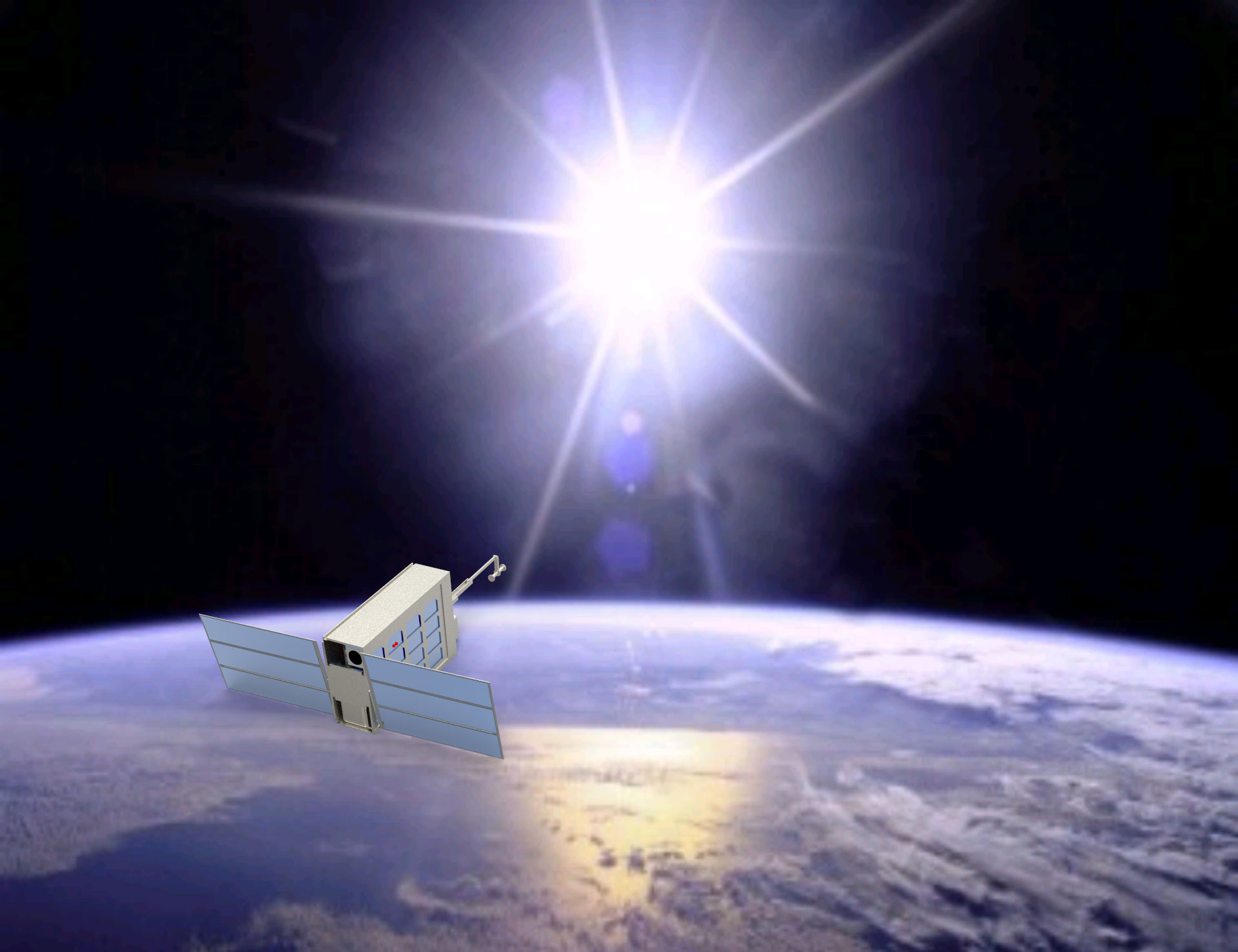

The U.S. Air Force has selected Arizona State University to build a spacecraft to monitor threats from outer space.

The satellite’s unblinking eye will search for meteor strikes and plasma eruptions from the sun that could wipe out everything electrical on Earth.

“Half the experiment is to look at the sun,” said Erik Asphaug, professor of the School of Earth and Space ExplorationThe School of Earth and Space Exploration is an academic unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. (Ronald Greeley Chair of Planetary Science) and co-principal investigator of the mission. “Half the experiment is to look down at the Earth.”

The Space Weather and Impact Monitoring Satellite (SWIMSat) will be a shoebox-size spacecraft designed and built by students under the guidance of Asphaug and co-principal investigator Jekan Thanga, assistant professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration and head of the Space and Terrestrial Robotic Exploration Laboratory.

