Concert, lecture series to honor Holocaust composers

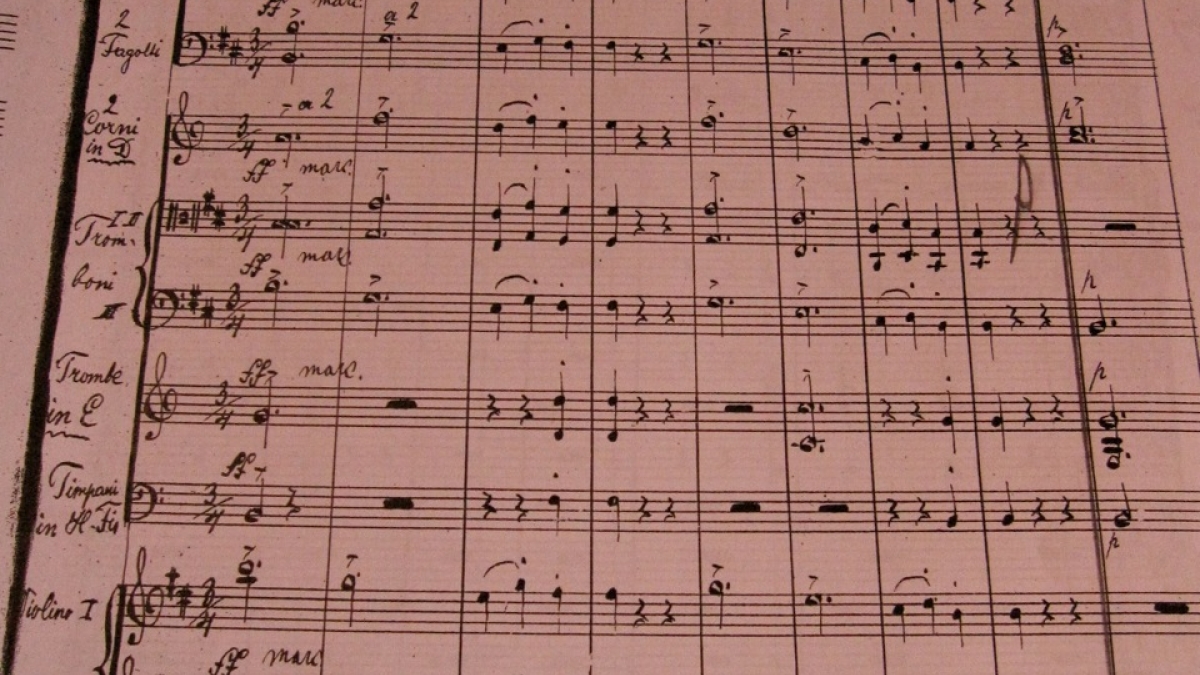

<p> Marcel Tyberg, an Austrian composer who studied at the Vienna Academy of Music, took on the challenge of finishing Schubert’s Symphony No. 8, using notes and sketches the famous composer had left at his death.</p><separator></separator><p> Tyberg did complete the work sometime during the middle of World War II, and if not for a terrible turn of events, Tyberg’s music, and his name, might well have been as famous as that of Schubert.</p><separator></separator><p> But shortly after finishing the composition, which he named his Third Symphony, Tyberg, who was then living in Italy, was arrested by the Nazis and eventually met his end at the notorious Auschwitz death camp.</p><separator></separator><p> Just before he was sent to Auschwitz, Tyberg stuffed his score into a suitcase and gave the case to a friend. Somehow, some way, the suitcase made it to Buffalo, N.Y., where it remained unopened for several decades.</p><separator></separator><p> In another twist of fate, the music made its way to The Phoenix Symphony and became part of an unusual, and moving, series, titled “Rediscovered Masters: A Concert Series Honoring the Music of Jewish Composers Who Were Silenced.” The series, which began in fall 2010 and continues through spring 2011, is co-presented by ASU’s Center for Jewish Studies.</p><separator></separator><p> The series includes lectures, films and numerous concerts by the Phoenix Symphony.</p><separator></separator><p> Hava Tirosh-Samuelson, director of the Center for Jewish Studies in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, and a co-founder of “Rediscovered Masters,” said, “We want to bring this music to the attention of Jews and non-Jews, and to present the music of composers who have been silenced twice – first by death, and then by non-performance of their music.”</p><separator></separator><p> The series began last October with a lecture by Tirosh-Samuelson, “From Mendelssohn to the Holocaust,” and a performance of Hans Krása’s “Brundibár.”</p><separator></separator><p> The next concerts and lecture will be Feb. 2, 3 and 5. David Schildkret, professor of choral music at ASU, will give a free lecture at 7:30 p.m. Feb. 2 at Congregation Beth Israel, 10460 N. 56th St., Scottsdale, titled “Judaism and Christianity: Shared Heritage, Diverse Interpretations.”</p><separator></separator><p> Schildkret will repeat the lecture at 6:30 p.m. Feb. 3 at Symphony Hall, and the Phoenix Symphony will perform Mendelssohn’s “Elijah” at 7:30 p.m. Feb. 3, and again at 8 p.m. Feb. 5.</p><separator></separator><p> At 7:30 p.m. Wednesday, Feb. 16, musicians from the ASU Herberger School of Music and singers from the community will join for a free concert at ASU Gammage titled “Composers in the Concentration Camp,” conducted by renowned maestro Israel Yinon. Yinon has devoted his career to performing and recording the works of Jewish composers.</p><separator></separator><p> As part of the February lineup, the film “Against the Tide” will be shown Feb. 12-28 at various times at Harkins Chandler Crossroads and Camelview theaters. “Against the Tide” is the story of a young activist named Peter Bergson who challenged American Jewish organizations to rescue Europe’s Jews during the Holocaust.