How a university went into space: ASU's story

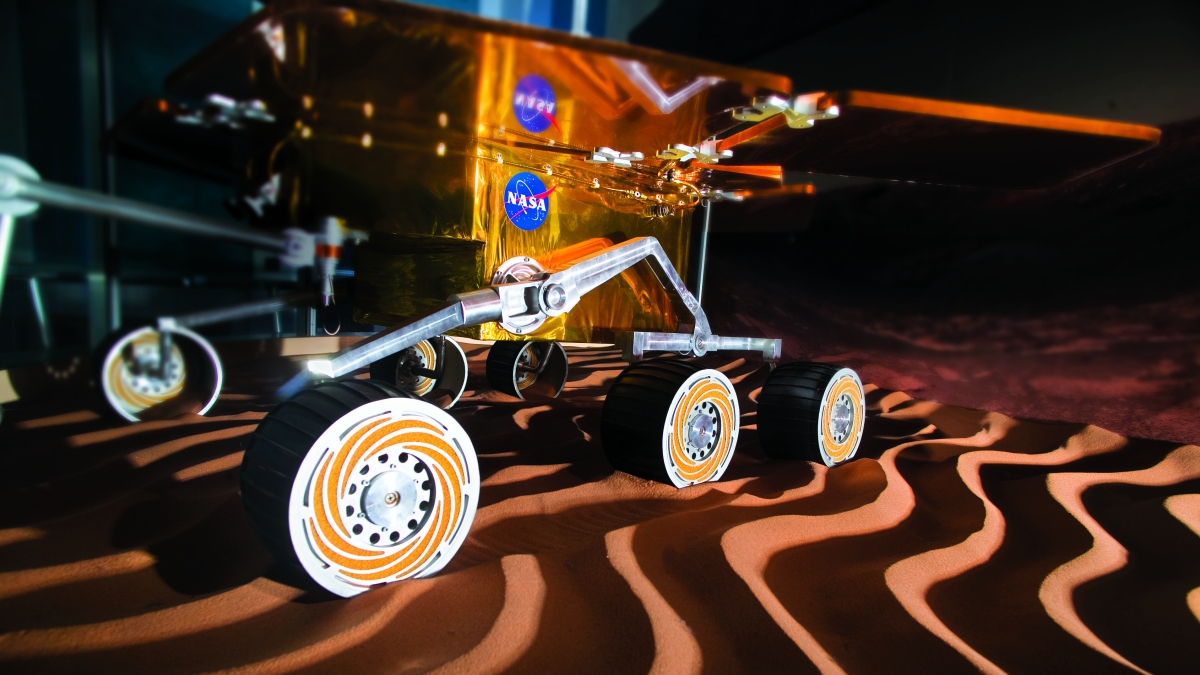

A Mars rover replica at ASU. The university has played roles in 25 missions to eight planets, three asteroids, two moons and the sun.

Editor's note: Read about the future of ASU's space program here.

Only 30 institutions in the United States can build spacecraft. Only seven build interplanetary spacecraft that leave Earth’s orbit.

Arizona State University is one of them.

ASU’s space program is in elite company. And this week’s CubeSat mission announcement adds to the university’s stellar resume: It will be the first time ASU will lead an interplanetary science expedition.

It’s not the university’s first outing by a long shot, however.

ASU has played roles in 25 missions to eight planets, three asteroids, two moons and the sun.

The School of Earth and Space Exploration was created in 2006. As an institution however, ASU’s space program started much longer ago. This is the story of how a traditional geology program merged with the astronomy side of the physics department and grew into a powerhouse that builds spacecraft.

.jpg)

Ron Greeley, hired from NASA in 1977, is widely considered the father of ASU’s space program. An asteroid was named 30785 Greeley in his honor; he died in 2011. Photo by ASU/SESE

ASU's space exploration origins lie in the quest to send men to the moon in the 1960s. Ron Greeley, one of the founders of planetary geology, was working at NASA, helping select landing sites for the Apollo missions and assisting in geologic training for astronauts.

