Clutching hopes, dreams and minerals, about 50 people waited to approach Captain Fireball. Did they own interesting and valuable meteorites? Or just another rock?

With the speed and finality befitting his nickname, Captain Fireball — aka research professor Laurence GarvieLaurence Garvie is a research professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration, which is part of ASU's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences., collections manager of the Center for Meteorite Studies at Arizona State University — crushed dreams like a metal lump shattering a window.

There wasn’t time to waste. Saturday was Earth & Space Exploration Day at ASU. The open house, hosted by ASU's School of Earth and Space Exploration, features science-related activities for families, and it is the one day a year the public is invited to bring in what might be a meteorite for identification. The rest of the year, the center’s doors are closed firmly, as is stated — multiple times — on nearly every single page of the center’s website. The university’s meteorite identification program was closed five years ago because they were overwhelmed with requests.

“Nope,” Garvie said to one hopeful visitor. “It’s a pebble that has a shape to it.”

“No,” he said to another. “It’s not fusion crust. It just has some weathering on it.”

“The physical attributes of the sample are completely wrong,” he said to a gentleman who insisted he has something from space. (“I get one of those every time,” Garvie said.)

“You’re 100 percent sure it’s not a meteorite?” the gentleman insisted. He had a stack of data printouts. Tests have been done, he told Garvie, expensive tests.

“It’s not like any meteorite I’ve ever seen,” Garvie said. Captain Fireball sends the crestfallen but still insistent man downstairs to Dr. Rock, a geologist who was identifying rock specimens.

Laurence Garvie (left), collections manager of the Center for Meteorite Studies, examines a rock too heavy to carry at Saturday's Earth & Space Exploration Day.

This and top photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

Ron DePlazes did not have a meteorite either, but he was not disappointed. The Phoenix man owns a company that paints road cuts for state highway departments across the West so they’re not glaring white. You can see his work along the Beeline Highway on the way up to Payson.

“I paint rocks,” he said. He doesn’t collect them. “No, I don’t. I pick up Indian stuff. I like meteorites, though.”

DePlazes was walking across the yard of his business at Central Avenue and the Salt River with his son Wednesday morning when he spotted his sample.

It is heavy, and magnetic — DePlazes affixed two small magnets to the rock — but it’s not a meteorite. It is similar to the Argentinian Chajari meteorite, according to Garvie, who sliced a sample from it and analyzed it in his lab.

“They don’t know it’s not a meteorite, but they don’t know what it is,” DePlazes said. “He’s a lot more sophisticated than I am.”

Before coming in to the event, DePlazes carefully went over the meteorite ID page on the center’s website and answered the five questions on the page.

“I didn’t think I had a meteorite,” he said. But he wanted to come in and check anyway. “He doesn’t know what it is, and that’s amazing considering how much they know here at Arizona State,” he said.

Jeff Christensen drove in from Mesquite, Nevada, with a handgun case full of rocks. It was either drive south to Arizona State University or north to Brigham Young University to get them identified. Christensen found his rocks while he was working at the local airport.

“What are you going to do in Mesquite?” he said. “There’s 1,800 people. I just kick rocks when it’s slow.”

He didn’t have a meteorite either.

“He’s saying they don’t get those bubbles in there,” Christensen said. “That’s weird.”

Weird doesn’t even begin to describe the Myerscough saga. Rex Myerscough and his son, Rex Jr., drove two days from Clearwater, Florida, with a 76-pound rock that, could it communicate with a meteorite, would have a better story to tell than simply falling from space. It’s a story spanning a quarter-century of drama. Pay attention. It gets complicated.

The Myerscough saga began in 1972, when Rex Sr. bought three lots and built a house on one. In the process of prepping a second lot for construction, he found an unusual rock. He took it to the school where his wife taught and left it in a classroom as a curiosity.

After some years, his wife retired. Some time after that, the school principal called. A geologist had dropped by the school and said the rock was a meteorite. The principal didn’t want something that valuable in the school, so Myerscough picked it up and brought it home.

