Gaming has come a long way since the flashing lights and plinking sounds of 1980s corner arcades. What once was denigrated as a ne’er-do-well’s pastime is now revered as a legitimate intellectual pursuit — one that can even help pay for college, as it did for a group of six Arizona State University students this past weekend.

Together, they beat out more than 480 teams from 390 universities across the country in the Heroes of the Dorm tournamentThe Heroes of the Dorm tournament is part of a partnership between video-game developer and publisher Blizzard Entertainment and TeSPA, a network for collegiate eSports players. , in which teams of five compete in “Heroes of the Storm,” a multiplayer, online battle-arena video game for PCs. In the game, players battle it out in 20- to 30-minute rounds using heroes from many games, including Warcraft and Diablo.

All told, each member of the team walked away with up to $75,000 in tuition and cash for the remainder of their college careers, as well as brand-new PCs geared towards gaming.

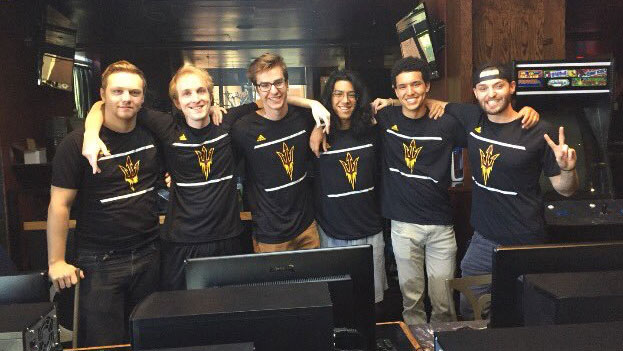

The Real Dream Team, as the ASU group dubbed themselves, consists of Stefan “akaface” Anderson, 26, a senior in criminal justice; Parham “Pham” Emami, 21, a junior in electrical engineering; Austin “Shot” Lonsert, 20, a senior in sociology; Isaiah “Snickers” Rubin, 21, a senior in civil engineering; Vann “Vannity” Childs, a senior in business and communication who plays as a substitute; and Michael “MichaelUdall” Udall, 20, a sophomore in business and the team’s pseudo captain.

“Honestly, it still hasn’t hit me yet,” Udall told ASU Now of the team’s win at the national competition. “It’s kind of surreal.”

Along with his team members, Udall flew to Seattle for the weekend of April 9-10 to compete at the CenturyLink Field Events Center. Livestreaming competitive gaming for an audience has been a common practice for years and has been growing in popularity — so much so that the phenomenon even has its own term: eSports.

And in true eSports fashion, the Heroes of the Dorm tournament was broadcast live on ESPN, YouTube and Twitch, a livestreaming video platform specifically for video games. ASU students even had the opportunity to view the competition in Wells Fargo Arena, where watch parties were held over the weekend as the team advanced.

The ASU Real Dream Team competes at the national Heroes of the Dorm video-game competition April 9-10 in Seattle. Top: The team is declared the winner.

Photos courtesy of Blizzard eSports

So with such a huge existing fan base and the limitless possibility for connection via the internet, is gaming the sport of the future?

Udall sure thinks so.

“From a numbers standpoint, it gets the same viewership as traditional sports,” he said. “And it’s weird because the numbers are there, but the money and the support wasn’t there for a while. It’s just barely starting to get there now.”

ASU research professor Joel GarreauJoel Garreau is the Professor of Law, Culture and Values in ASU’s Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law. He is also affiliated faculty in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society. knows what he means. Garreau is a founding co-director of Emerge, an annual event at ASU that bills itself as “the largest, smartest and most surprising carnival in America that brings together artists, engineers, dancers, scientists, storytellers, athletes, ethicists and technologists to imagine and build futures in which we can thrive.”

The theme of Emerge 2016 is “The Future of Sport 2040.” Appropriately, one of the April 29 event’s “visitations from the future” will be dedicated to eSport.

Corroborating Udall’s lament over the lag in support of a stable infrastructure compared with the popularity of eSports, Garreau referred to a quote from the famed sci-fi author William Gibson: “The future is already here — it’s just not evenly distributed.”

“The ASU [Heroes of the Dorm] team is a classic example of that,” said Garreau.

However, among those more familiar with the competitive gaming scene, there is great respect for the skill and dedication of the players.

To prepare for the Heroes of the Dorm tournament, Udall said his team practiced anywhere from four to six hours a day together and one to two hours individually, six days a week, for two and a half months.

“It takes an incredible amount of commitment to play at a high level, just like any sport,” said ASU associate professor Judd RuggillJudd Ruggill is an associate professor in the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences, an academic unit in ASU’s New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences at the West campus..

Ruggill co-directs the Learning Games Initiative, a transdisciplinary, inter-institutional research group that studies, teaches with and builds computer games, and also serves as a faculty adviser to the ASU student eSport club Next Level Gaming, or NLG.

“[Competitive gamers] are just like student athletes. It’s very much like that, with the idea that practice makes perfect,” Ruggill said.

The ASU Real Dream Team (from left): Austin Lonsert, Stefan Anderson, Michael Udall, Parham Emami, Isaiah Rubin and Vann Child. Photo courtesy of team

And though a large part of competitive gaming is cerebral — according to Garreau, “these athletes’ biggest muscle is between their ears” — Ruggill points out that that’s not all there is to it.

“It requires hand-eye coordination, a certain speed with which you can make actions on a keyboard,” he said. “There are even games in which the action per minute is a key metric.”

Still, Ruggill concedes, the types of injuries one might endure in eSports are far less severe than those associated with more traditional physical sports.

“You might get carpal tunnel syndrome or temporary eye problems, but nothing like a concussion,” he said.

And that may be part of the appeal for some people, along with the fact that eSports don’t require genetic predispositions for things like height or brawn. They don’t even require much special equipment — aside from a strong internet connection and a “halfway-decent machine,” according to Ruggill.

A strong internet connection is truly key, agrees Garreau. After all, it’s what allows for eSports to have such a wide reach. People show up in vast numbers just to view livestreams of competitions, he said; it’s a huge spectator sport that “has been known to fill 40,000-seat stadiums in Korea.”

Garreau hopes that kind of draw will hold true for this year’s eSport “visitation from the future” at Emerge, which will feature the final competition of a seven-week League of Legends tournament, projected live onto Jumbotrons in Wells Fargo Arena. The competition will, of course, be streamed on Twitch and will also feature a spirit squad cheering on players and people dressed as characters from the game.

If that doesn’t sound like a bona fide sporting event, we don’t know what does.

More Science and technology

AI and robotics researchers at ASU work to keep people safe, healthy

As Arizona State Unviversity continues to shine in U.S. patent rankings, robotics and artificial intelligence garner a growing percentage of such technologies. Two faculty members among the…

A new chapter in national security research at ASU

In 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite, into a low orbit around the Earth. Only the size of a beach ball, the satellite sent shock waves through the United…

One ASU researcher’s fix for freight’s costliest miles

America’s freight system is a miracle of modern logistics — until it isn’t. One snowstorm, one labor shortage, one delayed truck outside a major hub, and the whole process starts to wobble.…