Back in the Apollo days, science was incidental to missions. Engineers – who just wanted to put boots on the moon – frequently clashed with scientists, who wanted to do at least a few things as long as we were going all that way.

One famous story illustrating the rift centered on a geologist who suggested a rock hammer be included in an astronaut’s tool bag. “But we took one of those on the last mission!” an engineer exploded.

Early astronauts tended to be fighter jocks who weren’t much interested in rocks either. Greeley succeeded in educating them to be more sophisticated than simply describing rocks as big or little, and how to differentiate between an interesting rock and a more prosaic sample.

“He was trying to get them to think about the geology and the rocks and what to look for when they got to the moon,” said Phil Christensen, a Regents Professor of geological sciences in ASU's School of Earth and Space Exploration. “If you listen to the transcripts of those astronauts, Ron and others who trained them did a fantastic job. There were a few (astronauts) who were classic test pilots, Navy guys on an adventure and, oh, I picked up a few rocks. Most of them did a good job.”

In 1977, Greeley was hired at ASU and focused his research on data from early robotic NASA missions. He received a number of honors during his career, from an asteroid named for him (30785 Greeley) in 1988 to numerous NASA awards.

.jpg)

When now-Regents' Professor Phil Christensen first won a big contract to build a space instrument, he didn't get the reaction he expected. Photo by ASU/SESE

If Greeley was the father of ASU’s space program, Christensen is the founder of what the program has become.

Back in 1981, Greeley hired Christensen as a young postdoc who was starting to get involved in space missions. Christensen won a big NASA grant to put an instrument on one of the Mars orbiters.

He's since become a Regents Professor (top tenured faculty who have made significant contributions to their field) and is the director of the Mars Space Flight Facility in SESE.

Greeley was a brilliant field geologist and planetary scientist, but he wasn’t an instrument guy, Christensen said.

“Ron was a pioneer in looking at the data that came back from these probes, looking at images of the moon and Mars and analyzing them, thinking about them,” he said. “He had no interest in building the instruments, building the cameras, building the spectrometers. … He was on the team, he had access to the data, he was a leader in the field, but he was mostly looking at data that existed and doing the usual science. That’s what ASU did. They didn’t build anything.”

And when Christensen won a huge contract to build an instrument in the early 1980s, hardly anyone jumped for joy. In fact, the reaction was nervousness and wondering where to put them.

Christensen asked an associate dean for office space.

“He said, “Well, there’s a couple of filing cabinets you can have.’ They just didn’t get it. We had this 10, 20 million dollar contract. It was the biggest contract ASU had ever done. They had no idea how to do it. They had no idea how to deal with an aerospace company. So to go from someone offering me two file cabinets to (the current space program and state-of-the-art facilities) … there’s been a lot of changes at this university. It’s been really amazing to watch this grow.”

.jpg)

Jim Bell has built several cameras currently on Mars or in space. Photo by ASU/SESE

Jim Bell is a professor in SESE, the deputy principal investigator of the LunaH-Map CubeSat mission, and director of the NewSpace Initiative at ASU.

The latter is a program that connects students and faculty doing space-related work with outside entities doing the same thing. They range “from SpaceX to a couple of teenagers in a garage,” Bell said. “Where do they need our help? Can you do a mission for 1 percent of the cost of a big NASA mission?” (They don’t know the answer to that yet.)

Until now, ASU’s space program has revolved around making instruments that are snapped up by NASA. ASU faculty have been involved with all of NASA’s robotic missions.

“NASA knows us scientifically, but also from an engineering standpoint,” said Bell, who has built several cameras currently on Mars or in space.

And that is because of Christensen and Greeley.

“Those two guys were part of the bedrock foundation of the NASA work here at ASU,” Bell said.

In the early 1980s, NASA picked the University of Arizona to run a Mars mission. That university asked Christensen if he could build an instrument for it.

