For years John Carlson and Scott Ruston worked just steps from each other, but their paths never crossed.

Both men had spent their undergraduate years as Navy ROTC midshipmen before serving on active duty, both had later entered into the U.S. Navy Reserve and both had eventually found their way to professorships at Arizona State University — Carlson as an associate professor of religious studies in the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies, and Ruston as an assistant research professorRuston also conducts research in the Center for Strategic Communication. The Hugh Downs School of Human Communication is an academic unit of ASU's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. in the Hugh Downs School of Human Communication.

But it wasn't until they were both called to active duty around the same time that they actually met — in Djibouti, Africa.

“It was very coincidental,” Carlson said. “We had been walking [ASU’s Tempe] campus and had offices a hundred yards apart from each other and had never met each other before that. … It really wasn’t until I arrived in Djibouti and people said, ‘Wait a minute, there’s another scholar here with a PhD who’s from Arizona State. Now there’s two of you,’ that we started realizing this is quite unique.”

Before deployment, though, both Carlson and Ruston had to go through a bit of training — 19 weeks of Army infantry training condensed into three weeks, to be exact. Their “crash course,” as they endearingly refer to it, took place in South Carolina but at different times of the year.

“[I was] there in January. It was freezing cold; it was sleeting each night,” Ruston said.

Carlson’s training mercifully took place during a more temperate season.

“The weather makes all the difference. I went through it in September, and it was actually pretty nice. There were several people who were commenting, ‘There are a lot of people who would pay good money to do this!’” he recalled with a laugh.

The crash course involved rigorous training.

Said Carlson, “At a relatively late stage in life I found myself crawling through the mud and learning to do the low crawl, which simulates having gunfire going right above your head. … Doing simulated rollovers in a Humvee, lots of rifle and pistol qualifications, convoy operations — that kind of thing.”

And though Ruston admits there were those among them who had their doubts about the necessity of all that training, it ended up paying off.

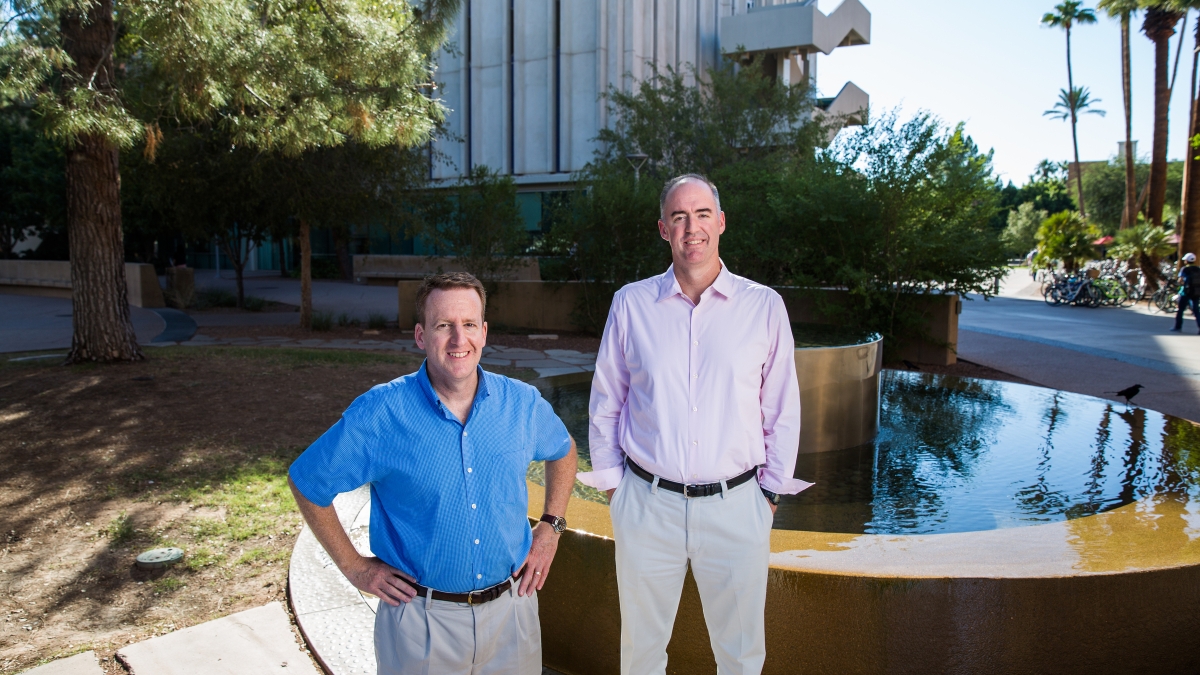

Capt. Scott Ruston, deputy director for theater security cooperation, makes opening remarks at the East African Theater Security Cooperation Conference at Combined Joint Task Force - Horn of Africa on Jan. 13. The conference brought together service members, civilian counterparts and ambassadors from across East Africa to discuss regional access and development. Top: ASU faculty John Carlson (left) and Ruston on the Tempe campus. Photos by Deanna Dent/ASU Now (top) and Staff Sgt. Carlin Leslie/U.S. Air Force

During his deployment in Djibouti, Ruston was suddenly reassigned to a project in Mogadishu, Somalia, roughly 1,100 miles southeast of Djibouti and the target of frequent terrorist attacks by the militant group Al Shabaab.

