Apart from hydrogen, as many have heard from the Carl Sagan and Neil deGrasse Tyson "Cosmos" series, every ingredient in the human body is made from elements forged by stars.

The calcium in our bones, the oxygen we breathe, the iron in our blood — all were forged in the element factories of stars. Even the carbon in our apple pie.

Stars are giant element furnaces. Their intense heat can cause atoms to collide, creating new elements — a process known as nuclear fusion. That process is what created chemical elements like carbon or iron, the building blocks that make up life as we know it.

It sounds pretty simple, but it is a very intricate process. And there are still many uncertainties.

Professors Sumner Starrfield and Frank Timmes, both from Arizona State University, and professor Christian Iliadis, from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, hope to resolve some of those uncertainties.

“Broad brush, we have a good idea that massive stars become one kind of supernova and binary stars with white dwarfs become another type of supernova. We know a lot about what may have caused the explosions, but there are many unexplained parts that need to be worked out,” said Starrfield, Regents' Professor in ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration.

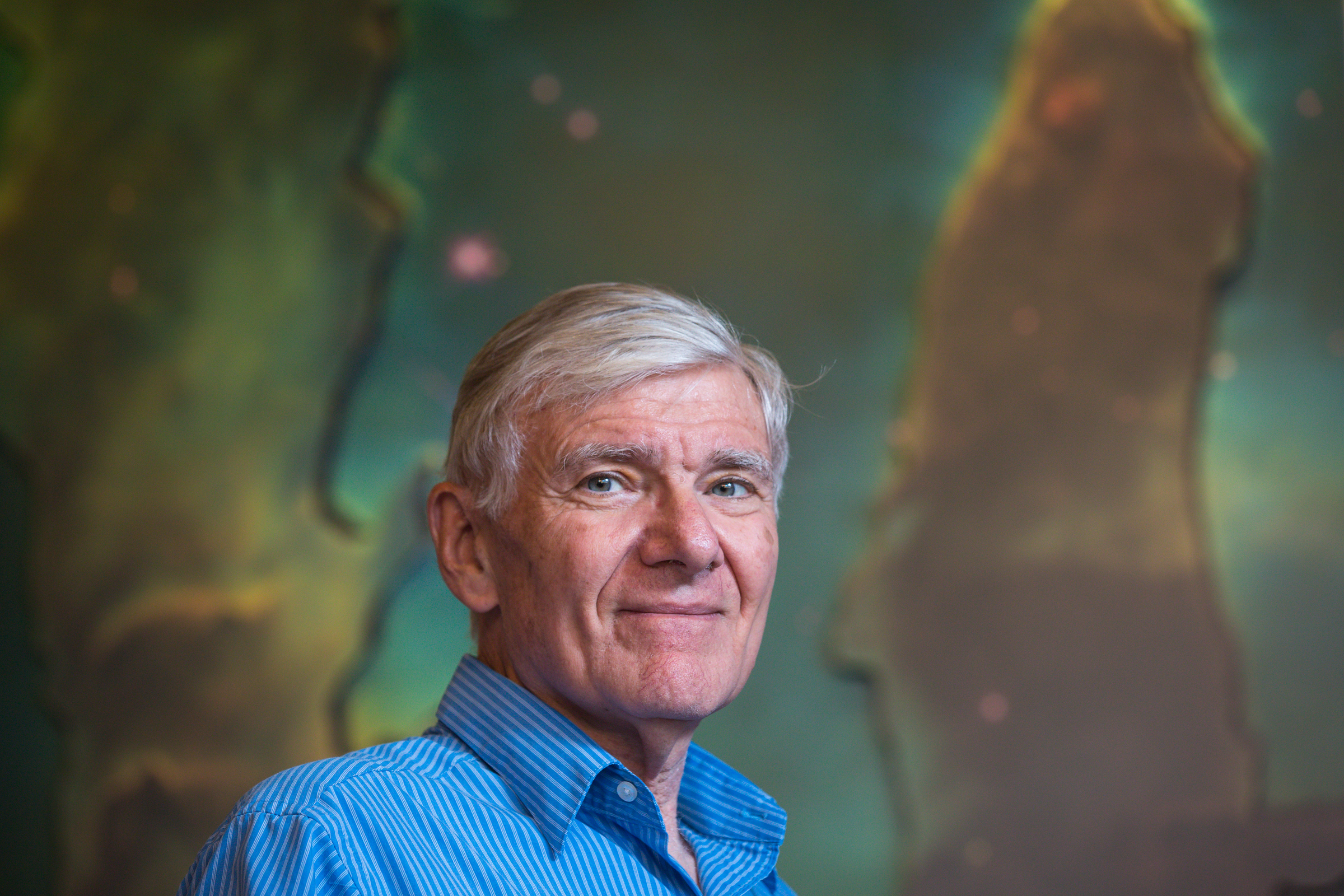

ASU professor Sumner Starrfield is a computational astrophysicist who has been studying stellar explosions for more than 30 years using ground-based optical and infrared telescopes as well as space-based ones such as the Hubble Space Telescope. In collaboration with colleagues Frank Timmes of ASU and Christian Iliadis at UNC, Starrfield is studying thermonuclear reaction rates to determine how much of certain elements exploding stars can produce. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

Inside these element factories, how much carbon for our apple pies gets made or how much calcium is available to make our bones depends on their nuclear reaction rates.