At the same time, defense contractor Raytheon shut down the Santa Barbara facility where Christensen had been working for ASU. Three or four of his colleagues became available. He thought if they came in, and ASU helped out, an instrument could be built at ASU. The instrument they wanted was very similar to one they had already built.

“It was a perfect storm,” Christensen said. “We were one instrument that was part of a bigger project. It wasn’t a huge risk to NASA to pick the UofA to run this mission and one of the instruments will be built at ASU. It was very similar to what we’d built before. … It was fortuitous that everything came together just right.”

They worked their tails off for five years.

“This was a one-shot deal,” Christensen said. “Reputation works both ways. If we screw this up, they’re never going to talk to ASU again. Fifteen people on this project took that really seriously. Not just their careers; ASU had spent a lot of money on this building and these facilities. There was a lot riding on us succeeding. People took a lot of pride in this succeeding. And it did.”

.jpg)

The 300,000-square-foot Interdisciplinary Science & Technology Building IV opened in 2012 on the Tempe campus. It boasts labs, clean rooms, a 250-seat auditorium and one of two mission operations centers on campus. Photo by ASU/SESE

ASU had no place to build instruments or spacecraft when Christensen landed at the university in the early 1980s.

“Now we can build a NASA flight-quality instrument in this building,” he said. “Ten years ago we would have laughed: ‘We can’t do that. We don’t have the facilities, the people, the credibility.’ But we’ve done it. And now because of that, people are coming to me to build them instruments for Europa and other missions. Jim Bell can say we can build and test cameras here. We have new faculty coming in. Ten years from now there will be several people building instruments in this building. ASU will eventually win a Discovery-class mission.”

NASA’s Discovery missions are low-cost missions within the solar system with narrow focus. (Cost is relative in space. Discovery missions still cost what an average person would consider a vast sum, but they’re cheap compared with anything involving people being present.)

“A NASA mission is 90 percent about the process,” Christensen said. “How do you do it? How do you make it work? All things you have to do, all the people working together, keeping them together, keeping them from killing each other – to me that’s half the fun. … Within NASA, like a lot of other places, it’s all about reputation. Can you do it? Once you can, that’s a huge step. Suddenly you’re building more, and people come because of that. It sort of mushrooms.”

From left: Project principal investigator Phil Christensen, senior engineer William O'Donnell and lead engineer Greg Mehall stand in one of the clean rooms with the OSIRIS-REx Thermal Emission Spectrometer on June 22, destined for a 2016 mission to the asteroid Bennu. The clean rooms require hair — including facial hair — be covered. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

And the university’s physical investment in its space program has come a long way from two battered filing cabinets.

The 300,000-square-foot Interdisciplinary Science & Technology Building IV (or ISTB4, in local parlance) opened in 2012. It boasts labs, clean rooms, offices, high bays, a 250-seat auditorium and one of two mission operations centers on campus.

“My colleagues at any other institution come here and they’re jealous,” Christensen said. Last week a Jet Propulsion Lab delegation met with Christensen at the space building. They were jealous, too.

“It takes money to make money,” Christensen said. “You build a facility like this, it pays for itself. NASA does not want you building stuff out of spit and baling wire. When they come here and see this, they say, ‘You guys are for real.’ ”

Incidentally, 40 countries can build spacecraft, but only four can build interplanetary spacecraft. That puts ASU ahead of most countries in that aspect.

The clean rooms in the ASU space building are about the size of a small high school gym.

“That’s where we’ll build the (LunaH-Map) spacecraft,” Bell said.

It has the usual desks, monitors and chairs. What isn’t usual are the two vacuum chambers, one the size of a packing crate and the other about the size of a Volkswagen bus. They’re used to simulate space conditions. The lab team can crank all the oxygen out of the chamber, drop the temperature down to absolute zero (minus 459.67 degrees Fahrenheit), and see how what they’ve built stands up to space conditions.