Myerscough repairs and maintains pressure washers for a living. NASA called him because they had a broken pressure washer. He told NASA he would fix it for free if they would identify his rock. It was a deal.

Then the deal fell through. The scientist who was slated to inspect the rock was transferred to a facility in Tennessee. It was disappointing, not least because of the effort it took to take a sample from the rock.

Lori, Kal (center) and Steve Baker chat with ASU research professor Laurence Garvie while examining a meteorite display at Earth & Space Exploration Day on Saturday in Tempe. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

“You had to take an 8-pound sledge and beat it and beat it just to get a little matchstick off it,” Myerscough said.

Then the rock was stolen from Rex Jr.

“I was robbed at gunpoint,” he said.

A suspect was taken into custody. The pair of detectives assigned to the case looked familiar to Mrs. Myerscough, and she looked familiar to them. It turned out she’d taught both of them in elementary school.

“The detectives said they had a white room,” Myerscough said. “They said, ‘We’ll take him in the white room and we’ll find out where it is.’”

The suspect confessed in the white room. The rock was buried under the monkey bars on a Catholic school playground.

“They sent a SWAT team out there and recovered it,” Myerscough said. “I go out there and there’s all these SWAT guys standing around looking at it.”

They thought it was a million-dollar meteorite.

Finally, in this multi-decade quest to identify the mystery rock, Myerscough found out about the meteorite identification event at Earth & Space Exploration Day. He and his son packed the rock in a sawn-off orange Home Depot bucket, placed it on a dolly, and took off for Arizona.

“I couldn’t send this thing off to Tennessee or wherever,” he said. “UPS wouldn’t take it. The airlines wouldn’t take it. It weighs 76 pounds.”

It took two days and more than 2,100 miles to drive from Clearwater to Phoenix.

“After all that, it’s not a meteorite,” Rex Jr. said.

The Myerscoughs, having solved the mystery, are taking the rock home, where they will keep it. Was the trip worth it?

“Oh, I’ve never been to this part of the country before,” Myerscough said.