ASU students will design and build everything but the propulsion system for the shoebox-size Space Weather and Impact Monitoring Satellite, or SWIMSat. Image by Robert Amzler/SpaceTREx

Everything but the propulsion system will be built at ASU. ASU was one of 10 universities selected out of 45 to be part of the Air Force Research Lab’s university nanosatellite program. The satellite is expected to launch in 2019 for a two-year mission.

“The Air Force is eager to extend and build capabilities in universities, and to use students to do that,” Thanga said.

The selection is for a two-year comprehensive design phase, after which the mission is expected to proceed with a two-year build phase and then launch. That is a deliberate pace — Asphaug thinks they could be done with Phase A in a year — but the Air Force really wants students to take the reins and learn and make and recover from mistakes, and design it and build it themselves.

“The goal is to make kids smart,” Asphaug said. “You can come in here as a student and see it all the way through to the end.”

SWIMSat will be an orbiting observatory doing two things:

1. Look down at the Earth for meteors. “With Chelyabinsk, any time something happens, people are looking at the web to see what happened,” Asphaug said, referring to the meteor that dramatically exploded over a Russian city in 2013. “These aren’t asteroid-sized bodies. They’re about the size of this office. ... We’re not monitoring the big asteroid that’s going to hit the Earth and kill us all. That’s going to be detected by telescope long in advance. By the time you see it going through the air it’ll be too late. But you can understand the flux of it and correlate the effects of impact.”

The Departments of Energy and Defense have been collecting this data, but they don’t release any of it to the public.

“They have cameras and data they don’t want anybody to know about,” Asphaug said. “They have spacecraft that are dedicated to looking at the Earth and looking for flashes, but there is no public data. … Basically there is no raw data for scientists to do anything with. We would be providing the first data from space of meteors striking.”

One of the jobs of the SWIMSat will be to observe meteor strikes on Earth. Ever wonder what a meteor looks like from above? This image, taken from the International Space Station during the August 2011 Perseid meteor shower, gives a glimpse. Photo by Ron Garan/NASA

Other questions SWIMSat may answer: Are a few small meteors precursor to a big one? Do they come in clusters? What is their geographic location?

“You could hit the alarm button for radar searches,” Asphaug said. “You would want any future monitoring satellites to be reliable. … That’s what we’re going to work on. For the meteors, the same. You’d want (satellites) to command telescopes on Earth to swing in a certain direction.”

The SWIMSat team will also be developing data-processing techniques. SWIMSat will be shooting thousands of frames per second. “You can’t beam all that data down,” Asphaug said. “One of the limitations of these things is propulsion, and the other is communication.”