</p><separator></separator><p> The idea for “Rediscovered Masters” grew out of a relationship between ASU and the Phoenix Symphony that started several years ago when Tirosh-Samuelson was introduced to Maryellen Gleason, then president of the orchestra, by Robert Tancer, president of Friends of Jewish Studies at ASU.</p><separator></separator><p> “He thought the two of us would hit it off and he was right,” Tirosh-Samuelson said. She invited Gleason to chair a session at a 2010 conference on Felix Mendelssohn at ASU, and then they began discussing the possibility of presenting music by Jewish composers who had been victims of Nazi persecution.</p><separator></separator><p> “The Phoenix Symphony’s was an artistic decision,” Tirosh-Samuelson said. “They wanted to bring the repertoire to the public, so we decided to combine music and academia and present a lecture series.”</p><separator></separator><p> The composers being featured in “Rediscovered Masters” range from those with slim ties to Judaism, such as Tyberg, who was raised a Catholic, to Mieczyslaw Weinberg, whose family was decimated by anti-Semitic violence even before his birth in 1919.</p><separator></separator><p> Their stories are all profoundly tragic. Tyberg’s family was living in Italy when, during a Nazi-mandated census in Italy in 1943, his mother told census-takers that she and her family were racially Jewish because one of her great-grandfathers was a Jew. She was not worried, since the Tybergs had never practiced Judaism and were well-known musicians. But laws were changed and Tyberg was eventually sent to Auschwitz.</p><separator></separator><p> Krása was imprisoned in the Terezin work camp, where he was able to reconstruct his 1942 children’s opera, “Brundibár,” and present it more than 55 times with a full cast of child performers and musicians before he and most of the musicians were taken to Auschwitz and murdered.</p><separator></separator><p> “Art and music were allowed in Terezin – but it was a façade,” said Tirosh-Samuelson. “The music, much of which was saved, turned out to be an unwitting gift of the Nazis.”</p><separator></separator><p> Another of the composers is Erwin Schulhoff, whose Symphony No. 2 was performed in November. Schulhoff composed classical music for radio performance, and was an outspoken Marxist and supporter of the Soviet Union. He applied for citizenship in the Soviet Union, but before he could emigrate, he was arrested by the Nazis and deported to the Wüzberg concentration camp, where he died of tuberculosis in 1942. (His father, also a musician, died the same year in Terezin.)</p><separator></separator><p> Composers to be featuring in the spring are Kurt Weill (“Suite from The Threepenny Opera”) and Pavel Haas (“A Study for Strings”). Weill was born to a religious Jewish family in 1900 and his music was targeted by the Nazis. He moved to the United States in 1935 to escape persecution.</p><separator></separator><p> Haas, born in Czechoslovakia, knew he was going to be a target when Nazis began to focus on his town of Brno. He divorced his wife so she and their young son could escape the Nazis. Haas was soon arrested and sent to Terezin, where he composed music, including “A Study for Strings,” until he was sent to the gas chambers of Auschwitz.</p><separator></separator><p> The series also includes several works by Mendelssohn, who was born into a prominent Jewish family in 1809 but later in his life was baptized a Lutheran. His music was suppressed during the 19th and 20th centuries as a result of anti-Semitism in Europe.