, who announced Dyer-Redner’s academic sojourn. News of his arrival has caught on with the locals, as well as an Elko, Nevada, TV station, who recently filed a story.

“When I come to a reservation, people either have heard of me or know I’m coming,” said Dyer-Redner. “I’ve even had people pull me over on the side of the road and say, ‘Hey, you’re that guy!’ People feed me, have hosted me in their homes and are showing they care.”

In return, Dyer-Redner speaks to youth groups, high school and college students, community members and elders about his life on the Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Indian Reservation. He speaks honestly about some of the obstacles he faced in his youth — racism, loneliness and some self-destructive behavior when he turned 12. He said athleticsDyer-Redner played football and basketball and was recruited by several colleges. He was a champion boxer on the club level at the University of Nevada, Reno. gave him the discipline to turn his life around and that education is helping to shape his future.

“Everybody can relate to my story because growing up I was very shy and passive, your typical res kid,” Dyer-Redner said. “I was a good athlete, and that gave me the confidence I needed to overcome my shyness. But some of these kids are dealing with challenges I didn’t face.”

Some of those challenges include poverty, substance abuse, isolation, unemployment and lack of basic resources, including law enforcement.

“There are some reservations that don’t even have their own police departments or rely on Bureau of Indian Affairs — but they don’t really enforce the law that much,” Dyer-Redner said. “Many drugs are being sold out of houses in plain sight but nothing’s being done. When that happens, things get skewed.”

Dyer-Redner said it’s not all gloom and doom. He’s also witnessing the other side of humanity — selfless acts, good deeds and surprise friendships on the road. They include: Bird from Lovelock, Nevada, who teaches underserved youth traditional Paiute songs; Pete, an 82-year-old man who is walking across the United States and who stopped to share his story; and Deb, who heard about Dyer-Redner through Facebook and posed for a selfie at a Native American landmark at Pyramid Lake, 40 miles northeast of Reno.

Dyer-Redner is keeping a daily journal and recording his trip using a GoPro camera. His thesis will include these mediums as well as the many lessons he is learning along the way.

“I feel like I’ve definitely changed,” said Dyer-Redner, who wants to host a weeklong creative writing workshop for youth in the area in the future. “I feel more humble and possess a stronger sense of community. I feel like I’ve achieved great things as an individual, but it’s no longer about that.

“I’m part of a community, and now I have a responsibility to them.”