Regents' Professor discusses women's rights, race, reproduction

Throughout history, women have faced intense discrimination – from a lack of legal rights and very little independence from their husbands, to being thought to have inferior brains. In many societies, women have long been viewed as less than fully human.

American society has come a long way in recognizing and protecting women’s humanity and human rights. However, women will always be fundamentally different than men because of their ability to bear children. We are reminded of this by current political debates concerning abortion and contraception, which some have called a “war on women.”

What are the roots of gender inequality? How have the challenges faced by women changed over time? Sally Kitch, an ASU Regents’ Professor of Women and Gender Studies, has spent many years exploring the reasons why the world sees men and women so differently. To find answers, she has explored questions ranging from the gendered origins of race to American utopian communities.

The intersection of race and gender

Kitch, who is also the director of ASU’s Institute for Humanities Research, covered 300 years of history tracing the connection between gender and race in her book, "The Specter of Sex: Gendered Foundations of Racial Formation in the United States" (State University of New York Press, 2009). She discovered that gender inequities have been central to societies for centuries, but race is a very modern idea.

“One thing we know about race is that it doesn’t exist. It’s not a biological category,” Kitch says. Some believe that groups of people who share similar physiological characteristics constitute races, but race is really a system imposed by historical, cultural and political processes, Kitch says. Genetically speaking, a black and white person may have more in common than two people of the same race. How, then, did race become so significant?

European explorers of the sixteenth century noticed differences like skin color when they encountered natives of other continents, but they were even more interested in the unfamiliar sexual and reproductive practices of other cultures, Kitch says.

“The Europeans thought that cultures in which men and women weren’t that different in terms of their behavior or appearance were uncivilized,” Kitch says. Marriage customs, sexual practices, and even whether or not women experienced pain during childbirth (it was considered more civilized to feel pain) were all important distinctions used to disparage certain groups and, eventually, define races.

“That gave me the insight that racial characteristics really evolved on the basis of comparative gender characteristics,” Kitch says. “My work provides the backstory of the concept of intersectionality by showing how race and gender judgments evolved together and influenced one another.”

Differences in gender behavior also served as Europeans’ justification for using slavery to further their own economic interests. “When Europeans began to enslave Africans, they didn’t start with their skin color to explain why,” Kitch says. Instead, they used observations on sexual behavior and religious practices to decide the African culture was inferior.

A history of discrimination

To understand how gender continued to influence race over time, Kitch traced five racial groups in the U.S. from the Colonial period to the mid-20th century – American Indians, African-Americans, Latinos, Asian-Americans and European whites. After exploring the roots of racial formation, she focused on the categories of bodies, blood and citizenship, finding evidence that gender and sex were foundations of racial judgment throughout the centuries.

For example, before race meant anything more than a person’s geographic location, European settlers in Virginia made distinctions between English and African women based on the work they did. The work done by African women was considered labor and was taxable by her employer, while work done by English women was considered domestic (and therefore more civilized) and could not be taxed.

“It disadvantaged one group over the other, but it was entirely arbitrary because both groups of women did all kinds of work,” Kitch says. These kinds of distinctions provided a foundation for the belief that Africans were culturally inferior and should be enslaved.