The heightened sense of danger meant heightened security measures. So instead of traveling by a regular car or bus, when Ruston and his men were on the move they traveled well-protected.

“If we were leaving the facility where our office was in Mogadishu, we were rolling in an armored personnel carrier. And I remember as I boarded this armed personnel carrier thinking to myself, ‘Boy, it’s a good thing I paid attention to all this training that I didn’t expect to use!’” Ruston said. “You just never know what’s going to happen.”

Ruston’s deployment in Djibouti lasted from January 2014 to January 2015, and Carlson’s lasted from September 2014 to June 2015 — so they had an overlap period of about four months during which they ended up working closely on a couple of projects.

Ruston worked as the deputy director for theater security cooperationas well as periods leading the Effects Division and the CJTF HOA Military Coordination Cell in Mogadishu, Somalia., which meant he was responsible for running communication efforts with partner nations in the East Africa region, supporting them in their efforts to combat Al Shabaab and carry out other stabilizing efforts that the African troops were engaged in.

Carlson worked as a liaison officer for the U.S. Embassy in Djibouti, where he was responsible for ensuring and maintaining a positive relationship between the U.S. ambassador to Djibouti and the commanding general of the Djibouti military forces, as well as making sure their common goals were pursued.

One of the projects Ruston and Carlson had the chance to work on together was a conference that would bring all the U.S. ambassadors throughout the East Africa region together at their base, Camp Lemonnier, for a strategic discussion.

“You would think it happens all the time,” Ruston said. “It never happens. It’s kind of a big deal.”

Ruston was lead planner for the conference, navigating all the red tape, bureaucracy and protocol involved.

Carlson's position in the embassy enabled him to provide vital support. For his part, he was in charge of U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry's visit to Camp Lemonnier. This was the highest-ranking U.S. official ever to visit the camp — or Djibouti for that matter.

Capt. John Carlson lectures students in his religion, war and peace class at ASU. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

The respective experiences were the highlights of their deployment for both men.

“That conference was pretty significant because getting that level of representation from the U.S. embassies … to participate from almost every country in the East African region was pretty remarkable,” Ruston said.

On that high note, his deployment ended, the very next day after the conference. Carlson’s deployment ended later that same year, in June of 2015.

The hardest part of their deployment, both men agreed, was having to leave their families.

“People sometimes tell me, ‘Thank you for your service,’” said Carlson, “and I’m like, ‘Don’t thank me, thank my wife.’ Because she’s a working mom, she’s a professional with her own career and she does that all day and comes home and still has to take care of kids, pack lunches and all that without my help.”

There was some solace for Carlson’s wife, though; during their deployment she and Ruston’s wife met for dinner and to socialize, acting as “a great source of consolation” for each other.

Now both back on the job at ASU, Carlson and Ruston are more enthused than ever to put their experiences to work.

“To be part of government life, when your job is to study politics from a scholarly perspective, I think it does help to provide some important grounding,” Carlson said.

As well, they both noted, it's one thing to study problems of religious extremism and violence; it's another thing to gain close-up appreciation of the dangers these threats pose and the challenges of confronting them.

The two hope to collaborate academically in the future.

“Our two centers collaborate, but we have not individually collaborated together leading up to the deployment,” Ruston said. “Since we’ve been back, we’ve talked about possible collaborations. Between our experiences in East Africa, what’s going in East Africa right now, what’s going on just across the straits in Yemen, and the work that our two respective centers do, there’s got to be some areas where we could work together and bring our military and scholarly insights together.

“So both in terms of social activities, as well as professional activities, we look forward to more collaboration."

More Arts, humanities and education

Local traffic boxes get a colorful makeover

A team of Arizona State University students recently helped transform bland, beige traffic boxes in Chandler into colorful works of public art. “It’s amazing,” said ASU student Sarai…

2 ASU professors, alumnus named 2025 Guggenheim Fellows

Two Arizona State University professors and a university alumnus have been named 2025 Guggenheim Fellows.Regents Professor Sir Jonathan Bate, English Professor of Practice Larissa Fasthorse and…

No argument: ASU-led project improves high school students' writing skills

Students in the freshman English class at Phoenix Trevor G. Browne High School often pop the question to teacher Rocio Rivas.No, not that one.This one:“How is this going to help me?”When Rivas…