</p><separator></separator><p> Michael Christie, the Virginia G. Piper music director of The Phoenix Symphony, who conducts each of the concerts, said he feels “a tremendous sense of responsibility to the memory and legacy of each composer when we perform their music.</p><separator></separator><p> “Since most of the works will be new to our audience, this could be their only experience with these composers. This sense of ‘once in a lifetime’ is taken seriously. I also like the idea of spurring the curiosity of listeners and performers alike.”</p><separator></separator><p> The orchestra members, he added, feel this sense of responsibility, too.</p><separator></separator><p> “I don't think they feel somber as much as serious about the task of bringing these works to life again. I feel like all of us on stage share a great sense of stewardship for these musical colleagues who experienced unspeakable stress, heartache and in some cases, death.”</p><separator></separator><p> Though all the music that the orchestra is playing in this series, with the exception of Tyberg’s Unfinished Symphony, has been published, it is rarely played, if at all, in the United States,” Christie noted.</p><separator></separator><p> “It is quite widely known that incredible amounts of music was suppressed or destroyed during Nazi occupation of Europe. It amazes me however that so many works have either fallen out of general knowledge or haven't been played even if people know that the piece was written. Perhaps there could be a renaissance of certain composers as a result of this series.”</p><separator></separator><p> One of Tirosh-Samuelson’s goals with the project is “to show the depth and the complexity of Jewish culture in the years before the Holocaust, to show how incredible that culture was.”</p><separator></separator><p> Music is a perfect vehicle for entering that world, according to Tirosh-Samuelson. “Music is a cultural agent. There’s something beautiful, compelling and powerful about the music. It’s profound. We read the program notes, but there’s much more to learn.”</p><separator></separator><p> Tirosh-Samuelson said she is not a Holocaust scholar, and that the Holocaust was “not the pivotal point of Jewish history. But it should not be forgotten. By bringing this music we will never forget what happened. There’s a legacy here that can be recovered.</p><separator></separator><p> "Many of the composers were secular Jews who were fully integrated in European society and culture, but they died as Jews and because they were Jewish. They were marked out by a Jewish star and they were gradually removed from society. </p><separator></separator><p> “The existence of Jews today is a testament to the remarkable Jewish power of survival, notwithstanding the attempts to annhilate the Jews.”</p><separator></separator><p> The music that was left behind is also a testament to the human spirit, Tirosh-Samuelson said. “Brutality cannot squelch the human spirit.”</p><separator></separator><p> Tirosh-Samuelson also sees the series as a perfect example of what the university should be doing. “For me, the role of the university is not about producing degrees. The pursuit of knowledge is lifelong,” she said. “There are a lot of intelligent people in our community who are dying to learn. We need to encourage them to read more, learn more.”</p><separator></separator><p> For more information about the series, go to <a href="http://jewishstudies.clas.asu.edu/">http://jewishstudies.clas.asu.edu/<…;