You’ve come a long way, ASU.

Arizona State University has long had female teachers, but some of the biggest gender-equality strides came during the 1960s and the women’s liberation movement. As Women’s History Month wraps up, it’s a good time to look back at those who were firsts in their areas at ASU.

There have been female teachers from the beginning — Augusta Hildebrant (English, history and geography) and Mary R. Spafford (math, drawing and bookkeeping) were there when the college opened its doors — and as the decades went on, more women joined the faculty, most often in the areas of education, nursing, English and home economics.

But it wasn’t until the ’60s when women began to permeate areas like engineering, history and anthropology.

One of those women came to Tempe with her husband for a position in the College of Engineering.

Engineering a change

In 1966, Arizona seems like an exciting prospect for the young married couple headed West. Mary Anderson-Rowland — who had her doctorate in mathematical statistics from the University of Iowa — recalled being shocked on their first visit to ASU after driving to the campus on Southern Avenue, a gravel road at the time.

The university had positions for both Anderson-Rowland and her husband, Bruce Anderson, in the Department of Mathematics in the College of Engineering. In 1974, Anderson-Rowland joined the Industrial Engineering Department as the first female faculty.

“I will tell you that the men did not throw a party,” she said. “They did not celebrate that they finally had a woman in engineering.”

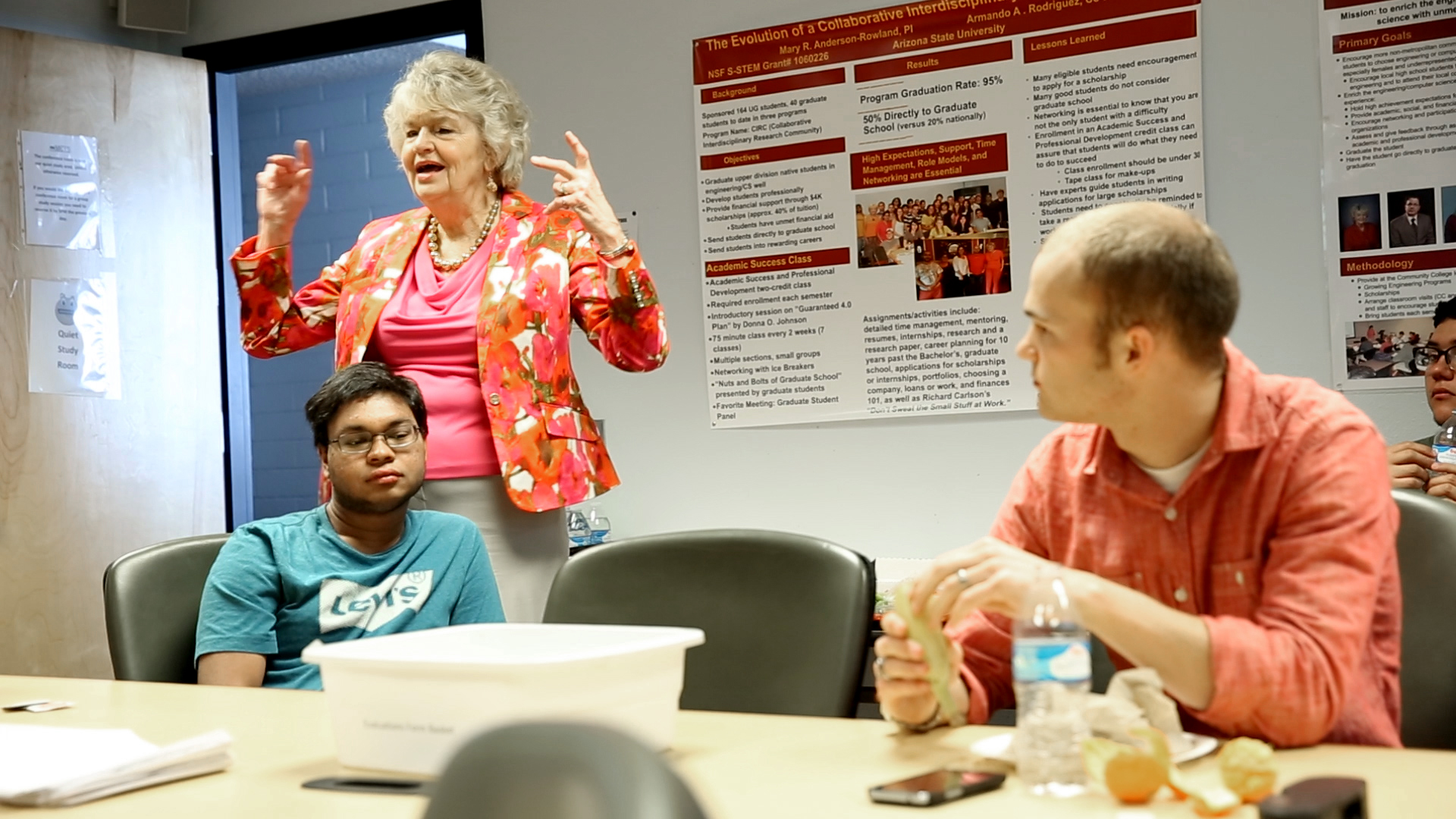

Associate professor Mary Anderson-Rowland, who joined the ASU faculty ranks in 1966, speaks to students in her senior design course for industrial engineers on the Tempe campus.

Anderson-Rowland — today an associate professor of Computing, Informatics, and Systems Design Engineering in the Ira A. Fulton Schools of Engineering — described a man who tried to shame her for having two jobs in her family where there were some men with no jobs. Another time while introducing herself as a member of the engineering department, she recalled, a male faculty member sing-songed, “I don’t think so” twice, regardless of the fact that his office was just a few doors down from Anderson-Rowland.

“The women coming in today don’t have to go through that,” said Anderson-Rowland, whose first husband, Bruce, died in 1992.

