Students at the Thunderbird School of Global Management pride themselves on cultivating an open spirit and a global mind-set.

So it’s no surprise that one of oldest clubs on the Glendale campus is rugby, which is played around the world and has a jovial culture in which opposing teams party together after a match.

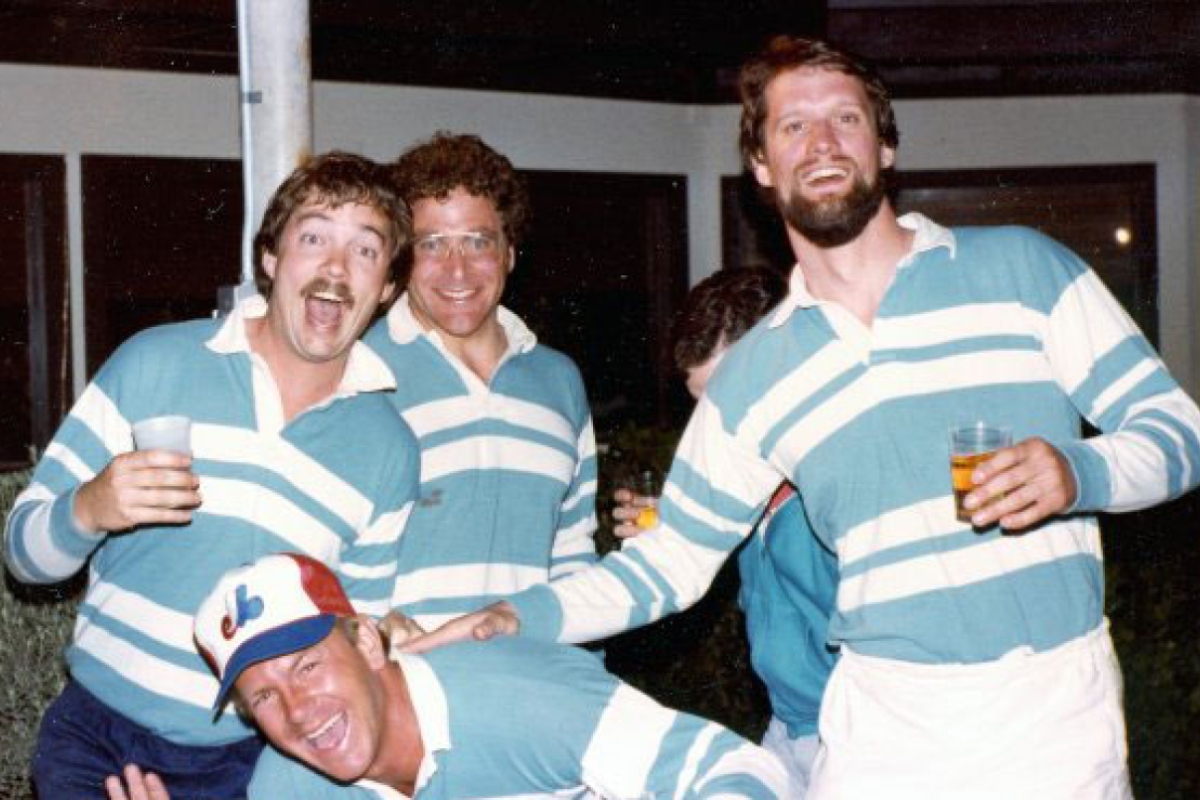

Next month, more than a hundred alumni of the rugby club will gather to celebrate their legacy, which includes promoting Thunderbird’s mission around the world.

The Thunderbird Rugby Football Club is celebrating its 40th anniversary this year, and the reunion will include a match between alumni and current players on April 9. Typically, the rugby reunions are held in March, but this year the alumni decided to move their get-together to coincide with Thunderbird’s 70th-anniversaryThunderbird, which was built as a World War II airfield, became the American Institute for Foreign Trade in 1946. Later, the school changed its name to the Thunderbird School of Global Management, and it became part of ASU in 2015. celebration weekend.

Rugby is a rough-and-tumble sport, and its beginnings at Thunderbird in 1976 were equally as scrappy. A group of students decided to form a rugby club, and on the first day of the fall semester, they recruited players from the guys who were standing in line for orientation. Jim Emslie was part of that first team.

“They asked me, ‘Have you ever played rugby before?’ And I said, ‘No, but I’d like to know. I understand they drink a lot of beer.’

“Some of us had played before, some of us hadn’t,” Emslie said of that first team.