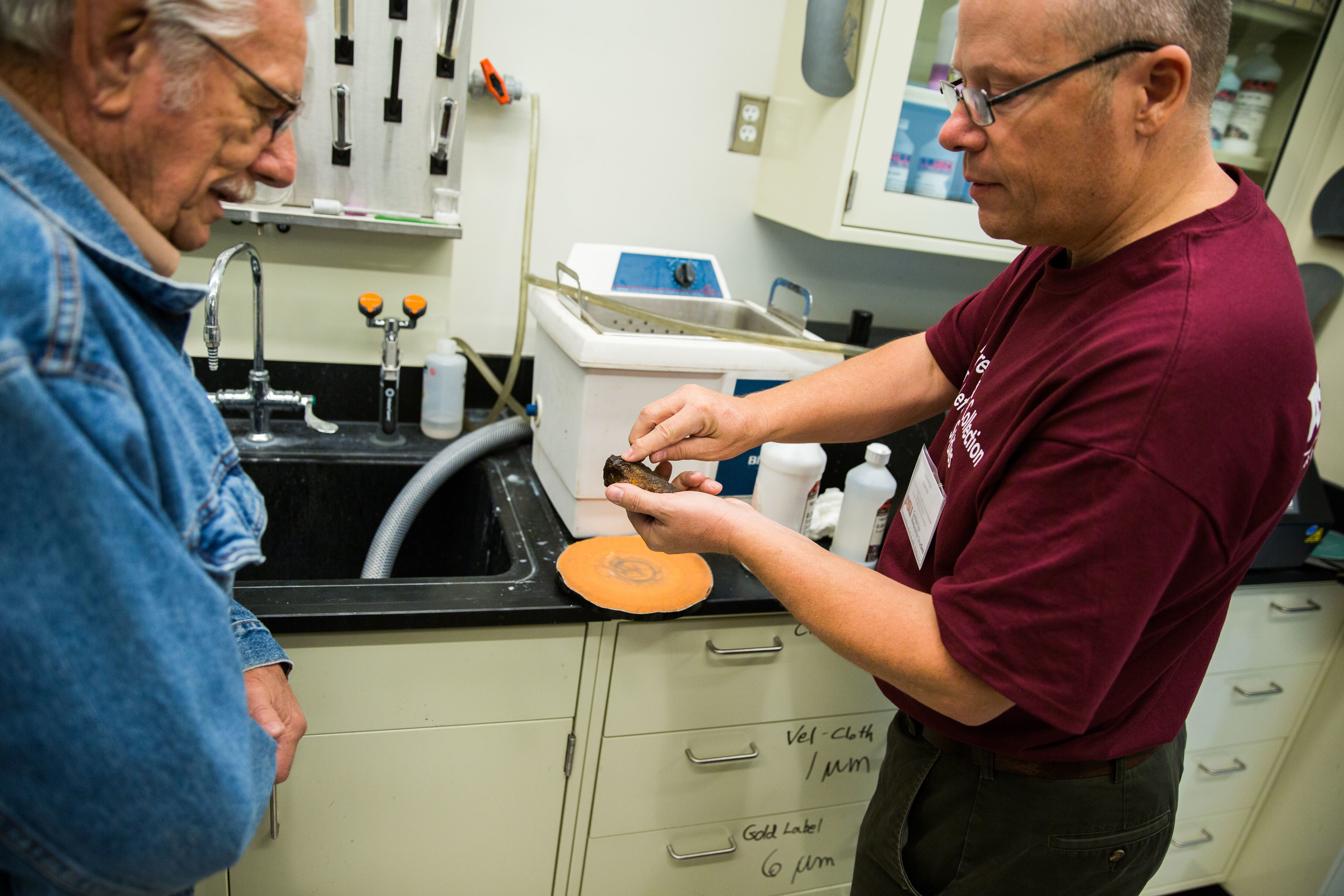

Laurence Garvie (right) explains to Ron DePlazes that by sanding the edge of the sample he can give a definitive answer whether his sample is a meteorite (it was not) Saturday in Tempe. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

Meanwhile, back at the identification table the carnage continued.

Hilarie O’Dell and her three children: “My husband found that camping by St. Johns. It’s not a meteorite?”

It turned out to be industrial slag. “It’s the most common ‘meteor-wrong,’ ” Garvie said. He gamely looked at it anyway — after all, this was a woman who had waited in line with three children — and pointed out all the reasons it wasn’t a meteorite.

Lane Agan from Show Low: “I saw it fall. Did I pick up the wrong rock?”

“It’s totally unlike a meteorite.”

A young man with a tiny box lined with white cotton holding two specks.

“You can’t tell from that,” Garvie said. “You brought in, like, one milligram. ... It’s the tiniest meteor-wrong we’ve ever had. From that tiny, tiny fragment, I don’t think it’s a meteorite.”

A pair of men with some twisted black rocks.

“Why did you bring this in? It’s a big piece of slag.”

After two hours of dream smashing, the line dissipated. Despite not identifying a single meteorite all day, Garvie marveled at what he had seen.

“The jar of tar-covered pebbles? That was fantastic.”

More Science and technology

How AI is changing college

Artificial intelligence is the “great equalizer,” in the words of ASU President Michael Crow.It’s compelled industries, including higher education, to adapt quickly to keep pace with its rapid…

The Dreamscape effect

Written by Bret HovellSeventh grader Samuel Granado is a well-spoken and bright student at Villa de Paz Elementary School in Phoenix. But he starts out cautiously when he describes a new virtual…

Research expenditures ranking underscores ASU’s dramatic growth in high-impact science

Arizona State University has surpassed $1 billion in annual research funding for the first time, placing the university among the top 4% of research institutions nationwide, according to the latest…