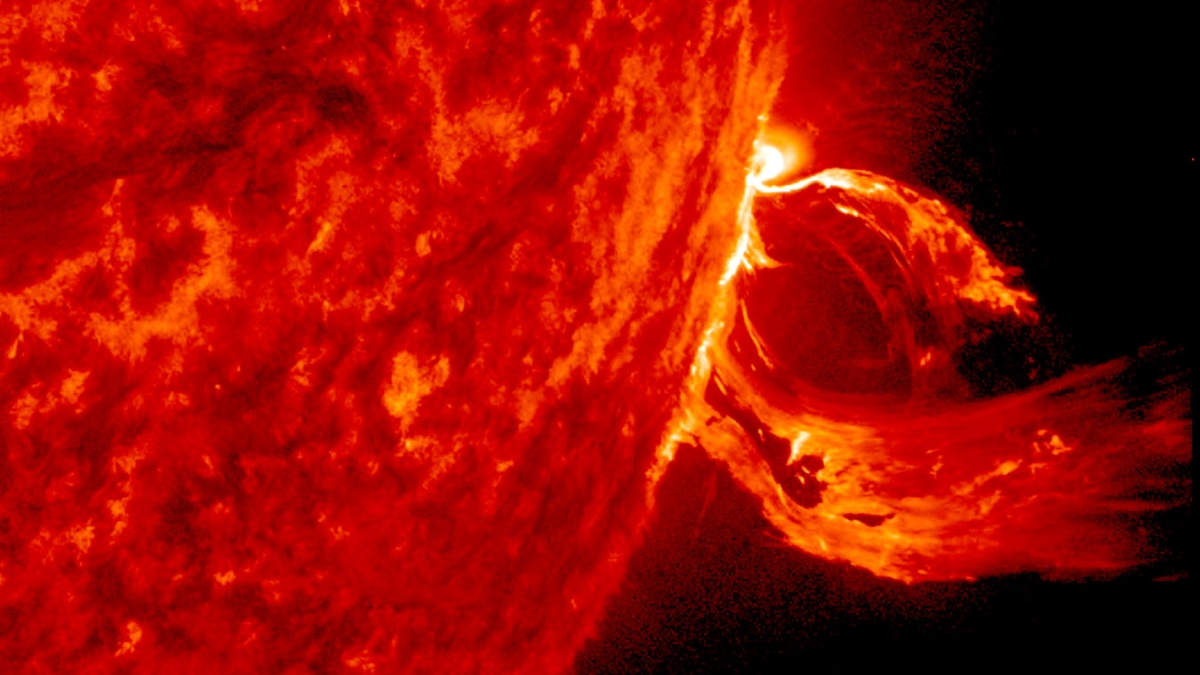

2. The spacecraft’s other job will be to monitor coronal mass ejections from the sun that could wipe out communications.

“Being able to not just see it, but to deal with the data onboard and detect an event.” Asphaug said. “It would also collect a lot of useful data. It’s not like people haven’t looked at the sun before; it would be a novel way of doing this from deep space.”

The Air Force is interested in coronal mass ejections from a space-weather point of view, Thanga said.

“What everyone is really scared of is the Carrington Event,” he said. “It was in the middle of the Industrial Revolution. We were just starting to have telegraphs. The impact on the Earth’s magnetosphere was so much that many electric devices were zapped by intense radiation seeping through the magnetic field.”

The Carrington Event, also known as the Solar Storm of 1859, was a powerful geomagnetic solar storm. A solar coronal mass ejection hit Earth's magnetosphere and induced one of the largest geomagnetic storms on record. Aurorae were seen as far south as the Caribbean. Telegraph systems in Europe and North America failed.

“If (that) were to happen now, there was a 2008 study done to see if a Carrington Event happened now, what would be the impact on the United States?” Thanga said. “They said 10 years of no electricity. Like some of these sci-fi movies, it would be a post-apocalyptic situation. We right now have no way to prevent it or avoid it.”

“The goal is to make kids smart. You can come in here as a student and see it all the way through to the end.”

— ASU professor Erik Asphaug on the Air Force wanting students to take the reins on building the satellite

Solar-monitoring satellites, loaded with instruments, are in place, but they don’t have total coverage of the sun.

“You’d benefit from total 360-degree coverage of the sun,” Thanga said. It would allow for more comprehensive monitoring and data collection.

“That could be used just like earthquakes,” he said. “If you had some kind of warning, you’d have some time to take some safety steps.”

Because any coronal mass ejection leading to another Carrington Event would take at least a day to reach Earth, there would be enough time to ground airplanes, shut down power grids and move the International Space Station to the other side of the planet. “Bury your electronics,” Thanga said.

“It’s this idea of buying yourself a couple days’ lead time,” Asphaug said. “In that sense SWIMSat would be a pioneer in this kind of monitoring. It would give you reliable warning. … Coronal mass ejections are easy to see and detect.”

Both missions would be conducted simultaneously, back and forth between the Earth and the sun.

“The cadence depends on the orbit we are taking, and also on what we are discovering, and how students are progressing with the data on the ground,” Asphaug said. “For instance, we might collect meteor data while the solar coronagraph students work on the data they have collected, and vice versa, every few months. This allows us to iterate how we collect the data, and how we preprocess the data onboard the spacecraft (frame stacking, event thresholds) to decide what is downlinked.”

Asphaug will act as the science principal investigator and Thanga as the engineering principal investigator. As students build SWIMSat, both will act as an advisory board.

Co-investigators include Paul Scowen, associate research professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration; Hugh Barnaby, associate professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering, Ira A. Fulton School of Engineering; and Eric Adamson, National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration and University of Colorado Boulder. Adamson, a former postdoc at ASU, came up with the coronal mass ejection detection idea using a CubeSat network and Erik Asphaug with the meteor impact monitoring idea and extension to a network.

Top photo: A substantial coronal mass ejection, or CME, blew out from side of the sun on June 17-18, 2015. While some of the plasma fell back into the sun, a look at a coronagraph showed a large cloud of particles heading into space. Photo by NASA/Solar Dynamics Observatory

More Science and technology

ASU professor shares the science behind making successful New Year's resolutions

Making New Year’s resolutions is easy. Executing them? Not so much.But what if we're going about it all wrong? Does real change take more than just making resolutions?Michelle Shiota thinks so. …

ASU student-run podcast shares personal stories from the lives of scientists

Everyone has a story.Some are inspirational. Others are cautionary. But most are narratives of a person’s path, sometimes a circuitous one, from one point in their lives to another.A new podcast…

The meteorite effect

By Bret HovellEditor's note: This story is featured in the winter 2025 issue of ASU Thrive.On Nov. 9, 1923, Harvey Nininger saw his future explode across the Kansas sky. He would become perhaps the…