She saw her position in the engineering department as an opportunity to visit high schools and encourage women and underrepresented minorities to go into engineering, fighting the perception that those groups couldn’t make it in the male-dominated engineering school. She also spent 11 years as an assistant dean of student affairs and spent time advocating for the inclusion of women and minorities at an administrative level.

Today, the ASU veteran is the principal investigator of a grant program working with community colleges to produce more engineers. She feels that these students are the next disadvantaged group when it comes to inclusion in engineering. She describes a student, the first in his family to attend college of any kind, who was dissuaded by counselors to even try. He graduated with a degree in electrical engineering and is on a fellowship in graduate school at the University of Iowa.

“That’s what keeps me going, students like that.”

Making history

The same year Anderson-Rowland arrived in the Valley, so did Retha Warnicke with her husband, a lawyer, and their son. She joined the history department that year, later taking a short break to return to Harvard to complete her doctorate before returning to ASU in 1969.

“I was the first female hired on a tenure-track line, and I was the first woman to go through the various processes to become a professor,” said Warnicke, today a professor of history in the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

History professor Retha Warnicke, who also joined ASU in 1966, will teach two courses this fall, on English history and the Tudor monarchy.

“These were the bad old days,” she said of the process to defend her tenure position. There were concerns that she might not be serious about wanting the job because she had a husband employed as a lawyer.

“Can you believe that? I have a PhD from Harvard! I was spending all those years (studying) because I didn’t have anything better to do,” Warnicke said with a laugh.

“Women weren’t being hired in those days in history departments. The English department had some women, nursing and some specialized departments, but political science, history in particular, had never employed any women.”

Many women weren’t pursuing graduate school because the general feeling was that grad school wasn’t an opportunity for them. So not only did that shrink the pool of qualified women for the tenure positions, but because the men hadn’t studied in grad school with women, “they were less prone to look for women to be hired,” Warnicke said.