For example, as shown in the recent movie “The Martian,” if you were trying to make water, you would take hydrogen and oxygen and some energy and put it together in a container and it would make water at a certain rate depending on the temperature of the container. Add more heat, and the reaction speeds up, producing more water.

A similar thing happens inside stars — except it’s nuclear reactions releasing a factor of 1 million times more energy than a chemical reaction. Stars run on nuclear reactions. Smash together a carbon nucleus and a helium nucleus inside the furnace of a star, and out pops the oxygen we breathe. Speed up that reaction, and the star yields more oxygen.

Researchers use computers and solve equations to predict how a star evolves. Part of that input into how stars evolve are nuclear reaction rates. One set rate has been used to arrive at an estimate of how much of a certain element a star can produce. But is that number optimal? Is it some super optimistically high value, or it pessimistically low?

“What we will define is a meaningful range, given the uncertainties of what is measured here on Earth, of what actually comes out. At the end of the day, what we are going to know is the variation — how much variation is there in a star’s output. How much calcium or carbon comes out of the star?” said Timmes, an astrophysicist in ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration, which is a unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

Investigating the range of elements that a star can produce is based on what is measured in the terrestrial laboratory. This is where nuclear physicist Iliadis, who recently published a textbook on the nuclear physics of stars, fits in: He’s the experimentalist providing the data on the nuclear fusion reaction rates and their uncertainties.

“It is not quite 'The power of the Sun, in the palm of my hands,' as muttered by Dr. Octavius in 'Spider-Man 2'; nevertheless we do measure with our accelerator facilities the very same nuclear fusion reactions that occur in stars,” Iliadis said.

But uncertainties are inherent in lab measurements. What you want to do is connect what you do in the lab with what you see in the night sky. And that’s Starrfield’s contribution — he’s an expert in dead and dying suns. He will use the reaction rates from Iliadis in new calculations of how different types of stars can become supernovae.

This proposal ties in a tight loop experiments done here on Earth with observations in the night sky. For more than two decades Timmes has been doing modeling of stars; the models he creates will serve as the glue between what is measured on Earth by Iliadis and what is seen in the dark night sky by Starrfield.

The team is going to be checking roughly 50 of the most important nuclear reaction rates for producing elements that form the building blocks of life as we know it. And just as important, some of these reaction rates are useful in nuclear fusion experiments to produce clean power on Earth.

As a star ages, hydrogen and then helium nuclei fuse to form heavier elements. These reactions continue in stars today as lighter elements are transformed into heavier ones.

Late in life, most stars will explode, ejecting the elements they forged into interstellar space. If a star is heavy enough, or has a close companion, it will explode in a supernova that creates many heavy elements including iron and nickel. The explosion also disperses the different elements across the galaxy, scattering the stellar material that will eventually make up planets — like the creation of Earth.

Starrfield will compare their calculations with observations of exploding stars and determine the amounts of chemical elements blown into space. “We are the results,” he said.

(Top photo: NGC 2359 (also known as Thor's Helmet) is an emission nebula in the southern constellation Canis Major (The Great Dog). This helmet-shaped cosmic cloud with wing-like appendages is around 15,000 light-years away from Earth and is more than 30 light-years across. The central star of Thor’s Helmet is the Wolf-Rayet star WR 7. This large, bright star is believed to be about 280,000 times brighter than the Sun, 16 times more massive and 1.41 times larger. It is also in the last stage of its life. Professors Sumner Starrfield, Frank Timmes and Christian Iliadis will study the pre-explosion evolution of stars like WR 7.)

More Science and technology

Will this antibiotic work? ASU scientists develop rapid bacterial tests

Bacteria multiply at an astonishing rate, sometimes doubling in number in under four minutes. Imagine a doctor faced with a patient showing severe signs of infection. As they sift through test…

ASU researcher part of team discovering ways to fight drug-resistant bacteria

A new study published in the Science Advances journal featuring Arizona State University researchers has found vulnerabilities in certain strains of bacteria that are antibiotic resistant, just…

ASU student researchers get early, hands-on experience in engineering research

Using computer science to aid endangered species reintroduction, enhance software engineering education and improve semiconductor material performance are just some of the ways Arizona State…