They competed against alumni teams from ASU and the University of Arizona, plus the Phoenix Rugby Club and a team that came down from Las Vegas.

“They were mostly bouncers,” he said.

Emslie said that because of the global nature of Thunderbird, the team included players who had competed internationally.

“We had a few ringers. We probably won about half of our games, but we were always competitive, especially in the post-game activities,” said Emslie, who continued to play rugby while working in Venezuela for a few years after graduating from Thunderbird. He’s now an investment banker in California.

Back in the 1970s, the campus was still pretty isolated.

“There wasn’t a whole lot to do but sit around the pool or play tennis, so the matches became quite a campus event,” he said.

A few years after graduating, Emslie was back on campus and suggested a game between alumni and current players. That launched RAW — the Rugby Alumni Weekend.

Those get-togethers continued informally for several years. Then Chuck Hamilton, a rugby player who graduated in 1991, took the club and the reunions to the next level in the late 1990s.

“I started researching old rosters, trying to go all the way back. I would find guys via e-mail and ask, ‘Who did you play with?’ I looked at alumni lists and pulled names of guys who listed rugby as an activity,” Hamilton said.

He had the alumni club incorporated as a non-profit and began organizing international tours.

“Thunderbird being Thunderbird, we couldn’t just go to the usual places, like the UK or Australia,” Hamilton said. “We had to go off the beaten path.”

So the first tour, in 2003, was to Cuba, which was still off-limits to tourists then. The visit was arranged with the help of a professor at the school, and the players visited museums and other cultural attractions in between matches.

The Thunderbird "Old Boys" alumni rugby team played in Cuba in 2015.

Since then, the alumni, known as the Thunderbird Old Boys, have traveled to Argentina, Iceland, Croatia and Montenegro and then back to Cuba last year, just after it opened to U.S. tourism. The visits usually get a lot of local media attention. The match in Cuba was broadcast by a Chinese TV station.

“It’s been one way to give back to the school by going to other countries, passing out programs that talk about the history of the school and the curriculum,” Hamilton said, adding that he will typically try to have some of the program printed in the local language.

The team members — both current and former — reflect the global nature of Thunderbird.

“When I look at my roster, I see people from Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Canada, Japan, Taiwan, Singapore, India, Dubai and all over Europe,” said Hamilton, who coaches the rugby team at Northwestern University and also works a corporate job.

So far, the biggest reunion has been 80 players, but Hamilton said that 110 are committed to attend next month, including 17 of the founding players from 1976. The April event will include spring-training baseball games, skeet shooting, golf, the traditional “pub night” on campus, the alumni game and a banquet.

Hamilton also added a networking event, so the current players can better connect with the alumni.

Patrick Shields, president of the current club, said the players are looking forward to the reunion. The Thunderbird Executive Leadership Council has paid for the club to have special commemorative jerseys made for the anniversary.

“We can definitely see the bond that comes with being on the team,” he said.

Shields, who got his undergraduate degree from ASU, is pursuing a master’s degree in global management at Thunderbird. He said the players always find it a challenge to juggle graduate studies with the team’s seasonThe Thunderbird club is in the Arizona Rugby Union., which is going on now.

“There are some late nights. But I’ve talked with alumni who told me, ‘Sleep is overrated. Try to take part in as many things as you can.’ “

The alumni said the camaraderie of rugby culture is a key part of the game.

“I’ve coached high school sports and been involved with a lot of sporting activities, and I’ve never seen a sport that has that tradition, where after a game you get to know each other before going your separate ways,” Emslie said.

He said the connections remain strong.

“From college and post-college and the first place I went to work, the people I stay in touch with the most have been my rugby friends from Thunderbird,” he said.

“There’s a bond that is not severable.”

Top photo: Alex Marino gets tackled by Cody Payne as Rafael Salamanca comes to help out during a three-on-four scrimmage on March 15 at Thunderbird School of Global Management in Glendale. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

More Local, national and global affairs

Arizona public universities work together to predict housing insecurity before homelessness strikes

The words “housing insecurity” conjure up the image of a family living in a car after losing their home, frantically seeking an affordable new place to live.What if there was a way to predict housing…

A record 9 ASU students awarded US Department of State’s Critical Language Scholarship

Nine Arizona State University students have been selected for the highly competitive Critical Language Scholarship, or CLS, program — an initiative of the U.S. Department of State that aims to…

Putting hope above hate at antisemitism conference

Hatred and hope were the overarching themes of the “Rising Above Together” conference hosted April 11 by the Anti-Defamation League in partnership with Arizona State University.Hatred: According to…