“You turn it into outer space,” Bell said. “It’s pretty rare for a college campus (to be able to test instruments in that environment). Only a handful of campuses around the country have that capability. Typically you only find that in NASA centers and big aerospace companies.”

The collaborative nature in ASU's space program drew Jekan Thanga, who is the chief engineer of the new CubeSat lunar mission announced this week. Photo by ASU

Space system engineer Jekan Thanga came to ASU two years ago, attracted by the school and the space program. He specializes in robots, artificial evolution, exploration of extreme environments, and CubeSats, the small spacecraft like the one ASU is sending to the moon. (He is the chief engineer on the project.)

The institute’s collaborative nature drew Thanga here. It’s not a conventional aerospace environment. A scientist can walk down the hall, tell an engineer like Thanga he needs to get data from somewhere really nasty and inaccessible, and the engineer can figure out how to make a machine that will go there, survive and get the data home.

“To the engineering world, it’s a radical departure,” Thanga said. “There is determination here.”

.jpg) Thanga and his team spend a lot of time in the clean rooms. They have put machines inside the vacuum chambers, thrown in a bunch of dust and rocks, and cranked them up to see how they fared. (If you were in put it, your eyeballs would pop, the blood in your veins would boil, and eventually you’d boil away. Outer space is a tough place.)

Thanga and his team spend a lot of time in the clean rooms. They have put machines inside the vacuum chambers, thrown in a bunch of dust and rocks, and cranked them up to see how they fared. (If you were in put it, your eyeballs would pop, the blood in your veins would boil, and eventually you’d boil away. Outer space is a tough place.)

It’s not uncommon to come in to the clean rooms at 7 a.m. on a Saturday morning and find grad students working on projects. About 15 to 20 people are working on all aspects of design and development at any given time.

It’s a far cry from the ’60s, when engineers fought scientists. Now they are in the same building (pictured left), unseparated by distance or bureaucratic walls.

“The cutting edge of space exploration is that it’s not good enough to just tell somebody to go build a camera and show up and use it later,” Bell said. “You really have to have your goals in mind while that instrument is on paper. You really have to dive in and become an optics expert. I’ve got to work with optics experts and electrical engineers and all that because I want to make a certain measurement to a certain level of accuracy in a certain environment.

“The more I can partner with people who understand the engineering and the guts of the electronics, the better my experiments will be. Building those people into the department that is my home at the university is just incredibly efficient and wonderful.”

Some 40 years after Greeley’s time, NASA comes to ASU’s door.

“When you do things well – really, really well – people notice,” Christensen said. “It’s not just me. ‘Oh, ASU can build those instruments.’ And that flows over to Jim and Craig (Hardgrove, principal investigator on the lunar CubeSat mission) and Erik (Asphaug, working on how to perform a CAT scan on a comet) and Linda (Elkins-Tanton, school director). We’ve built ASU’s reputation.”

The Mars Rover helped a lot too, he said.

“Being world leaders in something as visible as exploring Mars got a lot of attention to ASU that leveraged a lot of things going on here now,” Christensen said. “A lot of science is fabulous but, I’m sorry, landing on Mars is not the same as discovering a new type of plastic for Coke bottles; OK, great. Landing on Mars gets you on the cover of magazines.”

Coming Thursday: What's next for ASU's School of Earth and Space Exploration.

More Science and technology

Brilliant move: Mathematician’s latest gambit is new chess AI

Benjamin Franklin wrote a book about chess. Napoleon spent his post-Waterloo years in exile playing the game on St. Helena. John…

ASU team studying radiation-resistant stem cells that could protect astronauts in space

It’s 2038.A group of NASA astronauts headed for Mars on a six-month scientific mission carry with them personalized stem cell…

Largest genetic chimpanzee study unveils how they’ve adapted to multiple habitats and disease

Chimpanzees are humans' closest living relatives, sharing about 98% of our DNA. Because of this, scientists can learn more about…