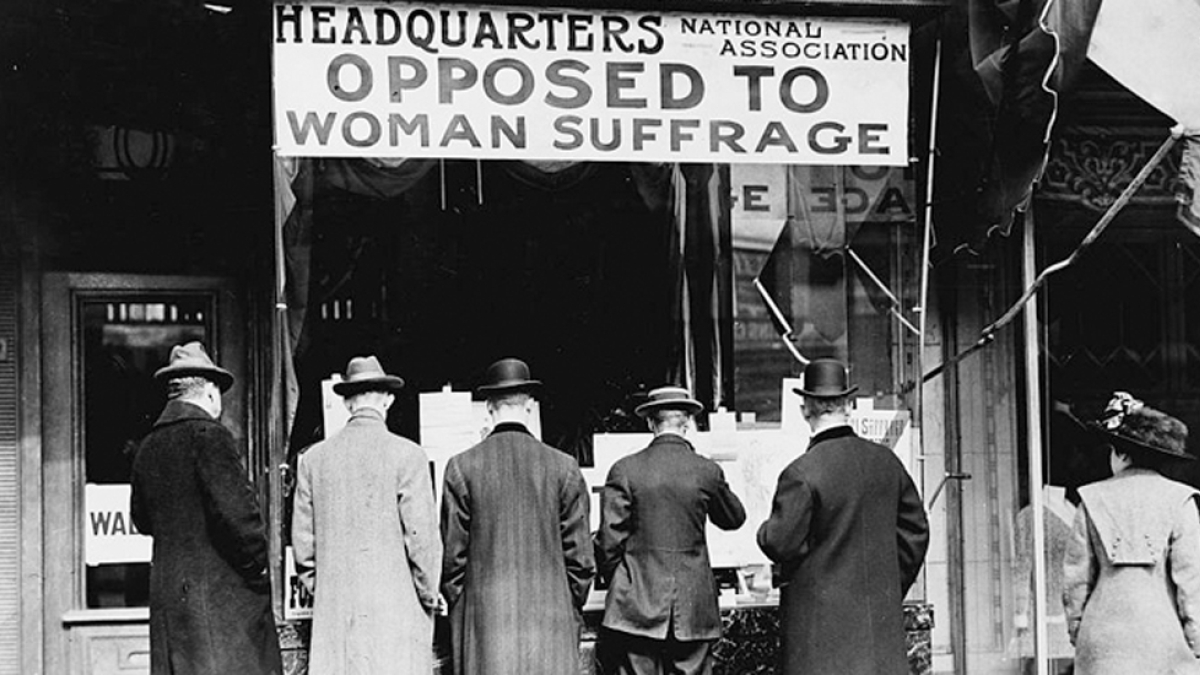

Gender distinctions were also involved in the process of granting U.S. citizenship. While American women achieved the right to vote in 1920, their citizenship was still vested in a father or husband until 1934. Up until then, a woman would lose her citizenship if she married a man from another country.

“If you had offspring outside of the U.S. with a non-American husband, your children wouldn’t have been seen as American because a woman couldn’t transfer her citizenship to her children,” Kitch says.

Perhaps one of the most powerful factors affecting women’s social power and status, however, is their ability to bear children.

“For some reason, societies have decided that there’s something inherently inferior about having a female body and producing offspring,” Kitch says.

Utopian solutions

Throughout history, and especially in the 19th century, the United States witnessed the formation of several “utopian” communities that attempted to overcome gender inequality. Kitch has written three books on the subject of utopianism and gender, including "Higher Ground: From Utopianism to Realism in American Feminist Thought and Theory" (University of Chicago Press, 2000). She wanted to explore whether these communal societies could achieve gender neutrality, and what that would look like.

“What I discovered was that the only communities that managed to achieve gender equity of any kind were celibate societies in which sex and reproduction were just taken out of the equation,” Kitch says.

One such community was the Shakers, a religious group that came to the United States from England. Officially called the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, they advocated for gender equality more than a century-and-a-half before American women were granted the right to vote.

“Reproduction, as these people rightly saw, was a way that women were kept subordinated and kept from achieving other things in their lives. So they would prohibit sex and raise children collectively,” Kitch says. The community often took in orphaned and homeless children in lieu of bearing their own.

Modern challenges

While the Shakers and other experimental utopian communities lost traction over the years, their ideas about women’s freedoms and social status eventually caught on. Today, women vote, own property, have custody rights, and pursue careers. However, holding down a high-powered job usually involves sacrifices to family life.

A recent "State of the World's Mothers" report by the Save the Children foundation found that maternity leave policies in the U.S. are among the least generous in the developed world. Unlike families in other first-world countries such as France, which provides free 24-hour childcare for working parents, Americans receive little support in caring for their children. Because women still shoulder the majority of child-rearing responsibilities, they are most affected by these policies.

“We do see women empowered, but when we start studying who these women are and what their lives have been like, you discover that marriage and family and high-powered careers are still extremely difficult to navigate,” Kitch says.

In addition, political debates over access to family planning services are raising fears that women in the United States may face increased obstacles to balancing work and family. An example of this is the Blunt Amendment, which was narrowly defeated in the U.S. Senate, but would have allowed any employer or health insurance company to deny coverage for contraception.

“We’ve been reminded again recently about how sex and reproduction work in terms of social status in the United States,” Kitch says. “It certainly feels right now like we’re back to the place where some men in power are willing and eager to make decisions about women’s bodies and reproductive rights, without women’s consent or participation. It’s coming out in some pretty aggressive ways.”

Women and Gender Studies is part of the School of Social Transformation, an academic unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

Written by Allie Nicodemo, Office of Knowledge Enterprise Development. This article first appeared on Research Matters.