Warnicke worked hard to keep her personal life independent from her work life. She and her husband tried their best to time their daughter’s birth during winter break, but instead she was born on Nov. 20, before classes were over. Warnicke took off only one week of school and was back in time for finals preparation, returning to a standing ovation from her students.

During her 50 years at ASU, Warnicke has advocated for diversity on the staff and aimed to see more historians from minority backgrounds included in the department. She continues to teach, including two courses in the upcoming fall semester on her specialized subjects — English history and the Tudor monarchy.

“Students have changed over time,” she said. “I’m still here, I’m 76 years old. I’m still here and I still enjoy my students.”

An evolution

Leanne Nash became the university’s first primatologist when she joined ASU in 1971, after receiving her doctorate in anthropology from the University of California Davis.

“I was lucky to come into a field with a lot of female role models,” she said.

Nash was the Department of Anthropology’s first female faculty member, though she was joined by three other women in the following three years.

“There were some people with attitudes that were not entirely welcoming of females, but for the most part in anthropology that was not the case,” she said.

Leanne Nash, who retired in 2012, is shown working in her galago colony on the ASU Tempe campus (year unknown). She reversed the light cycle for the nocturnal animals in order to have a teaching colony.

Nash started her career working with Jane Goodall in Gombe National Park, focusing on baboons and mother-infant interactions; her work was cut short after three researchers were kidnapped from the park. She later shifted to a focus on galagos, small nocturnal primates commonly known as bush babies, and developed a colony in a room of the School of Human Evolution and Social Change.

“I started the galago colony here because we had a very small space that was indoors and I thought, ‘Well, I can reverse the light cycle and have a teaching colony where people can actually watch animals, and watching any animal develops skills for watching any other animal,’ ” she said. Nash’s work extended to the Primate Foundation of Arizona and the Phoenix Zoo and researching plant-gum ingestion in lemurs and small-bodied animals.

Nash, who retired in May 2012, sees a situation that plays out differently for women today.

“I think it’s more important that women get promoted,” she said. “There have been studies done in my specific area in biological anthropology which show that it’s still the case that women, although they’re equal or more and coming into the field with PhDs, they don’t get promoted as fast and they don’t get tenured as frequently, in general across the country.”

Comparing today

These women were part of a wave of intellectual pioneers who challenged cultural assumptions that women couldn’t teach and conduct research. Attitudes were changing in the 1960s and ’70s, throughout the university.

Harry K. Newburn, ASU’s 12th president, showed the administration’s support of the growth of female faculty when he was quoted in an Aug. 2, 1970, article in the Arizona Republic:

“A woman having the qualities of intellectual capacity, determination and a deep commitment to learning ought to be encouraged and supported in her ambitions; and the obstacles which misguided tradition and society have historically placed in her way should be removed,” he said.

That same article stated that there were approximately five male faculty for every female faculty member (825 to 159). In the fall of 2015, in contrast, women made up more than 45 percent of the faculty ranks (1,552 women, 1,857 men).

It’s part of the continued changes at an institution where inclusion and access are driving characteristics.

“It is 2016, I came in 1966, so it’s 50 years this semester that I’ve been here at ASU,” Anderson-Rowland said. “If I think back on that, I think how could I spend 50 years in one place? And I have to tell you it’s been very varied and it’s been exciting. ASU has been good for me; it’s been a good place to be for 50 years.”

More Sun Devil community

Dean’s Medalist finds freedom — and a second chance — in literature

When Phoenix resident Wade Sharp was last sent to what he termed “the hole” — solitary confinement in a county jail — he wasn’t sure how long he would be there.“COVID-19 was just starting out,” he…

University Archives chronicles more than 140 years of Sun Devil history

Editor’s note: This is part of a monthly series spotlighting ASU Library’s special collections throughout 2024.What was the name of the butcher who bequeathed the first piece of land that…

3 outstanding ASU alumni named The College Leaders of 2024

Three outstanding Arizona State University alumni from The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences will be named as this year’s slate of The College Leaders. The honor recognizes alumni for their…